India’s Justice Crisis: Can India’s Democracy Survive Without Judicial Reform?

India’s judiciary is collapsing under delays, inconsistency, and lost trust. We explore why a bold fusion of Civil Law, Common Law, and Dharmic principles is the only path to revive justice—and save India’s democracy from slow decay.

Long ago, in a distant mountain village, there lived a Zen master known for his wisdom. One day, the villagers came troubled.

“Master,” they said, “the village judge is accused of taking bribes. Some say he tilts the scales before hearing a case.”

The master nodded and said nothing. Instead, he asked for the village’s old weighing scale—the one used for generations by traders to measure rice.

When they brought it, he placed a stone on one side. “If this scale is even slightly tilted, every trade is unfair. Over time, the village loses trust—not just in the scale, but in every merchant, in every measure, in every deal.”

He continued, “A judge is the scale of society. If people lose faith that the scale is fair, then no verdict holds weight. Contracts become paper, promises become noise, and peace becomes impossible.”

The villagers asked, “But what if only a few know the scale is crooked?”

The master smiled, “Soon, all will know. And when they do, even the innocent will be weighed with suspicion. Then, society itself crumbles—not by war or famine, but by the quiet rot of lost trust.”

SUPPORT DRISHTIKONE

In an increasingly complex and shifting world, thoughtful analysis is rare and essential. At Drishtikone, we dedicate hundreds of dollars and hours each month to producing deep, independent insights on geopolitics, culture, and global trends. Our work is rigorous, fearless, and free from advertising and external influence, sustained solely by the support of readers like you. For over two decades, Drishtikone has remained a one-person labor of commitment: no staff, no corporate funding — just a deep belief in the importance of perspective, truth, and analysis. If our work helps you better understand the forces shaping our world, we invite you to support it with your contribution by subscribing to the paid version or a one-time gift. Your support directly fuels independent thinking. To contribute, choose the USD equivalent amount you are comfortable with in your own currency. You can head to the Contribute page and use Stripe or PayPal to make a contribution.

The Corrupt Judge

A Delhi High Court judge, Justice Yashwant Varma, was found with proceeds of corruption. During his tenure at the Delhi High Court, a large sum of cash was discovered at his residence, prompting an in-house inquiry by the Supreme Court. The investigation found him guilty of having cash. But there was no guilty verdict or punishment. Instead, he was transferred to the Allahabad High Court in April 2025.

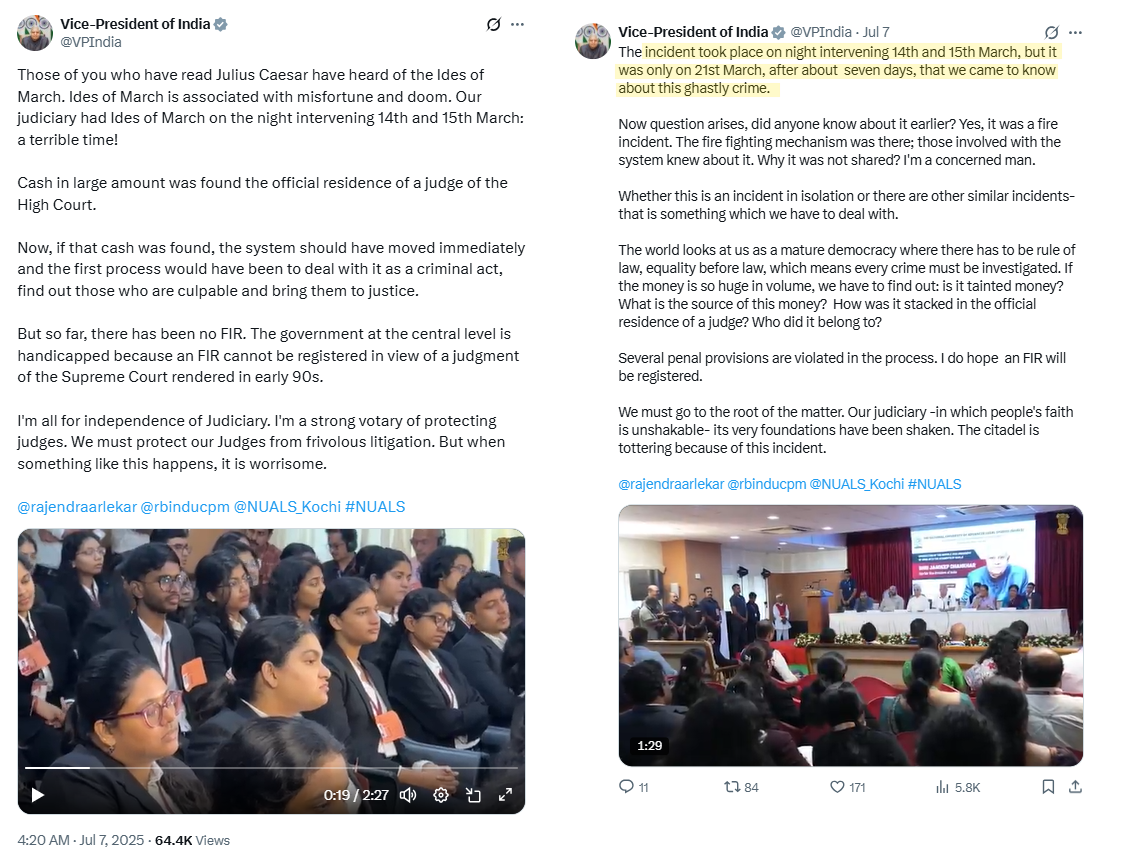

You can watch the video where India's VP, Mr Jagdeep Dhankar, shares his anguish at the incident where a Delhi High Court judge, Justice Yashwant Varma, was caught with cash in his residence.

In a series of posts on X, he shared the context.

When the Vice President of India, Jagdeep Dhankhar, raises alarm over the patronage and post-retirement culture among judges, it should not be dismissed as mere political commentary. It is a searing indictment of a judiciary.

A judiciary that, on the one hand, aims to encroach upon the powers of the executive and unilaterally, without mandate create social change that has deep ramifications. And, on the other hand, it risks becoming a stooge of the executive via post-retirement posts.

India’s Constitution did not impose restrictions on post-retirement employment for judges because the framers believed in judicial morality. Judges, it was presumed, would retreat into dignified retirement, untainted by political favors. But today, the judiciary's retirement pipeline flows directly into gubernatorial chairs, tribunals, and commissions.

Not every judge secures such sinecures — only the pliant or politically useful ones are rewarded. As Vice President Dhankhar rightly noted, this pick-and-choose culture breeds patronage, fatally wounding judicial independence.

Such is India's predicament now.

We discussed the corruption of Justice Yashwant Varma. But this is not new.

Case Study: The Shielding of Corrupt Judges in India

Consider the infamous case of Justice Narayan Shukla of the Allahabad High Court, who was caught in a corruption scandal involving medical college admissions. An internal Supreme Court inquiry found him guilty of judicial misconduct.

Chief Justice of India (CJI) Dipak Misra on Tuesday recommended the impeachment of Justice Shri Narayan Shukla, the eighth senior-most judge of the Allahabad High Court, following an adverse report about him by an in-house panel set up by the CJI. The CJI has set the process in motion with a letter to the Prime Minister for the impeachment of the judge. When the impeachment motion is moved in Parliament, an investigation is conducted. If the findings of guilt are confirmed, the impeachment motion will be put to vote for the removal of the judge by a majority. (Source: Allahabad High Court judge Shri Narayan Shukla to be impeached / The Hindu)

Yet, no impeachment followed. Instead, the government sat on the file. Justice Shukla quietly retired with his full entitlements. This shielding of corrupt judges by both judiciary and executive sends a chilling message: the higher judiciary polices its own with indulgence, not rigor.

Similarly, in 2019, there were allegations against a former Chief Justice of India involving sexual harassment. Instead of a transparent, independent inquiry, the Supreme Court constituted an in-house committee comprising its own judges, which unsurprisingly gave a clean chit. This process was opaque, lacked independent oversight, and further eroded public trust.

International Contrast - How Other Democracies Handle Judicial Corruption and Misconduct

In stark contrast, Western democracies treat judicial misconduct as a mortal threat to the republic.

- United States: When federal judges face allegations of corruption, Congress can initiate impeachment proceedings, as it did with Judge Thomas Porteous in 2010 for corruption and perjury. He was swiftly removed by the Senate. Moreover, the Judicial Conduct and Disability Act empowers oversight panels to investigate complaints against judges.

The Senate on Wednesday found Judge G. Thomas Porteous Jr. of Federal District Court in Louisiana guilty on four articles of impeachment and removed him from the bench, the first time the Senate has ousted a federal judge in more than two decades. Judge Porteous, the eighth federal judge to be removed from office in this manner, was impeached by the House in March on four articles stemming from charges that he received cash and favors from lawyers who had dealings in his court, used a false name to elude creditors and intentionally misled the Senate during his confirmation proceedings. The behavior amounted to a “pattern of conduct incompatible with the trust and confidence placed in him,” according to the articles against him. (Source: Judge Thomas Porteous Removed by Senate After Impeachment / New York Times)

- United Kingdom: Judicial conduct is scrutinized by the Judicial Conduct Investigations Office (JCIO), an independent body. When Judge Peter Herbert made racially biased remarks in 2015, JCIO investigated and reprimanded him, reinforcing that judges are not immune from ethical scrutiny.

- Europe: The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) and national judicial councils enforce strict codes of conduct. For instance, Romanian anti-corruption efforts have seen sitting judges prosecuted and jailed for accepting bribes.

These systems are rooted in one principle: no judge is above accountability. The absence of this principle in India — where errant judges retire with honor instead of ignominy — is a rot that will eventually hollow the institution.

The CBI and the Question of Executive Oversight

Vice President Dhankhar's critique of the Chief Justice’s participation in appointing the CBI Director is an extension of his concern for constitutional propriety. While the judiciary’s involvement was designed to depoliticize appointments, it risks drawing the judiciary into executive power plays.

In countries like the United States, the FBI Director is appointed by the President, confirmed by the Senate — ensuring democratic oversight without judicial entanglement. The UK’s MI5 head is appointed purely by the Home Secretary, again maintaining executive autonomy with parliamentary scrutiny.

India’s mixed model creates murky waters where judges influence executive appointments, while executives influence judicial elevations via the opaque collegium system. This blurring of boundaries, as VP Dhankhar warned, threatens the delicate constitutional balance of power.

The Slow Death of Judicial Integrity

If large number of Indian households are impacted by 52 million pending cases, how can justice remain a theoretical virtue when judicial credibility crumbles? The moral authority of the judiciary is its final currency. Post-retirement postings, patronage, protection of corrupt judges, and executive interference are not mere aberrations — they are systemic cancers.

This song clearly exemplifies the mood of the common man.

The problem with the Indian judiciary are manifold.

Discrimination by the Indian Judiciary is Rampant!

Integrity and Trust is one area. Even its fairness and impartiality is at stake in the way it discriminates between communities. Hindus continue to get the short end of the stick when their cases show up in the courts.

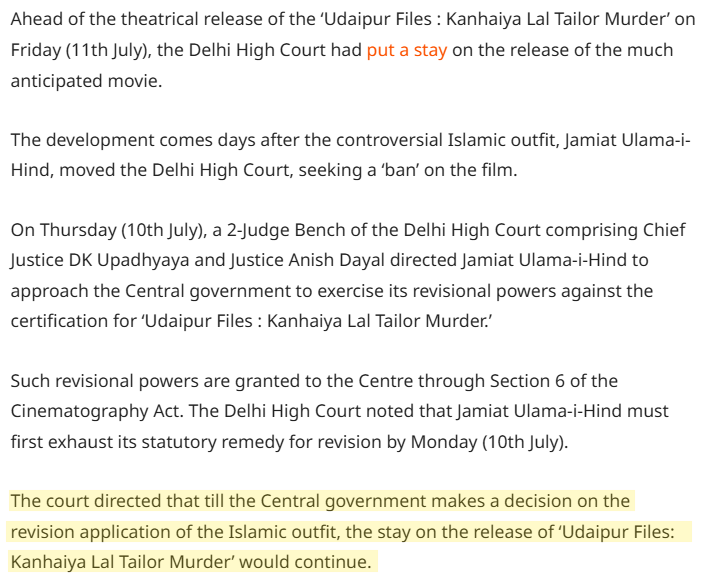

The Indian judiciary is today a tarnished edifice—its actions no longer even pretending to conceal a deep-rooted bias against any narratives that expose the brutalization of Hindus. The ban on 'The Udaipur Files' by the Delhi High Court is yet another exhibit in this hall of disgrace.

One of the actual murderers, Javed, approached the Supreme Court pleading that the film could prejudice his trial. Absurd as it was, the Court did not entertain him—but when the matter landed in the Delhi High Court, the ban hammer fell. The reasoning?

The filmmaker hadn't exhausted all procedural revisions via the Cinematograph Act. There was no concern for truth, evidence, or the social need to document terror. Instead, the judiciary shielded the sentiments of the murderers over the rights of Hindus to narrate their pain.

A Judiciary That Won't See, Won't Hear, Won't Speak

Shockingly, the judge refused to even view the film before banning it.

In contrast, courts in the US and UK follow strict standards to protect artistic and journalistic freedom:

- In the United States, films like The Path to 9/11 or United 93 that dramatized sensitive terror events were released without judicial meddling, despite public outcry.

- In the UK, the BBC has aired highly critical documentaries on British involvement in colonial genocides—yet courts never banned them for fear of "hurting sentiments."

If judicial overreach, like India's, were to occur in these nations, it would spark a massive legal and civil backlash. Freedom of speech is not subject to the sensitivities of criminals or political patrons.

A System Weaponized Against Hindus

But in India, the judiciary becomes supremely alert only when Hindu pain is narrated. Films like Kashmir Files, Kerala Story, Sabarmati Report, and now Udaipur Files face bans, cuts, and threats. Yet, when the BBC releases 'India: The Modi Question', built on hearsay and designed to malign India's PM, no courts intervene. The yardstick is clear: defame Hindus or the Indian state—allowed; expose Islamist violence—banned.

Worse, the courts and institutions like CBFC demand 55+ cuts on films showing Islamic terror, while the same courts instructed "don’t like, don’t watch" for PK, a film that mocked Hindu deities. Why the double standards?

Judicial Complicity Breeds Radical Entitlement

This hypocrisy isn't merely a moral failing. It can destroy the very fabric of the nation.

Shielding radical ideologies under the garb of secularism emboldens terrorists and their handlers. The Jamait Ulema-e-Hind, an organization with a documented history of defending terrorists, openly objected to Udaipur Files. They had earlier funded legal defenses for Al-Qaeda operatives and bomb blast accused, and yet, the judiciary takes their petitions seriously.

A judiciary that curtails the documentation of Hindu suffering but allows the defense of radical Islamists is no longer neutral. It is complicit.

By censoring films that document anti-Hindu violence, the judiciary is writing a blank cheque to Islamist terror: kill, brutalize, silence—because the courts will ensure your victims are never heard. This is not justice; it is perfidy.

In any true democracy, the courts are the last refuge of truth. In India today, the judiciary has become the first wall of obstruction against the Hindu voice.

The rot of anti-Hindu strain within the judiciary runs very deep.

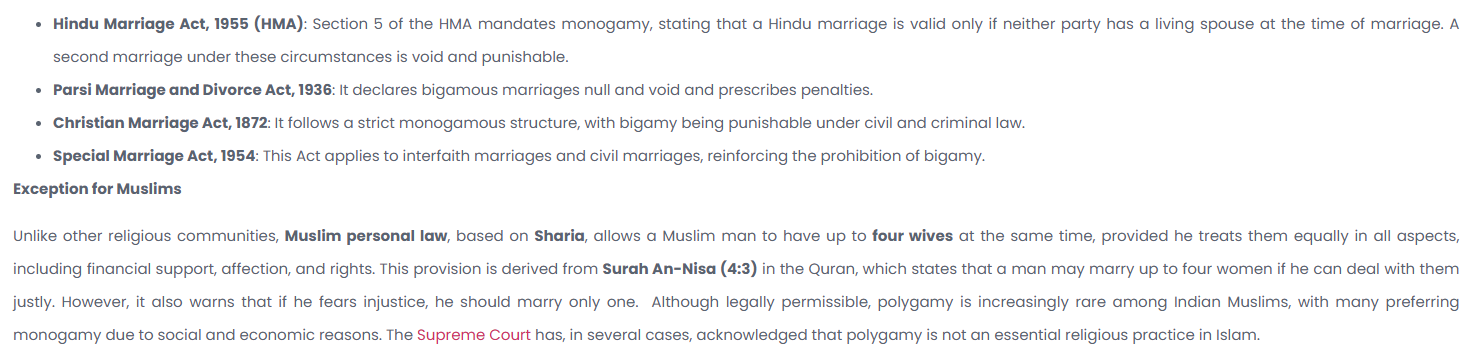

1. Bigamy Laws and Personal Law Exceptions

Hindus, Christians, Parsis, and others: Bigamy is a criminal offense under Section 494 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) and is explicitly prohibited by the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, the Christian Marriage Act, and the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act. Violation can result in imprisonment of up to seven years

Muslims: Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act, 1937, permits Muslim men to have up to four wives, provided certain conditions are met. This exception is not available to any other community, resulting in a legal double standard.

2. Communal Violence Bill, 2011

The draft Prevention of Communal and Targeted Violence (Access to Justice and Reparations) Bill, 2011, sought to define "groups" as religious or linguistic minorities, or Scheduled Castes/Scheduled Tribes. The "majority" (primarily Hindus) could be presumed perpetrators, while only minorities and SC/STs could be recognized as victims.

This bill would institutionalize the presumption that Hindus are always the aggressors, even in regions where they are a minority (e.g., Kashmir, Punjab, Kerala)

The bill was widely criticized for its anti-Hindu bias and was eventually shelved, but its drafting clearly shared how legislative discrimination has been practiced during the Congress and UPA days.

3. Inheritance and Succession Laws

Hindus: Governed by the Hindu Succession Act, 1956, which has been amended to provide equal inheritance rights to daughters.

Muslims: Governed by uncodified Muslim Personal Law, which restricts women's inheritance rights. For example, daughters inherit less than sons, and if there are only daughters, other male relatives (e.g., brothers of the deceased) may also inherit a share.

Judicial Approach: While the Supreme Court has struck down practices like triple talaq, it has yet to address the core issues of gender equality in Muslim inheritance laws, despite constitutional guarantees of equality

The lack of uniformity in personal laws is seen as perpetuating inequality, with reform efforts focused disproportionately on Hindu practices.

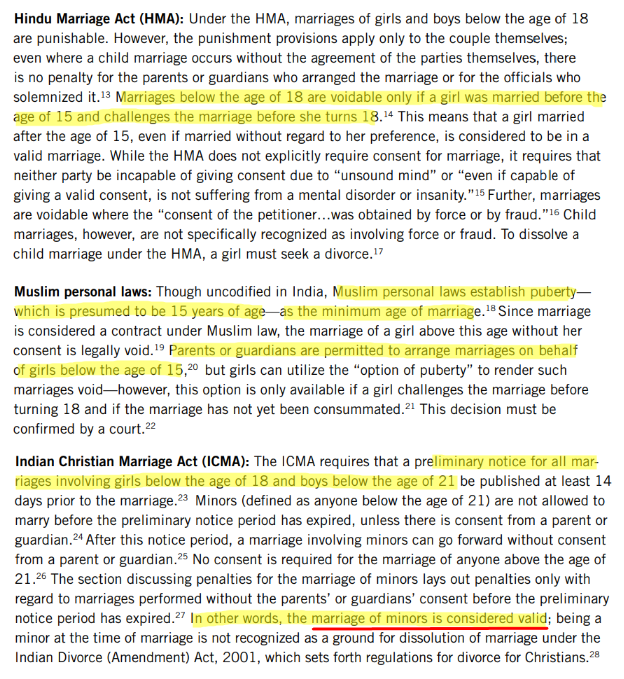

4. Child Marriage Laws

Prohibition of Child Marriage Act (PCMA), 2006: Sets the minimum marriage age at 18 for women and 21 for men. Child marriages are voidable, and penalties are prescribed for those facilitating such marriages.

Muslim Personal Law: Recognizes puberty (presumed at 15) as the minimum age for marriage. Courts have upheld the validity of marriages for Muslim girls above this age, even if below 18, provided they consent.

Judicial Precedent: There have been cases where courts have upheld the marriage of pubescent Muslim girls, citing personal law exceptions, which would be illegal under the PCMA for Hindus and others

This creates a legal loophole, effectively exempting Muslims from the stricter child marriage prohibitions applicable to Hindus and others.

5. Judicial Trends and Perceived Bias

Hate Speech and Freedom of Expression: There are claims that the judiciary is more lenient towards hate speech by non-Hindus but acts swiftly against Hindus accused of similar offenses.

Selective Cognizance: The judiciary is perceived to take suo motu action in cases where minorities are victims but is less responsive when Hindus are targeted, as in the case of the exodus and violence against Kashmiri Hindus.

Case Examples: The arrest and release patterns in high-profile cases, and judicial comments in cases involving communal violence or hate speech, are cited as evidence of differential treatment

The lesser said about the Indian judiciary’s Hinduphobia (Hindudvesh) the better it would be. When it comes to Hindus, the judiciary never tires to show its Hinduphobic side. Their different yardsticks for Nupur Sharma and Samajwadi Party’s Swami Prasad Maurya when it comes to Freedom of Speech is a case in point. In January last year, the Supreme Court (SC) stayed proceedings against Swami Prasad Maurya in the Ramcharitmanas case. While providing relief to the Samajwadi leader, the apex court showed disregard for Hindu religious beliefs, which has come to characterise a large section of the Indian judiciary. (Source: Shockingly 9 out 10 times Indian judiciary places wokeness & political correctness above national security! / HinduPost)

The cases where lawyers of a certain ideology have forced the courts - even the Supreme Court - to open at odd hours, including midnight, are well known. This facility and privilege are not extended to cases involving Hindu rights.

The article recounts the dramatic late-night Supreme Court hearing on July 29, 2015, to prevent the execution of Yakub Memon, convicted for his role in the 1993 Mumbai blasts. Memon’s lawyers sought an urgent hearing to stay the death penalty, arguing procedural lapses and insufficient notice before execution. The three-judge bench, led by Justice Dipak Misra, heard arguments past midnight but ultimately rejected the plea, clearing the way for Memon’s hanging at dawn. The hearing, unprecedented for its timing and urgency, highlighted debates around the death penalty, legal procedure, and justice. The case remains significant for its legal, political, and emotional ramifications in India’s fight against terrorism. (Source: Revisiting a late-night hearing to save Memon from hanging / Hindustan Times)

6. Other Relevant Laws and Issues

- Temple Administration: Many Hindu temples are under direct government control, with state-appointed boards managing their finances and administration. In contrast, mosques and churches are largely managed by their respective communities, leading to accusations of state interference in Hindu religious affairs.

- Religious Conversions: Anti-conversion laws in several states are often enforced in a manner that disproportionately scrutinizes and restricts Hindu organizations, while conversions out of Hinduism receive less legal attention.

The persistent judicial delays in resolving critical Hindu temple disputes — such as the Kashi Vishwanath-Gyanvapi Mosque, Krishna Janmabhoomi-Shahi Idgah, and the Bhojshala Temple in Dhar — expose a systemic bias embedded within India’s judiciary. While cases involving minorities or politically sensitive issues often witness extraordinary urgency, Hindu concerns regarding desecrated temples face endless adjournments, bureaucratic hurdles, and judicial apathy.

Consider the alacrity shown in late-night hearings for convicted terrorists like Yakub Memon, or urgent interventions in cases involving minority or activist causes. Yet, petitions for Hindu civilizational and religious rights languish in courts for decades. The judiciary’s reluctance to address the historic wrongs inflicted upon Hindu temples under Islamic invasions and colonial interventions reflects a deep-seated ideological hesitation. This judicial indifference amounts to discrimination against Hindus, denying them timely justice for reclaiming sacred spaces integral to their identity.

Further, the Places of Worship Act 1991 — enforced rigidly against Hindus — prevents rightful legal reclamation of temple lands, effectively freezing injustices of the past while shielding illegal structures. The judiciary’s silence on the constitutional review of this Act itself is telling.

The Indian legal framework, while secular in its constitutional vision, contains several provisions and practices that result in differential treatment for Hindus compared to other communities. These include exceptions in personal laws (e.g., marriage, inheritance), legislative drafts like the Communal Violence Bill, and judicial trends that appear to apply different standards based on religious identity. While some of these disparities arise from the complexities of managing a multi-religious society with diverse personal laws, the resulting asymmetry has fueled perceptions — and in many cases, realities — of discrimination against Hindus.

In essence, Hindus are denied the urgency, respect, and consideration routinely afforded to others. Justice delayed is not just justice denied—it is civilizational erasure by stealth. Unless this disparity is addressed, Hindus will continue to face a legal system that selectively deafens itself to their historical, cultural, and religious grievances.

Indian Citizen to Judiciary: What's In It For Me?

Rampant and in-your-face prejudice against the Hindu community is now an unfortunate characteristic of the Indian courts. However, what is most interesting is that people have little respect and trust for the judiciary because it does not deliver much to them. It, however, enjoys a lifestyle funded by taxpayers' money.

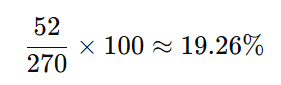

Let us perform a quick calculation on how the Indian courts affect the general public.

In 2023, let us assume that only ~2.3% of individuals were living in extreme poverty, likely well under 10% of households are below it—i.e., over 90% of households are above the extreme poverty line.

With ~270 million households total, that means over 240 million households now fall above the extreme poverty threshold. Let us assume that those under the poverty line would not have any court case against them.

The most recent aggregated data indicates that India currently has over 52 million court cases pending across all levels of the judiciary:

- Supreme Court: ~82,000 cases pending (April 2025)

- High Courts: ~6.2 million cases pending

- District & Subordinate Courts: ~45 million cases pending

Combined, this exceeds 52 million pending cases nationwide.

So let's do a little math.

- 52 million pending cases

- If each case involves one household, then roughly 20% households in India are impacted directly.

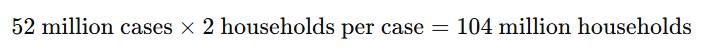

- If each case involves two households, then:

Given India's ~270 million households, the proportion is:

Roughly 40% households in India could be impacted by pending court cases.

And even with the two households per case for the over 52 million cases, we are being very conservative!

It is criminal negligence on the part of the establishment to think that Judicial delays are mere inconveniences. They are not!

In fact, they are fractures in the nation’s constitutional spine.

Land disputes, family feuds, criminal trials — all frozen in a Kafkaesque maze. While the system creaks under corruption and delays, a massive chunk of India’s population remains chained to courtrooms instead of building futures.

Land ownership hangs in limbo, unresolved disputes tear families, businesses stall over breached contracts, and justice for crimes becomes a fading illusion.

Worse, the rot runs deep: over 180,000 cases have languished for more than 30 years. Thirty years of lives wasted in dusty files and courtroom summons.

This backlog chokes not just the courts but the very arteries of development.

We are staring at a complete social decay masquerading as law.

So what can India do?

Let us go back to the original state when the founding fathers of the Indian judiciary were selecting the legal framework.

Did they make a mistake then?

Common Law vs Civil Law

There are two frameworks of law - the Common Law (UK, US, India) and the Civil law (Europe, Japan, Singapore - hybrid).

Common Law (British Origin – including India)

It is dependent on the fact that Judicial precedent shapes law.

Let's examine its strengths and weaknesses.

- Strengths:

- Flexibility: Judges adapt law to new situations via case law.

- Evolutionary: Judicial activism can address contemporary concerns.

- Weaknesses:

- Discretionary interpretations often lead to inconsistent, biased judgments.

- Reliance on lengthy court arguments and procedural delays causes massive backlogs.

- Judges gain disproportionate power to shape law, leading to ideological or political capture—as seen in India's higher judiciary today.

Civil Law

- Strengths:Clear codes leave little room for subjective interpretation.Faster judgments: Judges apply law directly without debating precedents, reducing litigation cycles.Greater consistency and predictability of outcomes.

- Weaknesses:Less flexible to adapt to rapidly evolving societal changes.Judges play a passive role—risks rigidity when legal codes become outdated.

- Examples:Japan: Following the Meiji Restoration, Japan adopted a Civil Law system based on the German model, leading to structured, efficient courts.Singapore: Retains Common Law, but is infused with strict legal codifications and efficient procedural laws, ensuring swifter justice and minimal interference.

For India’s challenges—delays, lack of trust, discriminatory judgments—the Civil Law approach can:

- Limit judicial activism and ideological bias.

- Accelerate case resolutions via strict adherence to codified laws.

- Ensure consistent treatment across cases to reduce the perception of discrimination.

However, India can hybridize: retain common law where flexibility is needed, but introduce comprehensive civil codes with strict procedural enforcement for criminal, commercial, and civil disputes.

But to suggest anything to the Indian judiciary is a suicidal act!

Dharmic Jurisprudence bedrock

However, as we discuss the various frameworks of jurisprudence, it might be interesting to introduce the Hindu or Dharmic framework for jurisprudence.

The fundamental scriptures for determining the Hindu Jurisprudence are:

- Manusmriti (Laws of Manu)

- Yajnavalkya Smriti

- Narada Smriti

- Kautilya’s Arthashastra

- Mitakshara and Dayabhaga Commentaries (on Hindu law of inheritance)

The key takeaways are:

- Dharma: The principle of cosmic and social order—not just legal compliance but ethical righteousness.

- Nyaya: Justice linked to truth and societal welfare, not just procedural technicalities.

- Judges (Kavis) were meant to mediate, not merely adjudicate, resolving disputes based on context, customs, and dharma, ensuring moral justice, not legalistic pedantry.

So what framework should India follow?

Well, let us discuss how India needs to transform its judiciary.

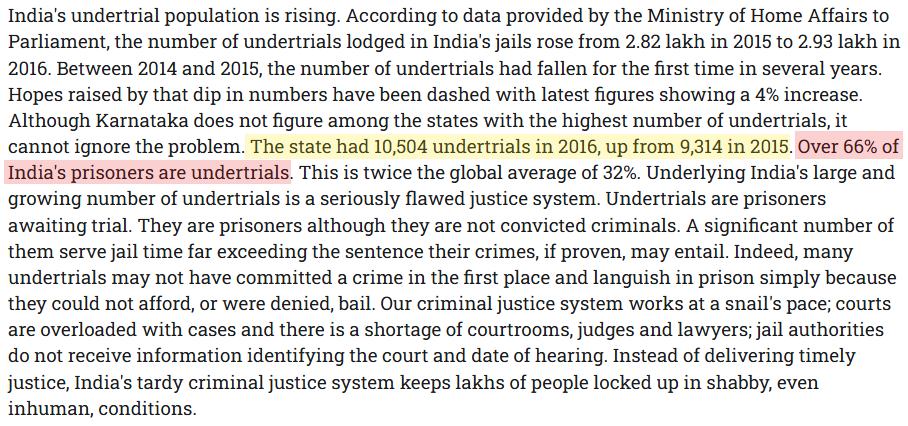

A Hybrid Model?

We argue that India must urgently hybrid judicial reform legal system from inefficiency, bias, and public distrust.

- The first and foremost step is to comprehensively codify all laws—civil, criminal, commercial, and constitutional—thereby minimizing the scope for arbitrary judicial interpretation. By binding judges to clear, structured codes, we reduce the playground for ideological activism and personal biases that have marred the credibility of the courts.

- Secondly, India must integrate Dharmic principles of justice into the legal fabric. Dharma-based justice emphasizes ethical fairness, contextual truth, and social harmony—a stark contrast to the sterile application of black-letter law. This would ensure that judgments uphold not just legality, but righteousness and moral clarity, restoring faith in the judiciary.

- Finally, India needs to streamline judicial procedures following European Civil Law models. Time-bound resolutions, digital case tracking, and specialized fast-track courts must be institutionalized to tackle the crushing backlog of over 52 million cases. Civil Law’s procedural rigidity, combined with Dharmic ethical grounding and the Common Law’s adaptability, can rejuvenate India’s justice system, making it swift, fair, and worthy of a civilizational republic.

Judicial reform is not a choice—it is an existential necessity for India’s democracy. The judiciary’s credibility is eroding under the weight of endless delays, inconsistent verdicts, and opaque processes. To revive trust and ensure justice, India must engineer a comprehensive transformation. This involves synthesizing three core traditions: the clarity and codification of European Civil Law, the flexibility and case-driven adaptability of British Common Law, and the ethical compass of Dharmic jurisprudence, which places Dharma—righteousness and balance—at the heart of justice.

Such a hybrid framework would remove ambiguities in the law, minimize excessive judicial interpretation, and restore predictability in judgments. Simultaneously, it would allow the courts to adapt to new challenges while grounding every decision in civilizational values that prioritize ethical outcomes over mere technicalities. Procedures must be streamlined, backlogs eliminated, and accountability reinforced at every level. The ultimate goal is a system where the ordinary Indian finds justice accessible, swift, and fair—not a privilege for the wealthy or the connected.

Comments ()