The Coming Silver and Copper Catastrophe

Silver and Copper shortages are not structural but they are systemic in nature. The demand and supply scenarios and the current actions by US and options with the adversaries point to only one eventuality - a catastrophe.

The Bell, the River, and the Empty Mountain

A long time ago, in a valley fed by a restless river, there stood a monastery famous for its bell.

The bell was not gold.

It was forged of red metal and white metal, blended just right, and when struck, its sound traveled farther than the eye could see.

Kings relied on it to mark time. Merchants relied on it to open markets. Soldiers relied on it to begin and end wars.

For generations, the monks rang it once each dawn. No more. No less.

One year, the bell’s voice weakened.

The sound no longer crossed the valley. The echoes died early. The people complained.

A young monk asked the abbot, “Master, why has the bell grown silent?”

The abbot replied, “The bell has not changed. The mountain has been emptied.”

Downriver, beyond the monastery’s sight, the red metal was being torn from the earth faster than the river could carry away the scars. The white metal was no longer gathered patiently—it was seized, hoarded, rushed, and hidden.

Men with maps arrived. Then men with contracts. Then men with weapons.

They said, “We need the metal to build a cleaner future.” But they burned forests to reach it.

They said, “We bring order.” But the river ran black.

One night, a great flood came. Not of water, but of absence.

The mines collapsed. The roads broke. The river changed its course.

The men who took everything discovered they had taken too much, too fast, and now the mountain had nothing left to give—neither metal nor mercy.

The villagers begged the monks to ring the bell harder.

The abbot refused.

“You cannot strike harder what has already been hollowed,” he said. “When extraction replaces reverence, sound becomes noise. When speed replaces balance, power becomes collapse.”

Years later, grass returned to the riverbanks. Small hands learned again how to pan patiently. The bell was recast—not larger, but lighter.

It did not ring as far.

But it rang true.

Teaching:

Those who believe strength comes from control will always strike first. Those who understand balance wait—and outlast.

The mountain does not wage war. It simply stops answering.

And when the metals fall silent, so does the empire that depended on them.

SUPPORT DRISHTIKONE

In an increasingly complex and shifting world, thoughtful analysis is rare and essential. At Drishtikone, we dedicate hundreds of dollars and hours each month to producing deep, independent insights on geopolitics, culture, and global trends. Our work is rigorous, fearless, and free from advertising and external influence, sustained solely by the support of readers like you. For over two decades, Drishtikone has remained a one-person labor of commitment: no staff, no corporate funding — just a deep belief in the importance of perspective, truth, and analysis. If our work helps you better understand the forces shaping our world, we invite you to support it with your contribution by subscribing to the paid version or a one-time gift. Your support directly fuels independent thinking. To contribute, choose the USD equivalent amount you are comfortable with in your own currency. You can head to the Contribute page and use Stripe or PayPal to make a contribution.

The Capture in Caracas

On January 3, 2026, the U.S. carried out an operation in Venezuela to capture Venezuelan President Maduro.

Washington justified this as combating “narco-terrorism” and forcing regime change. Following the capture, Vice President Delcy Rodríguez was installed as interim president. The U.S. asserted control over Venezuelan oil exports and moved to lift some sanctions to rebuild the industry under U.S. influence. This intervention has drawn international controversy and heightened geopolitical tensions with China, Russia, and regional actors.

It is being reported that the US may have used a sonic weapon to cause people there to vomit blood as well.

The immediate impact would be the US taking over Venezuela and its resources.

The US will "run" Venezuela until a "safe, proper and judicious transition" can be ensured, Donald Trump has said, after US strikes led to the capture of country's President Nicolas Maduro. US oil companies would also fix Venezuela's "broken infrastructure" and "start making money for the country", the US president said. (Source: "Donald Trump says US will 'run' Venezuela and 'fix oil infrastructure'" / BBC)

And it will not be a very short engagement either. Now he is saying that this will go in for many years.

President Trump said on Wednesday evening that he expected the United States would be running Venezuela and extracting oil from its huge reserves for years, and insisted that the interim government of the country — all former loyalists to the now-imprisoned Nicolás Maduro — is “giving us everything that we feel is necessary.” “Only time will tell,” he said, when asked how long the administration will demand direct oversight of the South American nation, with the hovering threat of American military action from an armada just off shore. (Source: "Trump Says U.S. Oversight of Venezuela Could Last for Years" / New York Times)

After the operation, US has seized 5 tankers going out of Venezuela in the last one week. These included two Russian-flagged tankers.

The operation comes two days after US forces seized two oil tankers, including the Russian-flagged Marinera oil tanker, originally known as the Bella-1. The US Department of Justice has since said it was investigating the crew of the ship, which was seized in the northern Atlantic, for failing to comply with coastguard orders and would pursue charges. (Source: "US seizes fifth oil tanker as Venezuela pressure campaign continues" / Al Jazeera)

The U.S. interdiction of five oil tankers linked to Venezuela marks a significant escalation in Washington’s effort to control Venezuelan oil flows and enforce sanctions.

These seizures are not isolated law-enforcement actions but part of a broader maritime blockade under Operation Southern Spear aimed at crippling sanction-evasion networks and preventing crude exports outside U.S.-approved channels.

Geopolitical implications are profound.

Russia and China condemnation: Moscow has condemned the seizures as “piracy” and a potential breach of international law, heightening U.S.–Russia tensions and risking naval or diplomatic friction. China, a major buyer of Venezuelan oil, has likewise criticised U.S. unilateralism, which may push Caracas closer to Beijing and Moscow.

Legal and maritime norms tested: Targeting a Russian-flagged tanker on the high seas raises complex questions about flag state consent, use of force in international waters, and the legality of sanctions enforcement beyond territorial seas.

Regional instability and market shifts: Latin American governments may view the blockade as an infringement on sovereignty, stoking anti-U.S. sentiment. Oil market dynamics could shift as Venezuelan crude is redirected or withheld, impacting global prices.

Overall, these seizures deepen the Venezuela crisis, entangle great-power rivalry, and set precedents for sanctions enforcement at sea.

This phase of U.S. operations against Venezuela signals a far broader geopolitical recalibration, extending well beyond oil and regime pressure. At stake is the future architecture of critical mineral supply chains, which underpin military power, semiconductors, AI, and energy systems.

By reasserting control over Venezuela’s resource space, Washington is not merely weakening Caracas—it is pre-empting China’s long-term strategy to lock in upstream access to minerals across the Global South.

Beijing’s model depends on distressed states, opaque contracts, and weak governance. The U.S. intervention disrupts that playbook, turning Venezuela from a Chinese hinterland into a contested node in the emerging resource war that will define 21st-century power.

While oil exports have long defined Venezuela's economic profile, the U.S. administration is reportedly eyeing the nation's wealth of critical minerals. These include gold, nickel, bauxite (used in aluminum production), and coltan (used for producing electronic devices). Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick stated over the weekend that Venezuela possesses "steel, minerals, all the critical minerals, they have great mining history that’s gone rusty." However, extracting these resources presents formidable challenges. Christopher Ecclestone, mining strategist at Hallgarten & Company, points out that Venezuela's confirmed minerals, excepting gold, are relatively cheap compared to copper, lithium, or tin mined elsewhere in South America. (Source: US Seeks Venezuela's Critical Minerals: AI Race Fuels Geopolitical Shift / Whalesbook)

Also read: U.S. May Seek Critical Minerals In Venezuela To Diversify Supply Chain / Forbes

South America and US interests

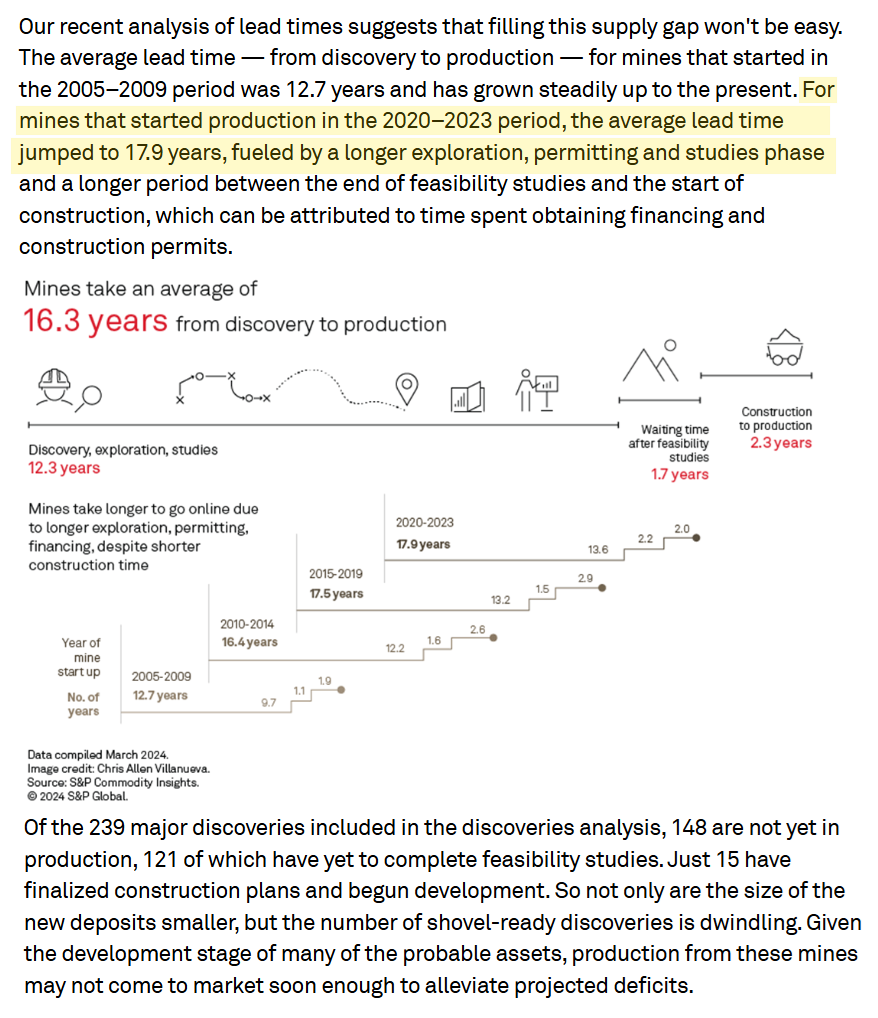

The U.S. foreign policy framework — as articulated in its national security strategy — emphasizes reducing dependence on China for critical resources and keeping Latin America within Washington’s strategic orbit.

Will Chile and Peru be next?

One doesn't think so - and we will go into other tools like subversion that US has already used.

Economic and Trade Levers and covert operations are the greatest levers that US has against them.

Silver and Copper: The Coming Catastrophe

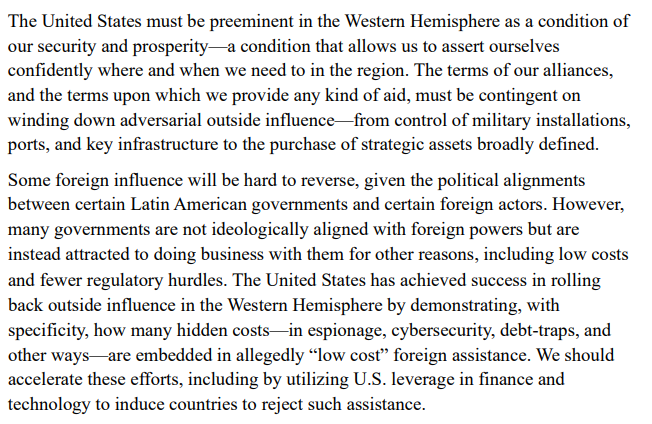

Global copper and silver markets face unprecedented structural deficits driven by converging technological, industrial, and geopolitical forces. Silver has recorded five consecutive years of supply shortfall, while copper demand is projected to surge 50% by 2040, creating a supply gap of 10 million metric tons.

These shortages aren't caused by temporary disruptions but by fundamental mismatches between demand trajectories and supply architectures.

In these times, it is imperative to understand the dynamics of these two metals and the geopolitical situations around them.

Copper's role in electrification, artificial intelligence infrastructure, and defense systems makes it a "systemic risk" to economic growth.

Silver's dual identity as both an industrial input and a monetary asset creates unique stress patterns in which physical demand immobilizes supply while investment flows amplify price volatility.

Let us first understand the structural forces driving these shortages. We will look at the geopolitical forces and dimensions that are rarely discussed because some of the concerned geographies aren't deemed important enough!

The Copper Time Horizon Problem

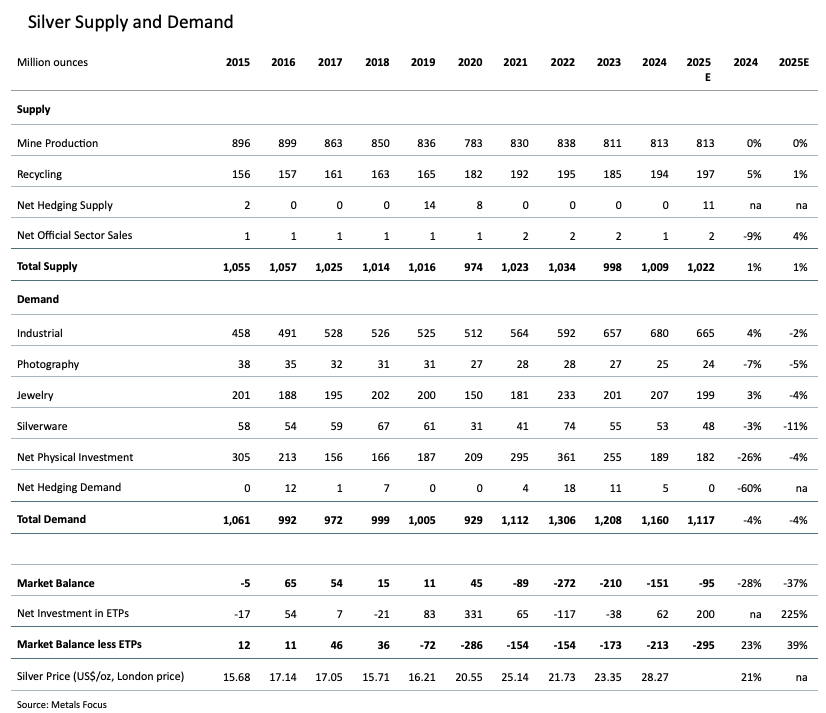

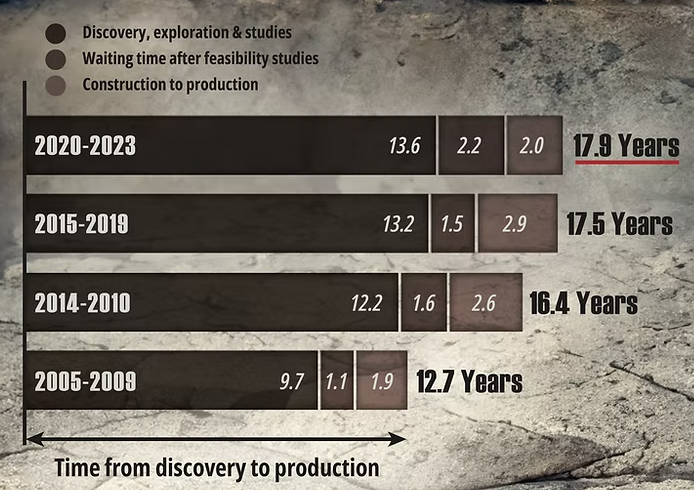

Copper production faces a brutal arithmetic: demand growth outpaces supply expansion by design, not accident. Bringing a greenfield copper mine from discovery to first production these days requires, on average, ~ 18 years.

You can also see it in this visual for more clarity.

Researchers warn that between 2018 and 2050, the world will need to extract 115% more copper than has been mined in all of human history up to 2018 merely to sustain business-as-usual growth.

This staggering requirement does not even account for the full weight of the green energy transition.

Once global electrification, especially the shift to electric vehicles, is factored in, the numbers become geopolitically significant.

Remember this statistic:

This is not an industrial challenge alone; it is a strategic one.

Large copper deposits are geographically concentrated, politically contested, and increasingly subject to resource nationalism, environmental opposition, and great-power competition.

Recently, a very large mine closed due to a catastrophe.

The shutdown was not a routine interruption but an open-ended suspension, instantly removing a critical pillar of global copper supply.

Given Grasberg’s scale, the impact rippled across international markets, tightening an already constrained system and exposing the fragility of global mineral dependencies.

Restart plans stretch cautiously into 2026–2027, underscoring that once a mega-mine fails, capacity cannot be quickly or easily replaced.

The Grasberg episode stands as a stark warning: the global copper supply chain is one accident away from systemic disruption.

Roughly 40% of output from these new mines would be absorbed just by EV-related grid upgrades, tightening supply further.

Failure to meet this mining cadence risks turning copper into a chokepoint commodity—one that can reshape alliances, empower producer states, intensify U.S.–China competition, and determine who controls the infrastructure of the electrified future.

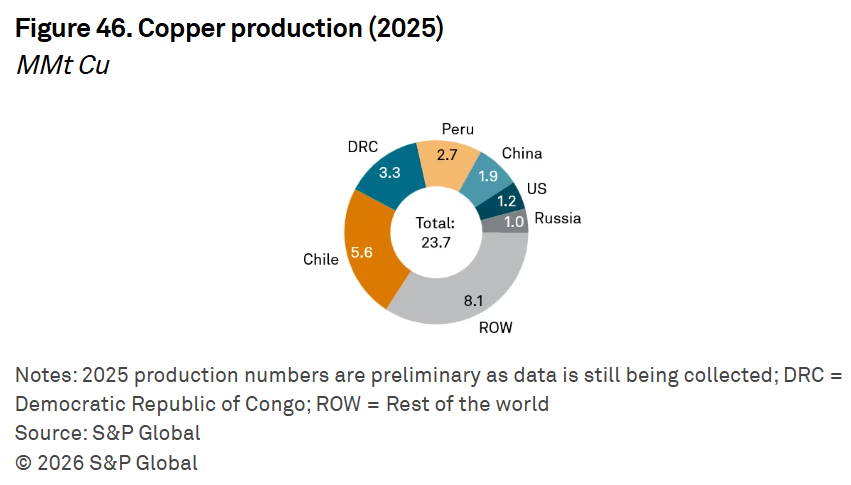

Major copper reserves are concentrated in Chile, Peru, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and China.

Each jurisdiction presents distinct constraints.

Chile and Peru together supply roughly 40% of the world’s mined copper, but both are grappling with mounting political volatility.

Mining companies, scarred by overinvestment during the early 2000s commodity supercycle, remain capital-conservative. BCG analysis shows insufficient new capacity coming online to meet 2030 demand.

BCG (Boston Consulting Group) analyses highlight significant potential shortfalls in new capacity, particularly for data centers and critical materials like copper, to meet soaring 2030 demand driven by AI, with insufficient infrastructure investment and slow project development creating supply gaps.

Reports show projected increases in data center energy consumption (up to 100-130 GW in the U.S. by 2030), while key resources like copper face demand exceeding supply by 20-30%.

These capacity constraints, coupled with challenges in energy supply and grid readiness, pose a significant risk of failing to meet burgeoning tech and energy needs without massive, coordinated investment and policy action.

For years, tech giants have been at the vanguard of corporate action on climate, with some pledging to reach net zero by the end of this decade. But the rush to develop AI is throwing that timeline into doubt. After decades of stagnant growth, US energy demand is surging, thanks in large part to the power-hungry chips and data centers that AI hyperscalers—the tech companies at the forefront of AI development—need to train large language models (LLMs) and embed AI into consumer-facing applications as well as the steady migration of business operations to the cloud. Moreover, AI’s thirst for energy is set to intensify. Electricity demand for US data centers is projected to rise by 15% to 20% annually, reaching 100 to 130 gigawatt hours in 2030, according to BCG analysis. That’s enough to power two-thirds of US households. (Source: Power Moves: How CEOs Can Achieve Both AI and Climate Goals / Boston Consulting Group)

The industry faces a coordination failure: individual firms rationally avoid billion-dollar bets on 20-year projects when copper price cycles can destroy returns within 5 years. Yet collective underinvestment creates future scarcity.

S&P Global's 2026 study identifies AI infrastructure and defense spending as demand accelerants beyond the electrification baseline.

Data centers powering large language models require massive electrical distribution systems—copper-intensive by definition. Defense modernization programs, particularly in precision-guided munitions, electronic warfare, and autonomous systems, add to copper demand that doesn't respond to price signals. Governments will pay.

Silver's Byproduct Curse

Silver's supply structure differs fundamentally. Only 30% of global silver production comes from primary silver mines; 70% arrives as a byproduct of copper, lead, zinc, and gold mining.

This means the silver supply cannot quickly respond to price increases. When silver prices surge, zinc mine operators don't accelerate production—they optimize for zinc economics.

The byproduct structure creates an inelastic supply.

The output from the mines has remained essentially flat despite silver prices rising 67% in 2025 to record highs. The Silver Institute reports 2025 mine supply increased only 1%, while demand dynamics shifted dramatically.

This has been a dramatic year for the silver market, with record metal prices, an unprecedented liquidity squeeze resulting in record-high lease rates, record volumes being delivered into CME vaults as a reflection of tariff concerns in the US, and silver being officially designated as a critical mineral by the US government. These developments coincide with elevated macroeconomic and geopolitical risks, including US trade policy, prompting investors to lift allocations to precious metals for portfolio diversification. As a result, investment demand has strengthened noticeably, comfortably offsetting the weakness across all key areas of silver demand. Against this backdrop, the silver price hit a record high and posted a 67% year-to-date gain to November 6. This eclipses the 52% rise for gold and the 14% increase for the S&P 500. In terms of market fundamentals, global supply is estimated to rise by 1%, underpinned by a modest return to producer hedging. Global demand is expected to decline by 4%, with all significant demand categories posting lower totals. Even so, the market has remained in deficit in 2025, marking the fifth consecutive year. (Source: The Silver Market is on Course for Fifth Successive Structural Market Deficit / The Silver Institute)

Recycling provides marginal relief. Secondary supply responds to price—Indian households sold 100 tonnes of old silver in one week during price spikes. But recycling volumes cannot close structural deficits measured in thousands of tonnes annually.

Silver's Industrial Transformation

Here is the critical piece that one must remember:

Solar photovoltaic panels use silver in conductive pastes that are essential to cell efficiency.

Each panel requires 10-20 grams; marginal efficiency gains cannot eliminate silver entirely without performance trade-offs.

This article argues that Silver has jumped about 67% year-to-date and recently hit a record of around 54 dollars per ounce, surpassing the famous 1980 and 2011 spikes.

Unlike many past rallies that were dominated by speculative investors, this run is rooted in industrial demand, especially from the solar photovoltaic (PV) sector.

Solar panel manufacturing now consumes a very large and fast‑growing share of global silver output, as PV capacity additions surge worldwide. Even though manufacturers are trying to “thrift” silver use per panel and experiment with substitutes, the sheer scale of solar installations means total silver demand from PV remains structurally high.

Supply constraints are being felt everywhere. Mine supply and recycling are not keeping pace with this new industrial pull, contributing to tight physical markets, high lease rates, and persistent deficits.

Solar manufacturers are responding by looking for ways to reduce silver intensity, redesign cell technologies, or shift to alternative materials, but these transitions are slow and uncertain at commercial scale.

Because a large slice of silver demand is now tied to long‑term decarbonization and solar build‑outs, the article suggests that the old price ceiling near 30 dollars is unlikely to return soon without a major global slowdown.

AI and Data Centers: Need for Copper

S&P Global's 2026 research identifies artificial intelligence as a demand vector that wasn't modeled in previous copper forecasts. Training large language models requires data centers with power densities far exceeding traditional facilities.

A single AI-optimized data center can consume 50-100 megawatts—equivalent to powering 50,000 homes.

This power must be distributed through copper bus bars, cables, and cooling systems. Backup power systems, redundancy architecture, and grid interconnections multiply copper intensity. The AI buildout occurs in parallel to electrification, compounding total demand.

Defense spending follows similar logic. Modern warfare centers on electronic systems, precision guidance, and networked command and control.

Aircraft, warships, submarines, and coast guard vessels rely heavily on copper for wiring, propulsion systems, communications, radar, and power distribution. Its exceptional resistance to corrosion, especially in saltwater and extreme environments, ensures reliability, durability, and long service life under combat conditions where failure is not an option.

Beyond platforms, copper’s strategic value deepens through its alloys. When combined with metals such as nickel, zinc, and lead, copper forms high-strength alloys used in military hardware, munitions, and protective systems. These materials are engineered to absorb shock, resist fatigue, and withstand sustained mechanical and thermal stress. From armored vehicle components to body armor elements and weapons systems, copper alloys provide the balance of toughness, flexibility, and resilience that modern defense technologies demand.

As warfare becomes increasingly electrified, networked, and sensor-driven, copper’s role only expands.

Copper: The Electrification Imperative

Copper demand from renewable energy and electric vehicles follows exponential, not linear, trajectories.

The International Energy Agency's Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2025 positions copper as essential to decarbonization pathways.

Recent green policy commitments, such as the EU Green Deal, the US Inflation Reduction Act, and China's dual carbon goals, are locking in copper demand regardless of commodity cycles.

India's emergence as Asia's leading source of oil demand growth paradoxically increases copper needs.

Transportation electrification may lag the West, but India's grid expansion, manufacturing buildup, and urbanization are driving massive investment in electrical infrastructure.

Copper demand correlates with electricity consumption growth, and India's per capita usage remains far below OECD levels.

All these things together have brought their own complexities to these two resource-rich and civilizationally old countries.

Chile and Peru.

Let us take a stock.

Subverting Chile

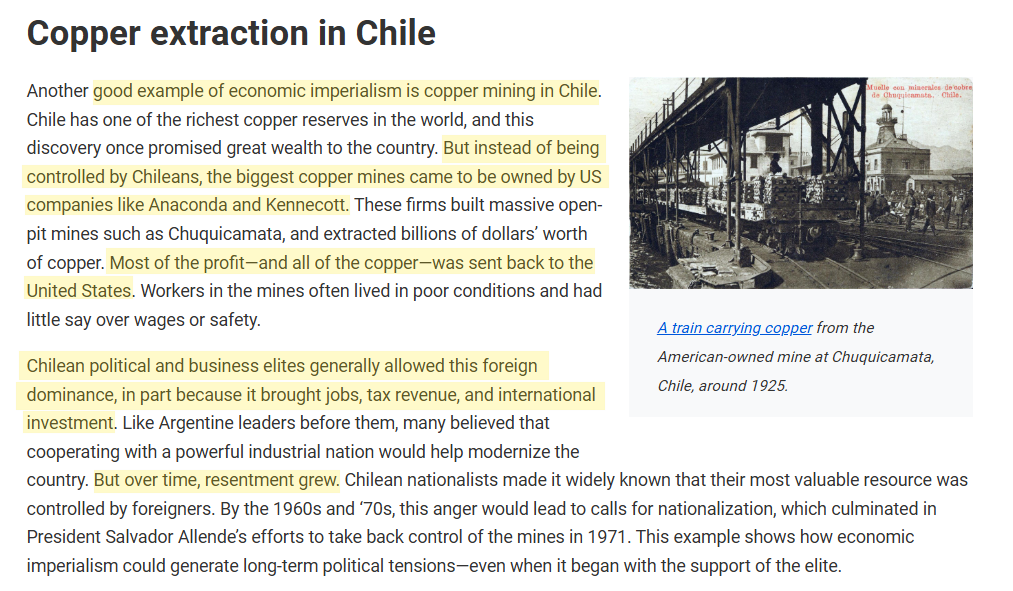

Resource-rich Latin American countries have faced subversion from Western powers through economic imperialism, political interference (like coups/support for dictators), and corporate exploitation, often leveraging natural resource wealth (oil, minerals, agriculture) for foreign profit while undermining local sovereignty, creating dependency, and fueling inequality through methods like debt, conditional aid, and backing elites who favor foreign investment over national development, as seen in historical US interventions and ongoing resource extraction conflicts.

Chile's copper reserves - it's greatest wealth - also became its greatest curse. For, the United States would ensure that Chile could never be independent in its own governance.

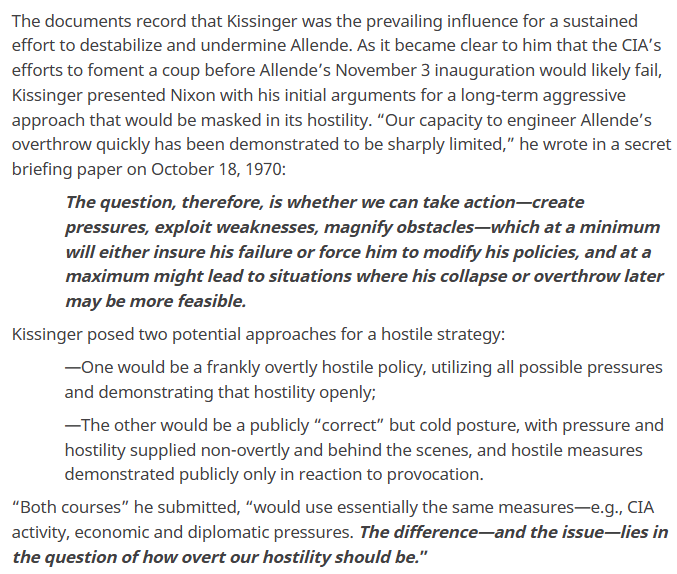

Several days after Salvador Allende’s history-changing November 3, 1970, inauguration, Richard Nixon convened his National Security Council for a formal meeting on what policy the U.S. should adopt toward Chile’s new Popular Unity government. Only a few officials who gathered in the White House Cabinet Room knew that, under Nixon’s orders, the CIA had covertly tried, and failed, to foment a preemptive military coup to prevent Allende from ever being inaugurated. The SECRET/SENSITIVE NSC memorandum of conversation revealed a consensus that Allende’s democratic election and his socialist agenda for substantive change in Chile threatened U.S. interests, but divergent views on what the U.S. could, and should do about it. “We can bring his downfall, perhaps, without being counterproductive,” suggested Secretary of State William Rogers, who opposed overt hostility and aggression toward Chile. “We have to do everything we can to hurt [Allende] and bring him down,” agreed the secretary of defense, Melvin Laird. “Our main concern in Chile is the prospect that [Allende] can consolidate himself and the picture projected to the world will be his success,” President Nixon explained as he instructed his national security team to adopt a hostile, if low-profile, program of aggression to destabilize Allende’s ability to govern. “We’ll be very cool and very correct, but doing those things which will be a real message to Allende and others.” (Source: Allende and Chile: ‘Bring Him Down’ / US National Security Archives)

The hatred for Salvador Allende, a leader who wanted to stand Chile on its own terms, was evident in White House circles. The question was never whether to subvert Chile! But how overt should it be?

Remember, hostility or not was never the question.

“Both courses” he submitted, “would use essentially the same measures—e.g., CIA activity, economic and diplomatic pressures. The difference—and the issue—lies in the question of how overt our hostility should be.”

Intensifying constitutional debates in Chile, protests over environmental damage, and indigenous rights campaigns are injecting significant uncertainty into the permitting landscape. In Peru, revolving-door governments and recurring anti‑mining demonstrations are already slowing project timelines and approvals.

Chile is now ruled by the right. Currently, the Executive (President) is José Antonio Kast, a right-wing, conservative, law-and-order nationalist. Something like Donald Trump. He will take office in March 2026. The outgoing President is Gabriel Boric. He is a left, progressive person.

Chile did not move right because voters embraced conservative philosophy.

It moved right because:

- Security became the dominant issue (crime, gangs, migration)

- The left lost moral authority (Caso Convenios scandals)

- Constitutional fatigue discredited transformational politics

- The political center collapsed, leaving voters to choose extremes

The 2019 estallido social shattered the legitimacy of Chile’s post-Pinochet political settlement. While the demand for change was real, the institutional response faltered. Two successive constitutional replacement efforts: one dominated by the radical left (2022) and another by the right (2023) - were both rejected by voters.

This produced deep constitutional fatigue and a loss of faith not only in elites, but in the very process of reform itself. The government of Gabriel Boric, elected as a symbol of generational and moral renewal, quickly ran into structural limits.

The economic slowdown, weak congressional coalitions, and, especially, the Caso Convenios corruption scandal stripped the progressive camp of its ethical advantage. At the same time, Chile experienced a sharp rise in violent crime, gang activity, and migration-linked insecurity—less severe than in much of Latin America, but unprecedented in Chilean memory. Public psychology shifted faster than institutions could respond.

Overlaying this is the long-running Mapuche conflict in southern Chile. What began as a historic land and identity struggle has partially mutated into a hybrid zone where legitimate indigenous grievances coexist with criminalized violence, arson, and illicit economies. State responses—oscillating between dialogue and militarization—have satisfied no one and reinforced perceptions of state weakness.

These dynamics collapsed the political center and polarized the electorate. The 2025 election of José Antonio Kast reflects not a coherent ideological revolution but a demand for order, borders, and authority amid exhaustion with perpetual transition.

Internationally, most major powers do not benefit from Chilean instability. The United States, the European Union, and China all have strong interests in Chile’s copper and lithium, which are critical to the energy transition and industrial supply chains. Chaos raises costs and delays projects. The true beneficiaries of instability are transnational criminal networks and domestic political entrepreneurs who thrive in fear-driven politics.

In short, Chile’s “chaos” is the product of legitimacy erosion, security shocks, territorial conflict, and reform overreach—an advanced democracy struggling to reset without consensus.

Peru has had pretty much the same history.

Subverting Peru

In Peru, too, the story seems very similar.

The CIA subverted the country's polity as well.

During the Fujimori era, Washington strongly supported Alberto Fujimori’s presidency, even as he carried out an autogolpe (self‑coup) in 1992 and ruled in an increasingly authoritarian fashion.

Fujimori’s intelligence chief Vladimiro Montesinos had deep links to the CIA, and U.S. backing continued through harsh counterinsurgency and neoliberal restructuring.

Some deals, including one that failed, were done through third countries. Like the one where Jordan was to sell 50,000 surplus AK-47s to the Peruvian military. However, they ended up in the hands of leftist guerrillas in Colombia.

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, cooperation on counterinsurgency and counternarcotics entrenched ties between Peruvian security forces and U.S. agencies, giving Washington considerable influence over Peru’s security agenda.

In recent times, left-leaning President Pedro Castillo was removed from office after he attempted to illegally dissolve Congress and proclaim an “emergency government,” a move widely described by Peruvian institutions and most international observers as a failed self-coup. Congress responded by impeaching him on grounds of “moral incapacity,” and Vice President Dina Boluarte assumed the presidency.

From prison, Castillo accused the United States of helping engineer his ouster and of encouraging the military to repress protests in order to clear the way for mining interests. These claims, however, remain allegations and have not been substantiated by mainstream judicial or institutional investigations. Washington swiftly condemned Castillo’s attempt to dissolve Congress, welcomed Boluarte’s accession, and initially supported her government—even as security forces killed dozens of protesters, largely poor and Indigenous Peruvians, in crackdowns that drew serious human-rights criticism.

Critical left and anti-imperialist commentators argue that a “U.S.-backed” order was consolidated in the aftermath. They point to the U.S. ambassador’s meetings with Peru’s defense leadership shortly before Castillo’s removal, continued diplomatic backing for Boluarte, authorization for more than a thousand U.S. troops to enter Peru in 2023, and policy shifts to liberalize lithium and other mining sectors that Castillo had sought to place under stronger state control.

The attempted assassination of a popular cumbia band in Lima on October 8 proved to be the spark that ignited Peru’s long-simmering political crisis. What initially appeared to be a criminal incident quickly escalated into a national reckoning, exposing the depth of public anger over insecurity, corruption, and chronic political instability. Within forty-eight hours, the crisis had overtaken the state itself.

On October 10, President Dina Boluarte was removed from office, marking yet another abrupt end to an already fragile administration. Congress swiftly moved to install José Jerí as Peru’s new head of state, making him the country’s eighth president in just ten years—a stark statistic that underscores how normalized political turnover has become. Rather than restoring calm, the transition inflamed public outrage.

In the days that followed, tens of thousands of Peruvians poured into the streets in what have become the largest protests the country has witnessed in the past five years. Demonstrators denounced not only the latest change in leadership but the broader political system itself, which many view as incapable of delivering security, accountability, or economic stability. Protesters’ demands ranged from early elections and constitutional reform to an end to elite impunity.

The state’s response further intensified tensions. Violent clashes between protesters and security forces erupted in multiple cities, leaving at least one person dead and dozens injured. Images of tear gas, burning barricades, and armed police confronting civilians reinforced a growing perception that Peru is trapped in a cycle of crisis management rather than genuine governance.

What began as an isolated act of violence thus revealed a deeper truth: Peru’s instability is no longer episodic. It is structural, rooted in eroded trust, weak institutions, and a political order that repeatedly fails to absorb social shock without breaking.

Peru's situation has not changed over many decades. It is a manifestation of state fragility inside a formally democratic shell: presidents come and go, but the underlying drivers remain the same:

- Congressional opportunism,

- public distrust,

- corruption, and a

- security breakdown tied to organized crime.

All these keep the system in permanent crisis mode.

Peru is one of the world’s leading producers of copper, silver, zinc, and other strategic minerals, making mining the backbone of its economy. Multinational firms from the United States, Canada, Europe, and increasingly China dominate extraction and exports. High-profile disputes—most notably around the Las Bambas copper mine—have repeatedly exposed how state coercion and security force deployments are used to protect mining operations against sustained rural and Indigenous resistance.

Now, Peru has become a sharper node in US–China competition because Chancay can reshape Pacific trade routes and strategic access. Organized crime is now a national security variable, not just a public safety issue. Weak institutions increase the risk of “criminal governance” in parts of the economy. And most importantly, there is a regional stability risk. Peru’s volatility affects Andean security cooperation and the dynamics of cross-border trafficking.

Over the past three decades, Peru has entrenched a policy framework shaped by free-trade agreements, strong investor protections, and macroeconomic orthodoxies aligned with the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. This structure has locked the country into a broadly neoliberal model, sharply constraining space for resource nationalism or redistributive reform. While Peruvian elites increasingly welcome Chinese capital, the overall system continues to anchor the economy to Western financial norms and corporate interests.

Chaos, Instability, and Copper

If domestic instability deepens in either country, whether through large‑scale strikes, asset nationalization drives, or prolonged protest waves, the impact on global copper flows could be severe.

Against this backdrop, resource nationalism is likely to gain traction as a political instrument.

Governments with more interventionist or left‑leaning agendas in Latin America may turn to higher windfall taxes, tighter export controls, or demands for majority state stakes in key assets. Faced with this policy uncertainty, mining firms will scale back or defer capital spending, reinforcing a cycle of chronic underinvestment and future supply tightness.

Geopolitical Ramifications

De-Dollarization and Commodity-Backed Trade

BRICS+ expansion and US sanctions weaponization drive de-dollarization efforts. Russia-China CIPS-SPFS payment system interlinking enables non-dollar commodity trade.

Copper and silver could serve as trade collateral in bilateral arrangements, removing supply from dollar-denominated markets.

Commodity-backed trade finance instruments—where physical metal secures credit lines—could proliferate. China's Belt and Road infrastructure financing increasingly uses resource-for-infrastructure swaps. Copper and silver become geopolitical chips, not just industrial inputs.

Central bank reserve diversification includes record gold purchases.

Silver's monetary history suggests it could reenter reserve calculations if shortages persist and prices rise. Central banks accumulating silver removes supply from industrial use, tightening markets further.

Taiwan and Semiconductor Coupling

Taiwan produces 60%+ of advanced semiconductors.

They are the chips that power everything from mobile phones to electric cars—and they make up 15% of Taiwan’s GDP. Taiwan produces over 60% of the world’s semiconductors and over 90% of the most advanced ones. Most are manufactured by a single company, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corporation (TSMC). Until now, the most advanced have been made only in Taiwan. (Source: Taiwan’s dominance of the chip industry makes it more important / The Economist)

These chips use copper interconnects and require silver during manufacturing.

A Taiwan contingency—conflict, blockade, or unification pressure—would disrupt semiconductor supply and the metal inputs feeding those fabrication plants.

Semiconductor sovereignty efforts in the US, EU, Japan, and India aim to reduce Taiwan's dependence. But building fabs requires copper and silver. The race to secure semiconductor capacity drives up demand for critical minerals, creating self-reinforcing shortage cycles.

Metal Scarcity as Systemic Force

Copper and silver shortages go beyond commodity market imbalances.

They reflect deeper structural tensions between technological ambition and geological reality, between globalization and sovereignty, between economic efficiency and strategic security.

The convergence of electrification, artificial intelligence, defense modernization, and investment demand creates metal requirements that existing supply architectures cannot satisfy. These aren't demand spikes—they're demand regimes. The world is fundamentally shifting toward higher metal intensity per unit of economic activity.

Supply response lags by a decade or more. This lag embeds scarcity into the 2030s regardless of policy action taken today. Prices will rise until demand destruction occurs or substitution becomes economically viable. But governments pursuing climate targets and technological supremacy will resist demand destruction, perpetuating shortages.

Geopolitically, metal scarcity creates new fault lines. Resource-rich states gain leverage. Resource-poor states face industrial constraints unless they secure supply through alliances, stockpiles, or military capability. Critical minerals became strategic assets comparable to oil in the 20th century.

The transition won't be smooth. Price volatility, export restrictions, mine nationalizations, and supply chain fragmentation will characterize the next 15 years. Companies must build resilience through geographic diversification, strategic inventory, and substitution R&D. Governments must balance industrial policy, climate goals, and geopolitical competition.

The metal crunch is not a crisis to be solved—it's a condition to be managed. Success requires recognizing that copper and silver are no longer commodities trading on supply-demand fundamentals alone. They are strategic materials embedded in the context of great power competition, technological races, and the energy transition.

Nations that secure supply chains for these metals will lead the next industrial era. Those that fail will face constraints on growth, security, and technological sovereignty.

The shortage begins now. The consequences unfold over decades.

Drunken Knight Opening - Destruction of the Geopolitical Escalatory Ladder

Whichever path the looming silver and copper shortages take, one conclusion is unavoidable: the contest over metal commodities is sliding into a geopolitical Wild West, where restraint gives way to raw power and survival instincts rule.

The United States is already acting with a kind of “Drunken Knight Opening”—aggressive, disruptive, and deliberately destabilizing the board. It creates chaos rather than balance. But the mistake is to assume the other players are passive. They are not. They are observing, recalculating, and preparing—quietly, patiently, and without illusion.

When one actor demonstrates a willingness for total demolition rather than calibrated pressure, adversaries stop planning proportional responses. They plan for annihilation. The logic shifts decisively: not how to deter, but how to survive—and if necessary, how to end the game entirely.

What follows is not a ladder of escalation but a collapse of it. These geo-economic maneuvers resemble first-strike doctrines: sudden, overwhelming, and designed to eliminate the opponent’s ability to respond.

In such a world, metals are no longer commodities. They are strategic weapons—and the struggle over them is no longer about leverage, but about extinction-level dominance.

The response of US adversaries will assume the geopolitical second strike nuke scenario of geopolitics.

Comments ()