Putin - Villain or Visionary? The Untold Story of Russia.

While the West cries villain, Putin rebuilt Russia from ruins — restoring pride, power, and prosperity. As vultures circle, demanding the gates be torn down, the silent gardener stands firm, knowing they seek not just fruit, but the soil and roots of Russia itself.

In a forgotten village on the edge of a barren wasteland stood a broken garden — once vibrant, now reduced to dust and dead roots. The villagers remembered a time when flowers bloomed and trees stood tall, but wars, greed, and betrayal had left it in ruins. The people despaired, and vultures circled high above, waiting to feast on the last remnants of life.

One morning, a silent, stern gardener arrived. He spoke little but worked with relentless precision. He cleared the debris, pruned the dead branches, and fortified the walls of the garden, stone by stone. Some villagers watched with suspicion — his methods were harsh, his tools sharp, and his discipline unforgiving. They whispered among themselves, calling him a tyrant of the soil.

Yet, as seasons passed, the garden began to breathe again. Green shoots pierced through the cracked earth. Trees stood once more with their roots deep and their trunks unyielding. Water flowed where dust had ruled. The villagers now had shade, fruit, and flowers. Still, the gardener remained silent, tending to his work without praise or complaint.

But the vultures grew restless. Seeing the garden flourish, they shrieked from the skies, calling the gardener a villain, accusing him of cruelty and oppression. They demanded that the walls be torn down, that the tools be thrown away, and that the soil be shared freely — so that the vultures too could feast.

One brave child asked the gardener,

“Master, why do you not defend yourself? They call you evil, yet your hands have saved us.”

The gardener smiled gently and said,

“A tree does not argue with the wind. It roots deeper. If I stop now, these vultures will not just eat the fruits — they will tear the roots, steal the soil, and leave only bones. My task is not to argue. My task is to protect what can live.”

The child understood.

And so the gardener worked on, as the vultures screamed louder, circling — yet never daring to land within the walls of a garden now too strong to fall.

SUPPORT DRISHTIKONE

In an increasingly complex and shifting world, thoughtful analysis is rare and essential. At Drishtikone, we dedicate hundreds of dollars and hours each month to producing deep, independent insights on geopolitics, culture, and global trends. Our work is rigorous, fearless, and free from advertising and external influence, sustained solely by the support of readers like you. For over two decades, Drishtikone has remained a one-person labor of commitment: no staff, no corporate funding — just a deep belief in the importance of perspective, truth, and analysis. If our work helps you better understand the forces shaping our world, we invite you to support it with your contribution by subscribing to the paid version or a one-time gift. Your support directly fuels independent thinking. To contribute, choose the USD equivalent amount you are comfortable with in your own currency. You can head to the Contribute page and use Stripe or PayPal to make a contribution.

A Power on Its Knees

When the Soviet Union fell in December 1991, there was unprecedented chaos in Russia and the ex-Soviet republics. Suddenly, it had to transition from a Communist model to a market-based one.

Gregory Clark, a professor at Tama University in Japan, wrote this account of how the collapse played out on the streets. Squalor, theft, opportunism, poverty, and hunger came to define Russian life.

THE FIRST thing that strikes you about the new Russia are the beggars and the street peddlers, thousands of them lined up shoulder-to-shoulder selling off small items of value-a pair of earrings, a carton of milk, some tools and spare-parts that almost certainly have been pilfered from somewhere. Then there is the squalor. Moscow never was a prima donna city. But today it looks like Leningrad after the Nazi siege of 1941/42. Lack of maintenance is endemic. Parts of central Moscow look as if they have been bombed, with whole blocks decaying and abandoned. Road and pipe repairs consist mainly of large craters surrounded by minimal activity. Broken-down, cannibalised cars litter the streets. The place seems to be falling apart. True, not everything is in decline. Coming back for the first time since the Khrushchev era I am delighted by the absence of the KGB spooks and thugs. Once they used to follow you in squads-three to four cars in rotation, with up to three operatives in each car. At the entrance to the Australian embassy the militia still stand guard. But their main job now is to control the crowds trying to get visas for Australia, rather than track your movements in the hope of staging an operation against you later. (Source: "BETRAYED AGAIN – The Failure of the New Russian Revolution" / Gregory Clark)

Communism offers a mechanism of hiding the inconvenient behind an opaque velvet curtain. Nobody knows the truth because the illusion is a grand one.

Whatever numbers and metrics we have from that era cannot be trusted.

In the Soviet Union, the economy was dominated by an intricate web of state-owned enterprises (SOEs), each linked through a centrally planned system that dictated who produced what, in what quantity, and for whom. Unlike capitalist markets, where prices, bids, and competition regulate the flow of goods and services, the Soviet economy operated under administrative command mechanisms devoid of market signals.

At every stage of production—from raw materials to final goods—enterprises fulfilled production quotas rather than responding to consumer demand or profit incentives. Inputs such as steel, coal, or machinery were not "purchased" in a market sense but instead allocated by the State Planning Committee (Gosplan). Money transferred between SOEs was essentially a notional accounting tool, moving through state-controlled banks, without reflecting any true price discovery.

For example, if a steel plant produced 1 million tons of steel, that steel would be assigned to specific factories for the production of trucks, ships, or construction materials, based on the plan’s directives. No enterprise could shop around for cheaper or better-quality inputs, nor could they negotiate pricing based on supply and demand. Consequently, budgets and costs were largely irrelevant—the system valued only the fulfillment of quantitative targets, such as tons of output or units produced.

This structure led to a profound absence of valuation mechanisms. Without markets, it was impossible to ascertain the true economic value or efficiency of goods and services. Value-added in production—how much worth was created at each stage—was opaque, typically measured by sheer volume rather than utility, quality, or market competitiveness.

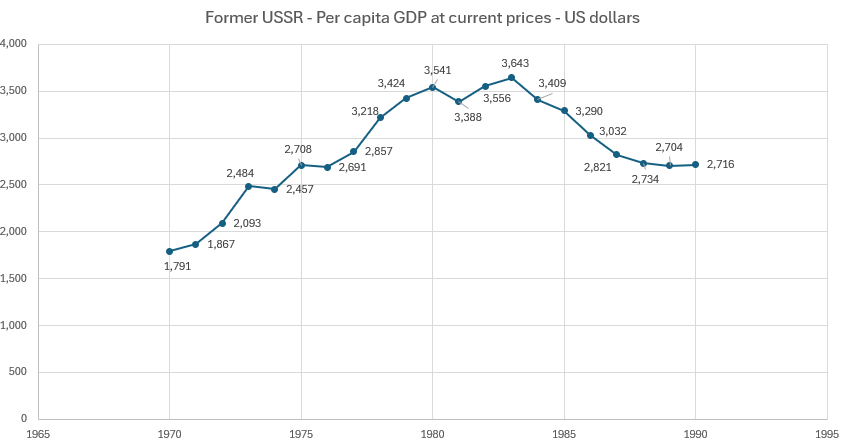

The figures from the United Nations show how the per capita GDP was falling when the Soviet Dissolution happened.

Even though the Soviet system was capable of industrial mass production, it was fundamentally flawed due to lack of market valuation mechanisms, bureaucratic determination of production flows and complete abandonment of financial profitability.

Therefore, when Soviet economists or Western observers attempted to assess the Soviet economy’s performance, the numbers could be misleading. The USSR could claim high outputs of steel, coal, or military hardware, but the economic efficiency, consumer satisfaction, and global competitiveness of these outputs remained deeply questionable.

Moreover, this system was ill-suited for cost optimization or technological upgrades, as there was no profit motive or competitive pressure to drive such changes. The Soviet leadership was thus blind to the hidden inefficiencies and wastage embedded within the economy, problems that only became apparent when the USSR collapsed and the economy was forcibly exposed to market dynamics.

Homelessness was rampant in that era as well.

Russia’s transition to a market economy has exacerbated many Soviet-era social problems. The country’s homeless population, both children and adults, has increased dramatically in the past five years. Out of a total population of 147.2 million, Russia’s homeless now number no fewer than 1.5 million, a figure that excludes the country’s several million refugees and forced migrants. Neither the Russian state nor the public has the necessary finances and will to tackle the problem. (Source: THE PROBLEM OF HOMELESSNESS IS GROWING IN RUSSIA/ Jamestown Foundation)

When the Communist illusion collapsed, what came out was lawlessness and poverty. The economy was in shambles.

The recent attempt to help Russia out of economic difficulty ranks as one of the most spectacular failures of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). In the wake of a $22 billion international loan package, Russia is in an economic morass. The only achievements of President Boris Yeltsin's administration--a stable currency and a low inflation rate--have evaporated. Foreign investors have all but written off Russia. The millions of workers and pensioners who have not been paid for months have soured on democracy and open markets. Prior to the August 17 devaluation of the ruble, Russia already was asking whether the international community was prepared to provide some additional financial support beyond the $22.5 billion promised on July 13. The G-7 countries thus far have refused to provide additional assistance, but there is increasing talk about new bailouts. (Source: "Russia's Meltdown: Anatomy of the IMF Failure" / Heritage Foundation)

Let us understand the situation based on a couple of charts.

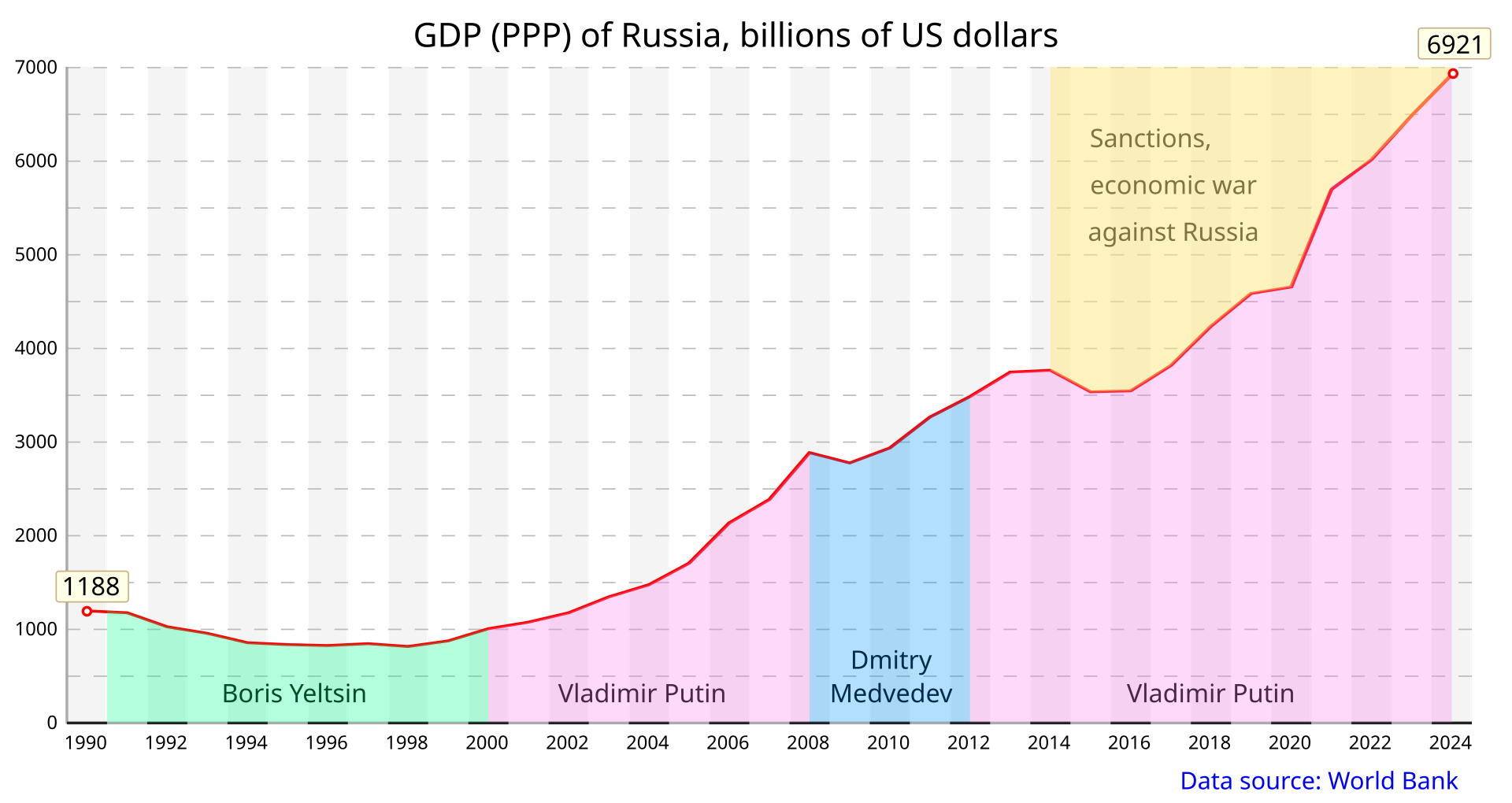

The chart below depicts Russia’s GDP (PPP) trajectory from 1990 to 2024.

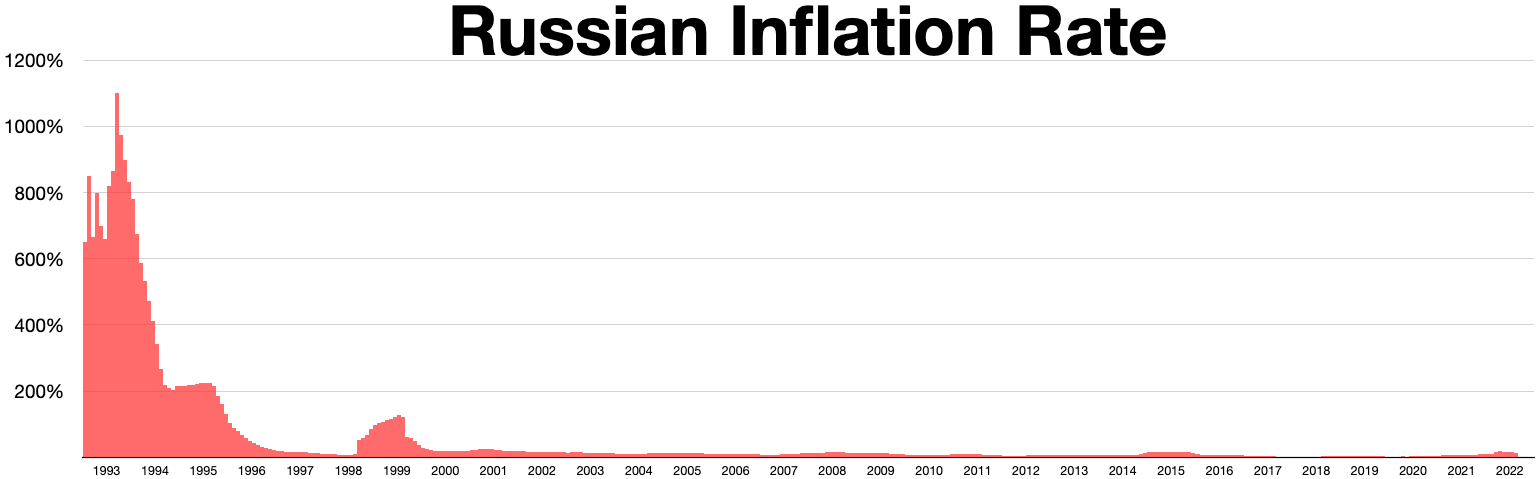

This chart depicts the inflation rate in Russia from 1993 to 2022.

As the charts reveal, Russia's GDP in PPP terms plummeted from $1,188 billion in 1990 to its lowest point throughout the 1990s.

Simultaneously, inflation skyrocketed, peaking at over 1,000% in 1992-93—a consequence of the sudden price liberalization in an economy that had previously been under price controls.

People's savings were wiped out, purchasing power collapsed, and poverty soared, with the 1998 Russian financial crisis further exacerbating the chaos, causing the ruble to collapse and resulting in defaults on domestic debt.

This period saw rampant corruption, oligarchic privatization of state assets, industrial collapse, and the degradation of social services, leading to severe declines in life expectancy, healthcare, and education standards. Society faced widespread unemployment, wage arrears, and a surge in crime and social instability.

Putin's Entry

When Vladimir Putin assumed power in 2000, the Russian economy was in disarray. His tenure marked a shift toward recentralizing power, leveraging natural resource exports (especially oil and gas), and restoring state control over strategic sectors, including Gazprom and Rosneft.

In June 2000, Vladimir Putin dismissed Viktor Chernomyrdin from his position as chairman of Gazprom's board, a critical move in reasserting state control over Russia’s energy giant. He appointed Dmitri Medvedev as Chernomyrdin’s replacement. Medvedev, who would later become Russia’s president, was a trusted ally of Putin from their time working together in the St. Petersburg mayor’s office.

Putin sought to use Gazprom to advance Russia's geostrategic interests.

The fact was that Central and Eastern Europe needed energy that they did not have. Germany needed energy for its industries. All these countries were increasingly reliant on Russia for their natural gas, particularly during the winter months.

The United States' persistent distrust of European-Russian energy interdependence is deeply rooted in its grand strategy to prevent the emergence of a dominant Eurasian bloc. The Mackinder "Heartland Theory"—which posited that control of the Eurasian landmass equates to global dominance—has long informed U.S. strategic thinking. Washington has viewed any deepening of economic or energy ties between Western Europe (especially Germany) and Russia as a direct threat to the Atlanticist order led by the U.S.

From the Cold War onwards, American policymakers, beginning with Ronald Reagan, expressed concerns that Europe’s increasing dependence on Russian natural gas—then from the Soviet Union—would translate into political leverage for Moscow over key NATO allies. Reagan vocally opposed the Urengoy-Pomary-Uzhhorod pipeline, fearing that the Kremlin could manipulate gas flows to exert influence or destabilize European resolve against the Soviet bloc.

Post-Soviet Russia’s resurgence in the 2000s, particularly under Putin’s reassertion of state control over Gazprom and strategic industries, intensified these concerns.

As early as 2000, Russia clearly tended to consolidate business

entities, as well as the shares it controlled in holding companies.

(This was the time when the consolidation of Rosneft’s subsidiaries

began in earnest. Additionally, there was the formation of the

Antey and Almaz concerns in the defense industry, the growth of the

Rosspirtprom holding company which united 89 alcohol producers, the

merger of all nuclear fuel producers and traders into one

corporation and the unification of all nuclear power plants in a

single power-generating company on the basis of Rosenergoatom,

etc.) The annual shareholders’ meetings at Gazprom, Unified Energy

Systems, Aeroflot and some other big companies in 2000 also

revealed the federal authorities’ intention of toughening their

control via corporate procedures (i.e. boards of directors). Obviously, the toughening of state control through the formation

of new big holding companies, together with the state’s broader

representation in the existing companies, was prompted by a number

of objective factors, such as the need for technological

integration and improving the companies’ ability to compete on the

market. The increased pressure on various enterprises was also

aimed at increasing budget revenues. There are certain indications

that in 2000 the government implicitly set a strategic goal

of establishing at least one state-owned ‘power center’’ in each of

the most important sectors based on the assets remaining

in state ownership (state unitary enterprises and blocks of

shares). However, such a policy faced a whole range of objective

limitations: 1) a ‘streamlined’ system of state property

management, complete with corruption and kickbacks; 2) a limited

amount of state assets that would provide for the creation of

holding companies controlled by the state; 3) in certain cases, the

need to make decisions that are viewed by investors as systemic

risks (e.g. deprivatization); and 4) political and geopolitical

factors. Still, the path of simple integration and consolidation of

state assets looked particularly attractive (compared, for example,

with such an alternative as trust management). (Source: "Russia en Route to State Capitalism?" / Russia In Global Affairs)

The power centers were being created within Russia for each important sector.

Keeping the Communist vs Capitalist critic's playbook aside, the impact of these actions by Putin was to establish these industries as "national champions" or basis of Russian stabilization and re-establishment of power structures.

Germany’s Nord Stream pipelines, bypassing Eastern Europe to deliver gas directly from Russia to Germany, symbolized to Washington a strategic realignment that threatened U.S. influence in Europe. Nord Stream 2, in particular, became a geopolitical flashpoint, with the U.S. imposing sanctions and lobbying intensely to block its completion, citing Europe's energy security risks.

This mistrust also partly explains U.S. support for energy diversification projects, such as LNG exports to Europe, the Southern Gas Corridor, and efforts to foster alternative suppliers, including Norway and Qatar. Moreover, Washington’s stance on Ukraine — a key transit state for Russian gas — has been intertwined with this strategic calculus. The U.S. sees a pro-Western Ukraine as a barrier to seamless Russian-European integration via energy and infrastructure.

In essence, American opposition to European reliance on Russian energy is not solely about "security of supply"—it reflects a broader imperial imperative to control Eurasia's connective tissues, ensuring that no rival bloc can challenge the U.S.-led global order.

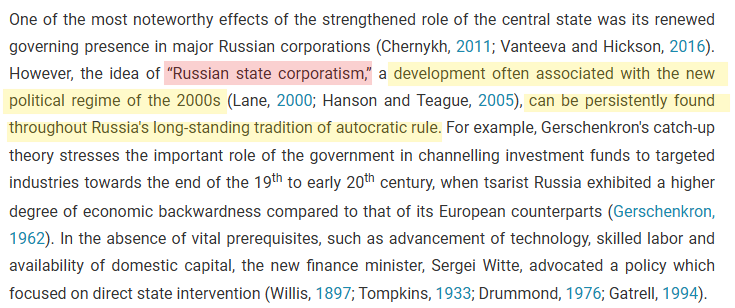

Putin's policy of "Russian State Corporatism" was criticized, even ridiculed and linked to the Russian fetish for control.

Putin's economic stabilization strategies, including tight fiscal policies, prudent macroeconomic management, and the introduction of a flat income tax, gradually reduced inflation to manageable levels by the early 2000s. Inflation, which was still volatile through the 1990s, settled below 15% by 2003, enabling financial stability.

The GDP (PPP) began a sustained rise, climbing past $3 trillion by 2008, driven by high energy prices and improved investor confidence. Additionally, Russia accumulated significant foreign exchange reserves and established a stabilization fund to buffer against commodity shocks.

Before we go on, let us discuss how the American establishment, specifically through its non-state actors like George Soros closely coordinating with the US had started undermining the Russian security as early as 1990.

How American Non-State Actors like Soros Shaped Ukraine for the War

George Soros, primarily through his Open Society Foundations (OSF), began building his involvement with Ukraine as early as 1990.

The eyes were set. The target was locked.

Now it was a matter of delivering in Ukraine.

In a document titled “Breakfast with US Ambassador Geoffrey Pyatt,” the minutes of a key meeting held on March 31, 2014, were recorded, detailing discussions between George Soros and senior U.S. and Ukrainian figures on Ukraine’s future following the Maidan coup.

During the meeting, Ambassador Pyatt explicitly emphasized the need for a coordinated PR campaign to discredit Putin and Russia’s narrative, shaping international perceptions in favor of the new Ukrainian regime. George Soros readily endorsed this proposal, aligning with Pyatt’s strategy to counter Russian influence both in Ukraine and globally.

The full details of their strategy, participants' insights, and agreed-upon initiatives are captured in the document linked below.

Was it really charity?

Hands of Soros and the American intelligence were all over the ex Soviet nations. Specifically, Ukraine and others.

In a paper titled Russian Political Warfare: Origin, Evolution and Application” by the Naval Postgraduate School, California, the funding by and involvement of Soros becomes clear as day.

It names George Soros and his organizations, including Freedom House, Development Associates, and the Renaissance Foundation. Interestingly, the authors did not find anything to be alarmed about.

Often, anything related to George Soros is dismissed as a conspiracy theory. Well, we have written in detail about Soros and his character.

As the Pyatt document clearly shows, the United States, via its non-state actors like George Soros, was working to subvert Ukraine to enter Russia and control it.

Political Evolution and the NATO Betrayal

In the mid-1990s, under Boris Yeltsin, Russia desperately sought integration into the Western-led world order, attempting to build democratic institutions and embrace free-market principles. Russia tolerated economic "shock therapy" and liberalization, expecting reciprocal goodwill, security assurances, and partnership from the West. Yet, while Russia struggled internally, NATO relentlessly expanded eastward, incorporating former Warsaw Pact countries and the Baltic states—a move directly contravening Western assurances made to Gorbachev in 1990 that NATO would not move "one inch eastward" if Germany were to unify.

This steady encroachment seeded deep distrust in Russian leadership. The First Chechen War (1994-1996) and NATO’s 1999 bombing of Yugoslavia—Russia's historical ally—without UN authorization further confirmed Moscow’s worst fears: the West sought to dominate and encircle Russia, not integrate it as an equal partner.

The rise of Vladimir Putin in 1999 marked a decisive pivot. Learning from Yeltsin's perceived Western appeasement, Putin focused on consolidating power, reasserting Russia's sovereignty, and curbing internal dissent, all while confronting NATO's growing footprint near Russia's borders. The Second Chechen War (1999-2009) and interventions in Georgia (2008) were expressions of this reassertion.

Economic Resurgence and Weaponized Sanctions

Economically, Yeltsin’s governance in the 1990s left Russia in chaos, characterized by hyperinflation, a collapsing ruble, and the rise of oligarchs through the 1995 "loans-for-shares" privatization scam. The 1998 financial crisis deepened this misery.

Under Putin, however, Russia staged a remarkable recovery from 2000 onwards, driven by high oil and gas prices and tighter control over strategic industries, such as Gazprom and Rosneft. This period restored national pride and purchasing power, yet also made Russia vulnerable to fluctuations in commodity prices.

The real economic assault came post-2014. Following the Western-backed coup in Ukraine and Russia’s reunification with Crimea, the U.S. and EU launched sweeping sanctions targeting Russia’s financial system, defense, and energy sectors. This was a clear economic war aimed at punishing Russia for resisting NATO's expansionist frontier at its doorstep.

The Betrayal and the Massacres

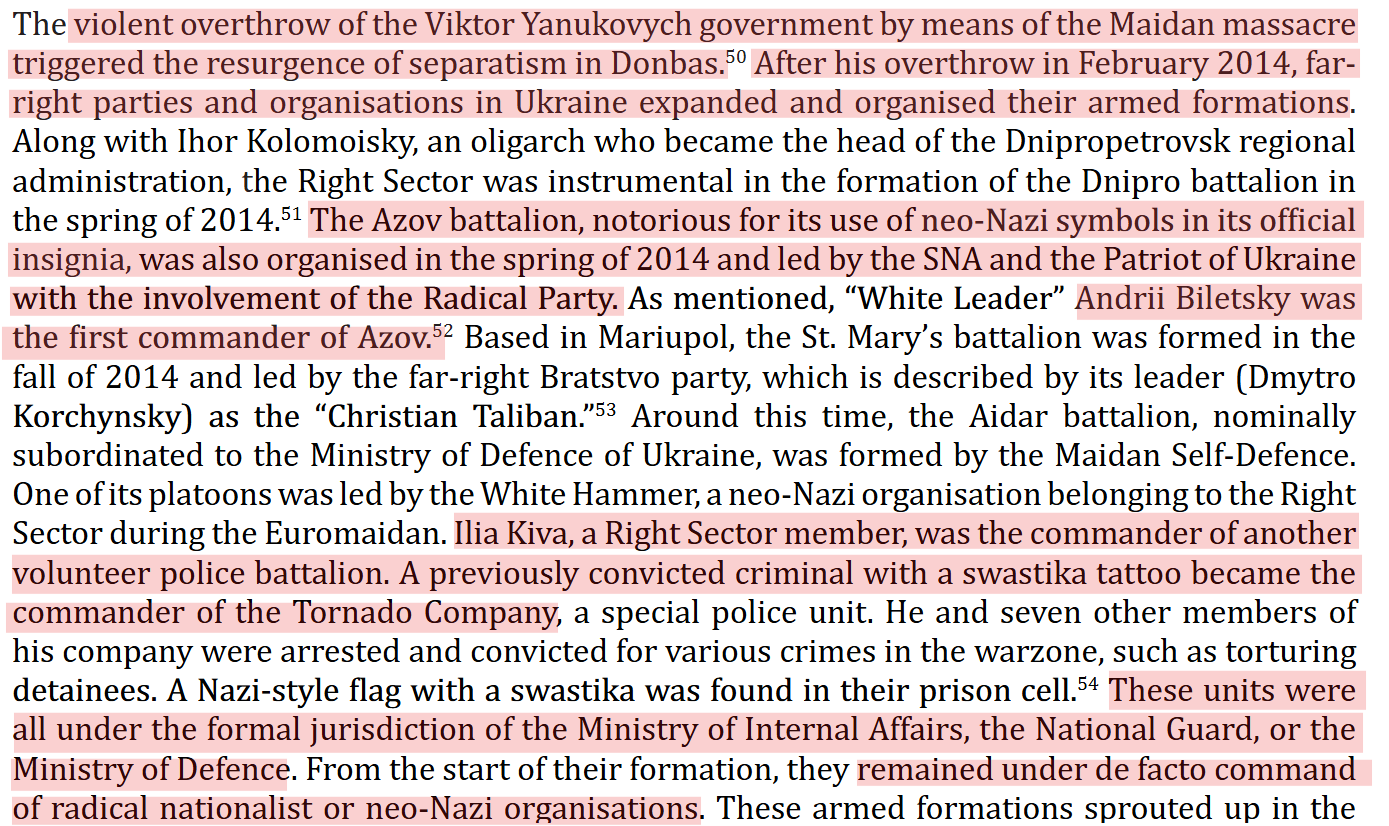

At the BRICS summit in Kazan, Vladimir Putin reaffirmed that Russia's 2022 intervention in Ukraine was not a sudden decision but the result of prolonged betrayal by the West. He recalled how he had been, in his words, “duped” by Germany and France through the Minsk Accords of 2014–15. These agreements, brokered by Germany and France under the Normandy Format, ostensibly sought to end hostilities in the Donbas by granting special autonomy to the Russian-speaking regions of Donetsk and Lugansk within Ukraine.

Yet, in December 2022, Angela Merkel publicly admitted in an interview with Die Zeit that the Minsk Accords were never meant to be fully implemented. She revealed that the agreements were a tactical maneuver to buy Ukraine time to build up its military against Russia. Former French President François Hollande corroborated this view in subsequent statements, affirming that the West’s fundamental strategy was to arm and fortify Ukraine under the guise of diplomacy.

While the European leaders were feigning to work for peace, they were actually setting up a Neo-Nazi regime in Ukraine to facilitate massacres of the ethnic Russians.

The Neo-Nazi Takeover of Ukraine Facilitated by USAID/NED/Soros

After the illegal ousting of President Viktor Yanukovych in February 2014 - orchestrated by USAID, NED, and Soros organizations- the new Kyiv regime, infused with ultranationalist and neo-Nazi elements, launched the "Anti-Terrorist Operation" (ATO) against the Donbas.

Within a year of the first Minsk accord, Ukrainian neo-Nazi battalions, such as the Azov Regiment, had taken over the armed forces of Ukraine.

You can download the file here.

However, rather than targeting militants, these operations indiscriminately attacked civilians, towns, and villages, using artillery, airstrikes, and blockades.

On May 2, 2014, the House of Trade Unions in Odessa became the site of a brutal massacre targeting those who opposed the Western-backed coup in Kyiv, often referred to by critics as a Nazi coup due to the heavy involvement of ultranationalist and neo-Nazi groups. That day, Ukrainian neo-Nazi militants, including members of the Right Sector and other extremist factions, orchestrated a deliberate and heinous attack on pro-federalization demonstrators who had sought refuge inside the building.

Contrary to the official Ukrainian narrative—which claimed the victims died from accidental fire and smoke inhalation—the reality was far more sinister. Witnesses and independent investigations have documented that many victims were murdered with firearms, bladed weapons, and were beaten to death before or during the blaze. The fire, ignited intentionally, served to cover up the mass killing and destroy evidence.

This atrocity, often referred to as the Odessa Massacre, was emblematic of the violent repression unleashed by nationalist forces in post-coup Ukraine. The massacre remains a symbol of the impunity granted to neo-Nazi militias, as to this day, Ukrainian authorities have enforced no serious investigation or accountability for the perpetrators.

By the end of 2014, over 8,000 civilians had been killed in the Donetsk and Lugansk regions—many victims of shelling in residential areas, abductions, and extrajudicial executions. The OSCE and other international observers documented these abuses, yet the Western media systematically underreported the atrocities, instead branding the victims as "pro-Russian terrorists."

The Azov Battalion, openly displaying Nazi symbols like the Wolfsangel, spearheaded these operations with ideological zeal. Reports of torture, ethnic cleansing, and the targeting of the Russian language, culture, and identity became routine. By the time of Russia’s intervention in 2022, estimates of civilian casualties in Donbas had surpassed 14,000 to 18,000 dead, with tens of thousands displaced and communities devastated.

In addition to military aggression, the Kyiv government passed legislation restricting the use of the Russian language, further marginalizing ethnic Russians and deepening cultural oppression. The combination of physical violence and cultural erasure amounted to a systematic campaign against the Donbas populace, framed by Russia as a genocidal threat against ethnic Russians.

These orchestrated massacres by neo-Nazi paramilitaries, under the tacit approval of the Ukrainian state and backed diplomatically by the West, formed the core of Russia’s justification for its 2022 military operation. While critics argue about geopolitical motives, the humanitarian crisis in Donbas—rooted in ultranationalist violence—remains a central but deliberately obscured aspect of the conflict.

The Path to the Ukraine War

Escalating tensions, broken accords, and Western-backed militarization shaped the path from the Donbas conflict to a full-scale war in Ukraine.

It began with the 2014 Western-supported Maidan coup in Kyiv, which ousted the pro-Russian President Viktor Yanukovych. This power shift brought to prominence ultranationalist and neo-Nazi elements, notably the Azov Battalion and Right Sector, who spearheaded violent crackdowns on dissent, particularly in the Russian-speaking east.

In response, Donetsk and Lugansk regions declared independence, leading to the Donbas war, where Ukrainian forces and neo-Nazi militias waged a brutal campaign against the separatists and civilians, resulting in over 14,000 deaths by 2021 (UN data).

To halt the conflict, the Minsk Accords (2014-2015) were signed, promising autonomy for Donbas. However, Western leaders like Angela Merkel later admitted these agreements were never intended for peace but to buy time for Ukraine to build military strength (Die Zeit, 2022).

Despite Russia’s calls to implement Minsk, Ukraine—backed by the US, NATO, and EU—continued military buildups and NATO integration talks. The US supplied weapons, training, and intelligence to Ukrainian forces, further militarizing the frontlines. Meanwhile, neo-Nazi militias were integrated into Ukraine's National Guard, with minimal Western condemnation.

By early 2022, Ukraine intensified shelling in Donbas, prompting Russia to recognize the Donetsk and Lugansk People’s Republics. Fearing NATO's encroachment and citing the ongoing Donbas genocide, Russia launched its “Special Military Operation” in February 2022, aiming to “demilitarize and denazify” Ukraine.

Western nations, led by the US and EU, flooded Ukraine with arms, funding, and intelligence, escalating the conflict into a proxy war against Russia. The refusal to negotiate on security guarantees, combined with NATO’s eastward expansion, ensured that what began in Donbas evolved into a full-fledged, geopolitically charged war engulfing Ukraine.

This is how the US and European countries laid the bait for Russia to enter into a war against Ukraine, which was at best a proxy for those countries.

Let us understand how Russia transformed from its humble beginnnings in post-Soviet collapse in 1990 to today.

The Russian Military Transformation

After the Soviet collapse, the Russian military was in disarray. Russia inherited an enormous but unsustainable military-industrial complex.

The Russian armed forces faced chronic underfunding, resulting in obsolete equipment, poor logistics, and widespread corruption. Morale among troops was severely depleted due to low pay, inadequate training, and crumbling infrastructure. This combination rendered the military ineffective and unprepared for modern warfare throughout the 1990s, exposing deep vulnerabilities in Russia’s post-Soviet defense capabilities.

The First Chechen War (1994-1996) exposed the Russian military’s operational incompetence. Russia’s forces were ill-equipped for modern, asymmetric warfare, suffering heavy losses and global embarrassment.

The key issues at that time were:

- Budget cuts from $246 billion (USSR 1991) to less than $15 billion by the mid-90s.

- Conscription crisis: poorly trained and low-morale conscripts.

- High-ranking corruption in defense procurement.

- Military-industrial sector collapse with brain drain and factory closures.

The Russo-Georgian War of 2008 served as a critical wake-up call for Moscow. While Russia achieved a swift military victory, the conflict laid bare significant weaknesses within its armed forces.

The war exposed the army's slow mobilization, highlighting its inability to deploy rapidly. It also revealed poor coordination between the different military branches, leading to operational inefficiencies.

Furthermore, Russia's communications and C4ISR systems—responsible for command, control, intelligence, and surveillance—were severely outdated, impairing real-time battlefield awareness.

These shortcomings prompted Russian leadership to initiate comprehensive military reforms aimed at modernization, professionalization, and restructuring to prevent such vulnerabilities in future conflicts.

In response, Defense Minister Anatoly Serdyukov and Chief of General Staff Valery Gerasimov initiated radical military reforms, known as the "New Look" reforms. These included:

Structural Reorganization: Transition from a division-based structure to brigade-based formations for faster deployment and flexibility. Reduced officer corps by half to professionalize leadership.

Professionalization: Downsizing of the bloated Soviet-style conscript army. Greater emphasis on creating a professional soldier cadre under contract service (kontraktniki).

Joint Command Systems: Establishment of unified command structures to improve joint operations between Army, Navy, and Air force.

Streamlined Logistics: Simplification of military districts into larger, more efficient commands.

Modernization Drive - 2011

In 2011, Russia launched the ambitious State Armament Program (SAP-2020), worth approximately 20 trillion rubles (around $700 billion), with a focus on modernizing weaponry, infrastructure, and technological capabilities.

Russia’s military modernization, particularly since 2011, has profoundly transformed its strategic, precision, and technological capabilities, reshaping the country’s ability to project power both regionally and globally.

At the core of Russia’s deterrence is its Strategic Nuclear Forces, which have undergone significant upgrades. The deployment of the RS-24 Yars, a modern intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) with multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs), has bolstered Russia’s nuclear triad.

Complementing this is the introduction of the Avangard hypersonic glide vehicle, capable of traveling at speeds exceeding Mach 20, rendering existing missile defense systems ineffective. Russia is also fielding the Sarmat ICBM, designed to replace the Soviet-era SS-18 Satan, with the capacity to deliver a variety of warheads across continents.

In the realm of precision weaponry, Russia developed the Kalibr cruise missile, which demonstrated its long-range, high-precision strike capability during the Syrian conflict. These missiles, launched from ships and submarines, can hit targets thousands of kilometers away with remarkable accuracy, signaling Russia’s leap in conventional strike options.

The Russian Air Force has also seen significant revitalization. The development of the Su-57, Russia’s first stealth multirole fighter, alongside the highly maneuverable Su-35, enhances air superiority capabilities.

Along with that the S-400 and S-500 air defense systems now offer advanced anti-aircraft and missile defense capabilities, reportedly effective against fifth-generation fighters and ballistic missiles.

In naval terms, Russia has shifted focus to smaller, more agile ships outfitted with precision strike capabilities, moving away from legacy large vessels. The Northern Fleet has been revamped to reinforce Russia’s strategic posture in the Arctic, a region of growing geopolitical importance.

Finally, Russia has advanced in Electronic Warfare (EW) and cyber capabilities, deploying systems like Krasukha-4 to disrupt enemy communications and radar. Integrated cyber operations further bolster Russia’s capacity for hybrid warfare, blending kinetic and non-kinetic strategies.

Doctrinal shifts

Russia’s 2014 Military Doctrine marked a strategic shift in response to rising NATO threats and Western encroachment. The doctrine emphasized asymmetric warfare, leveraging tactics designed to counter technologically superior adversaries, and reinforced the importance of nuclear deterrence as the cornerstone of national security.

A key conceptual evolution was the so-called Gerasimov Doctrine, which blended non-military means, such as cyber operations, disinformation campaigns, and political subversion, with traditional military force to achieve strategic objectives without direct large-scale war.

Russia’s 2015 intervention in Syria became a practical demonstration of this evolved strategy. It displayed Russia’s enhanced expeditionary capabilities, with swift deployment and sustained operations far from home.

The campaign effectively integrated air, land, and naval forces, including precision airstrikes supported by naval-launched cruise missiles. Syria also served as a critical testing ground for modernized weapons systems, allowing Russia to refine tactics, assess combat effectiveness, and showcase its revived military power globally.

The Economic Miracle

In 1991, the Soviet Union—the largest geopolitical entity of the 20th century—collapsed. What emerged was not merely a new state, but a broken, impoverished, and deeply unstable polity. By 1995, Russia stood on the precipice of collapse.

The economy had contracted by nearly 40% since 1991, wages became worthless overnight due to hyperinflation peaking at 2,500%, and pensions went unpaid. The ruble was a joke on global markets, and the infamous “shock therapy” economic reforms—pushed by Western economists—led to mass privatization, handing control of vital industries to a handful of oligarchs. Meanwhile, lawlessness gripped the regions: mafia groups dictated terms to local governments, Chechnya declared independence, and the state’s monopoly on violence was all but nonexistent.

The Russian state was crippled—militarily, economically, and institutionally. Public services barely functioned, the average life expectancy for men fell to 57 years, and an estimated one in three Russians lived below the poverty line. The perception within Russia was that the West had not only defeated the Soviet Union but humiliated and looted Russia in its aftermath.

Into this vacuum of chaos stepped Vladimir Putin in 1999—a former KGB officer, relatively unknown but deeply embedded in the mechanics of state power.

When Putin took over in 1999 as Acting President, the Russian Federation’s GDP was a mere $195 billion. The nation was under a crushing debt-to-GDP ratio of over 90%, inflation stood at 36.5%, and foreign reserves were dangerously low at $12.6 billion.

Putin’s first decade in power focused on stabilization and consolidation:

- Fiscal Reforms and the Oil Dividend

- Russia introduced a flat income tax of 13%, encouraging compliance and improving state revenues.

- The government consolidated the sprawling and corrupt tax system, boosting collections and plugging leakages.

- The state reasserted control over energy assets, most notably via the dismantling of oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky’s Yukos Oil and strengthening state behemoths like Gazprom and Rosneft.

- Inflation Control and Sovereign Funds

- Inflation was methodically brought down from 36% in 1999 to just 3.5% by 2023, restoring confidence in the ruble.

- Russia repaid its IMF and Paris Club debts early, achieving fiscal sovereignty.

- The Stabilization Fund of Russia was established in 2004, channeling oil windfalls into reserves that by 2023 totaled $600.8 billion—the world’s fourth-largest reserve hoard.

- Debt Reduction

- Russia's debt-to-GDP fell from 90% to just 23% by 2023, thanks to disciplined budgeting and surplus-driven management.

- Putin also leveraged debt repayments as geopolitical strategy—paying down obligations to remove IMF and Western influence from internal policy-making.

- GDP and Income Growth

- The economy expanded from $195 billion in 1999 to over $2.2 trillion in 2023, despite fluctuations caused by sanctions and global crises.

- Per capita income rose from $1,330 to over $14,000, moving Russia into the ranks of upper-middle-income nations.

Vladimir Putin’s policies reshaped Russian society in ways that seemed unthinkable during the chaotic 1990s. One of the most significant achievements was the substantial reduction in poverty.

From a staggering 30% of the population living below the poverty line in the 1990s, the rate was cut by half within a decade of Putin’s leadership, reflecting the impact of macroeconomic stability and state-driven social programs.

Wages saw a meteoric rise. The average monthly salary skyrocketed from just 1,523 rubles (about $53) in 1999 to over 65,000 rubles (~$850) by 2023, vastly improving the purchasing power of Russian households.

Pensions, once symbolic of state neglect, transformed spectacularly, from a mere 449 rubles (~$15) in 1999 to 19,320 rubles (~$250) by 2023, uplifting millions of elderly citizens.

Equally critical was the dramatic fall in unemployment. From post-Soviet highs of 13% in the late 1990s, joblessness dropped to around 5%, reaching even lower levels during the recent war mobilization period. This stability in employment reflected both the reinvigoration of the industrial base and the expansion of the public sector. Together, these changes fueled a social revival that reestablished dignity and stability for the Russian populace.

Reviewing Putin's "Authoritarianism'

Putin’s Russia is often condemned in the West for its so-called authoritarianism, but such criticisms ignore the hostile geopolitical context in which these actions emerged.

He curtailed the autonomy of regional governors, established federal districts with presidential envoys, and reasserted Moscow’s authority to prevent the country's fragmentation.

Without such recentralization, Russia risked becoming a balkanized wasteland of competing fiefdoms—just as Western strategists desired.

Judicial and tax reforms were essential pillars of this consolidation. The legal system was overhauled, not just to attract investment but to establish order where mafia and oligarchs once reigned. Simplified tax structures boosted compliance and revenues, giving the state financial independence.

Far from being mere authoritarianism, these measures were the bedrock of Russian sovereignty, ensuring that Russia could act decisively—economically, politically, and militarily—in a world where the West sought its permanent subjugation.

Comments ()