The Price of Sovereignty: From Tashkent to Tianjin

From Shastri’s mysterious death in Tashkent to Modi’s guarded moves in Tianjin, India’s pursuit of true sovereignty has come at a deadly cost. This issue traces the unseen hand of empires, the battles for autonomy, and the price every nation pays for daring to stand alone.

The Lantern and the Shadow

Once, in a mountain monastery, a young monk found an ancient lantern.

Its light was warm, steady, and pure. He carried it through valleys and storms, and wherever he went, darkness seemed to retreat.

One night, a group of travelers came from across the seas. They admired the lantern and said,

“Your light is beautiful. But it shines too freely. Let us guard it for you — so it may not fall into wrong hands.”

They took the lantern, placed it in a box of mirrors, and told him,

“See, now it shines brighter than before!”

But the monk looked closely. The mirrors only reflected the light inward, never out. The lantern began to suffocate from its own glow.

When they slept, he quietly opened the box. The air rushed in; the flame flickered weakly, then steadied again — small but alive.

Years passed. Many tried to buy or break the lantern. Some offered gold, others threats. But the monk learned a lesson written in the wind:

And so, he carried his fragile lantern into the storm once more —

not to conquer the darkness, but to remind it that the mountain still remembered dawn.

Context:

- The monk is India — patient, ancient, luminous.

- The lantern is its civilizational sovereignty and independent will.

- The foreign travelers represent the Western powers that try to “manage” India’s rise.

- The box of mirrors is the illusion of protection and partnership that drains vitality.

- The act of opening the box reflects the Shastri–Modi continuum — moments when India breaks free of imposed order, even at great risk.

SUPPORT DRISHTIKONE

In an increasingly complex and shifting world, thoughtful analysis is rare and essential. At Drishtikone, we dedicate hundreds of dollars and hours each month to producing deep, independent insights on geopolitics, culture, and global trends. Our work is rigorous, fearless, and free from advertising and external influence, sustained solely by the support of readers like you. For over two decades, Drishtikone has remained a one-person labor of commitment: no staff, no corporate funding — just a deep belief in the importance of perspective, truth, and analysis. If our work helps you better understand the forces shaping our world, we invite you to support it with your contribution by subscribing to the paid version or a one-time gift. Your support directly fuels independent thinking. To contribute, choose the USD equivalent amount you are comfortable with in your own currency. You can head to the Contribute page and use Stripe or PayPal to make a contribution.

The 1965 Ceasefire

An IDSA article argues that India’s 1965 ceasefire decision was not a blunder or the result of General Chaudhuri misleading Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri, but a complex choice shaped by military stalemate, diplomatic isolation, and the looming China threat.

By mid-September, the war had reached a deadlock around Lahore and Sialkot. India had achieved its main aim—repelling Pakistan’s offensive—but further gains seemed unlikely without heavy losses. Although claims persist that India had ample ammunition and tanks left, the official records show only a modest advantage and genuine logistical concerns. On September 20–21, after consultations with Defence Minister Chavan and General Chaudhuri, Shastri approved the UN-brokered ceasefire. The advice was influenced by fears of Chinese intervention—Beijing had issued threats and mobilized forces—and by mounting international pressure from the U.S., U.K., and USSR, all demanding an end to hostilities.

By declaring a ceasefire with effect from 3.30 a.m. on 23 September 1965, did India miss an opportunity to attain decisive victory over Pakistan? Yes, according to the existing narrative, which attributes the ceasefire decision solely to the advice tendered in this regard by General J. N. Chaudhuri, the then Chief of the Army Staff and Chairman of the Chiefs of Staff Committee. In this account, Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri was willing to consider extending the war “for some days” if the Indian Army could attain “a spectacular victory” in that timeframe.1 But Chaudhuri advised Shastri to agree to an immediate ceasefire because he was under the ‘false’ impression that the war effort could no longer be sustained given that “most of India’s frontline ammunition had been used up and there had been considerable tank losses also.”2 The reality was, however, quite different. By 22 September, the Indian Army had used up only 14 per cent of its frontline ammunition and it possessed “twice the number” of tanks than the Pakistan Army.3 In contrast, the Pakistan Army is believed to have been “short of supplies” and “running out of ammunition” by then.4 And a high attrition rate was “daily reducing the number of operational aircraft available” to the Pakistan Air Force.5 As argued by K. Subrahmanyam, under these circumstances, if India had continued the war “for another week, Pakistan would have been forced to surrender.”6 (source: The Context of the Cease-Fire Decision in the 1965 India-Pakistan War / IDSA)

Part of the deal for the ceasefire included returning of Haji Pir and Tithwa heights. A deal that was devastating for many in the Indian Army and something for which PM Shastri's wife was extremely upset with him on.

On January 10th, 1966, the landmark (famous and infamous as different camps of analysts would like to call it) Tashkent Agreement was signed between India's Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri and Pakistan's President Ayub Khan, under the mediation of Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin.

The signing ceremony was at 4.00 PM. After having signed the most significant agreement of his time, Shastri returned to his villa. It was a Soviet-provided dacha about 250 yards away from where the rest of the Indian delegation was staying.

In 10 hours everything changed.

Before turning in that night, Shastri telephoned his family in Delhi.

According to his wife Lalita Shastri and his sons Anil and Hari, his tone was unusually bright.

He told them:

“I have some good news to share when I return.”

He added cryptically that the news would:

“Send the opposition into turmoil and eclipse all protests about the Tashkent Declaration.”

Family members and researchers later linked this remark to Shastri’s interest in solving the mystery of Subhas Chandra Bose’s disappearance.

After all, in late 1965, Shastri had promised Amiya Nath Bose, Netaji’s nephew, that he would use his Tashkent trip to pursue clues about Bose in Soviet archives.

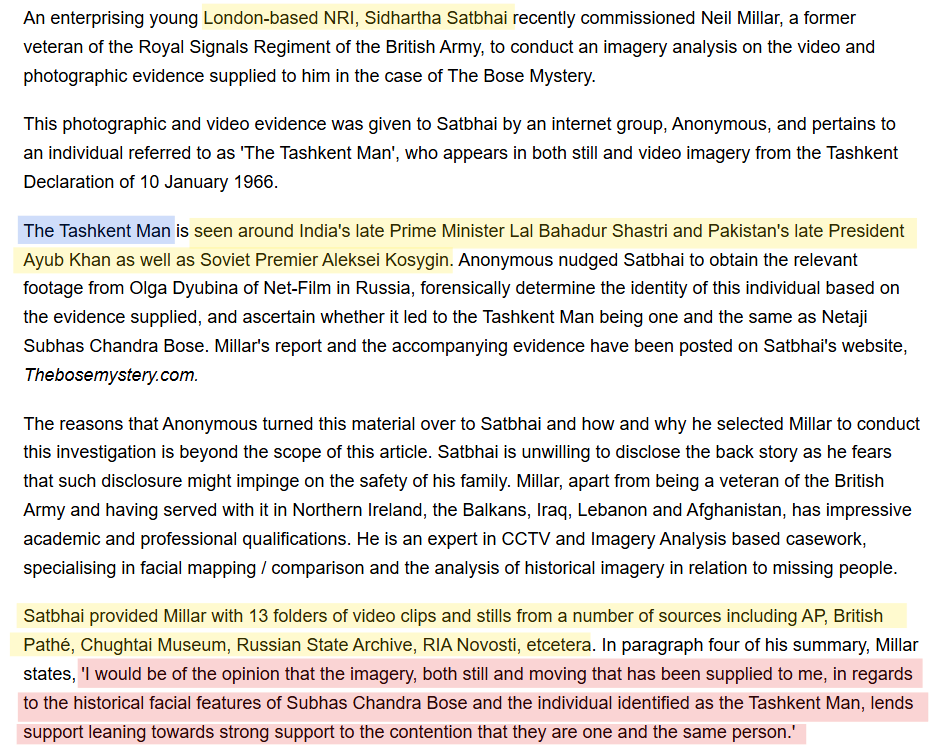

In Tashkent, the pictures taken during signing of the Tashkent Agreement showed an interesting person.

The Tashkent Man.

Who was he? According to some, he was Netaji himself.

Pictures of the Tashkent Agreement capturing the "Tashkent Man"

Well, the resemblance was so uncanny that one London-based NRI Sidhartha Satbhai planned to have it professionally investigated.

So what was Netaji doing in the Tashkent Agreement photo op?

Also see - "Netaji files: Tashkent angle may divulge new facts about Bose's death" / India Today

There does seem to be an uncanny similarity of the mysterious "Tashkent Man" with Netaji. Here is a closer glimpse.

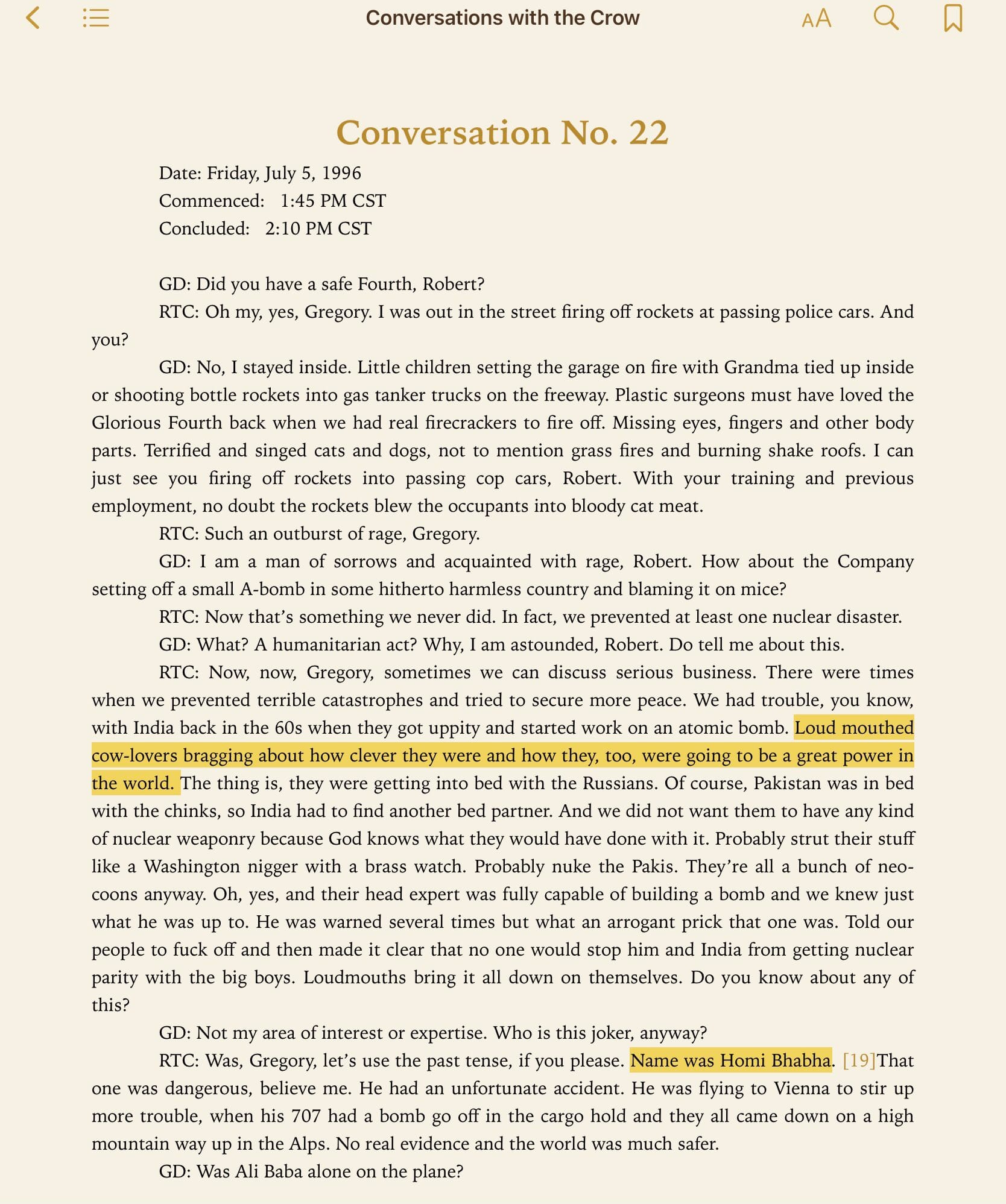

The events during that night are worth remembering.

After the signing of the historic Tashkent Declaration, Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri attended a reception hosted by Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin. Eyewitnesses recall him as calm, cheerful, and visibly relieved after the tense days of negotiation. Around 10 p.m., Shastri returned to his dacha, accompanied by his personal physician Dr. R.N. Chugh and his assistant Ram Nath.

According to the official medical log and eyewitness accounts, he ate a light dinner prepared and served by Ram Nath around 10:30 p.m. Later, he made a telephone call to his family in Delhi — a brief but emotional conversation during which he mentioned having “some good news” to share upon his return. His family later believed this “good news” referred to something significant he had learned in Tashkent, possibly related to Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose.

Shortly after the call, Shastri allowed Prem Prakash of ANI and N.S. Thapa of the Films Division to photograph him through his window. The dimly lit images, showing Shastri pacing and occasionally looking outside, became iconic — the haunting “silhouette shots” that captured his final hours. These were the last moving images of India’s second Prime Minister, taken just before midnight on January 10, 1966 — hours before his mysterious death that would ignite decades of speculation, suspicion, and unanswered questions about what really happened that night in Tashkent.

The trouble started at midnight.

According to the official reconstruction and the testimony of Ram Nath and Dr. Chugh:

- 12:30 AM: Shastri, preparing for bed, asked Ram Nath to go eat and rest.

1:20 AM: The Prime Minister appeared at the door of his staff’s room, clutching his chest and gasping.

“Call the doctor,” he whispered.

Dr. Chugh was awakened immediately and began examination.

Within minutes, Shastri’s breathing became labored, and he lost consciousness.

The doctor called for local Soviet doctors, and by 1:25 AM, Dr. E.G. Yeremenko, a senior Soviet physician, arrived with a team.

Despite administering an intramuscular injection, artificial respiration, and cardiac massage, revival failed.

At 1:33 AM, Lal Bahadur Shastri was declared dead.

Here are some important questions:

- Despite his previous two heart attacks, there was no oxygen tank in his room.

- Intramuscular injections were used instead of intravenous, delaying drug effectiveness.

- As one Soviet doctor reportedly told journalist K.R. Malkani: “Revival would have been possible only if death was due to heart failure.”

So was the cause of death something other than the cardiac arrest? That is what the Soviet doctor was implying.

When Shastri’s body returned to Delhi, family members were horrified. His face had turned blue, and white patches were visible on his temple.

Cardiologists later told his sons that such marks could indicate a toxic substance or snake venom-type poison causing brain hemorrhage.

Interestingly, what transpired post assassination of PM Shastri defies logic. Hours after Shastri’s death, the 9th Directorate of the KGB arrested:

- Soviet butler Ahmed Sattarov

- Fellow cooks

- Jan Mohammad, personal cook of Indian Ambassador T.N. Kaul

They were detained on suspicion of poisoning Shastri — yet no investigation followed in India, and the cooks were quietly released.

The obvious questions are:

- If the KGB suspected poisoning, why did the Indian delegation conclude “heart attack”?

- Why no post-mortem even after arrests?

As if this was not enough, things took a bizarre turn once the last rites had also been done.

The two key eyewitnesses later met grim fates:

- Dr. R.N. Chugh died in a car crash along with his wife.

- Ram Nath, Shastri’s aide, was crippled in another car accident and later died as well.

Both deaths occurred before any formal inquiry could take their testimonies.

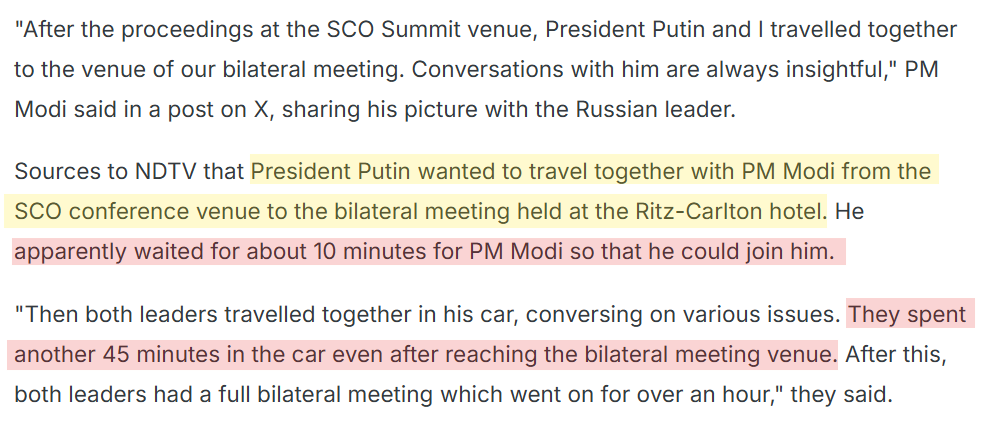

Within 13 days of Shastri’s death, Dr. Homi J. Bhabha, India’s top nuclear scientist and the man personally empowered by Shastri to develop India’s nuclear program, died in a plane crash near Mont Blanc, France.

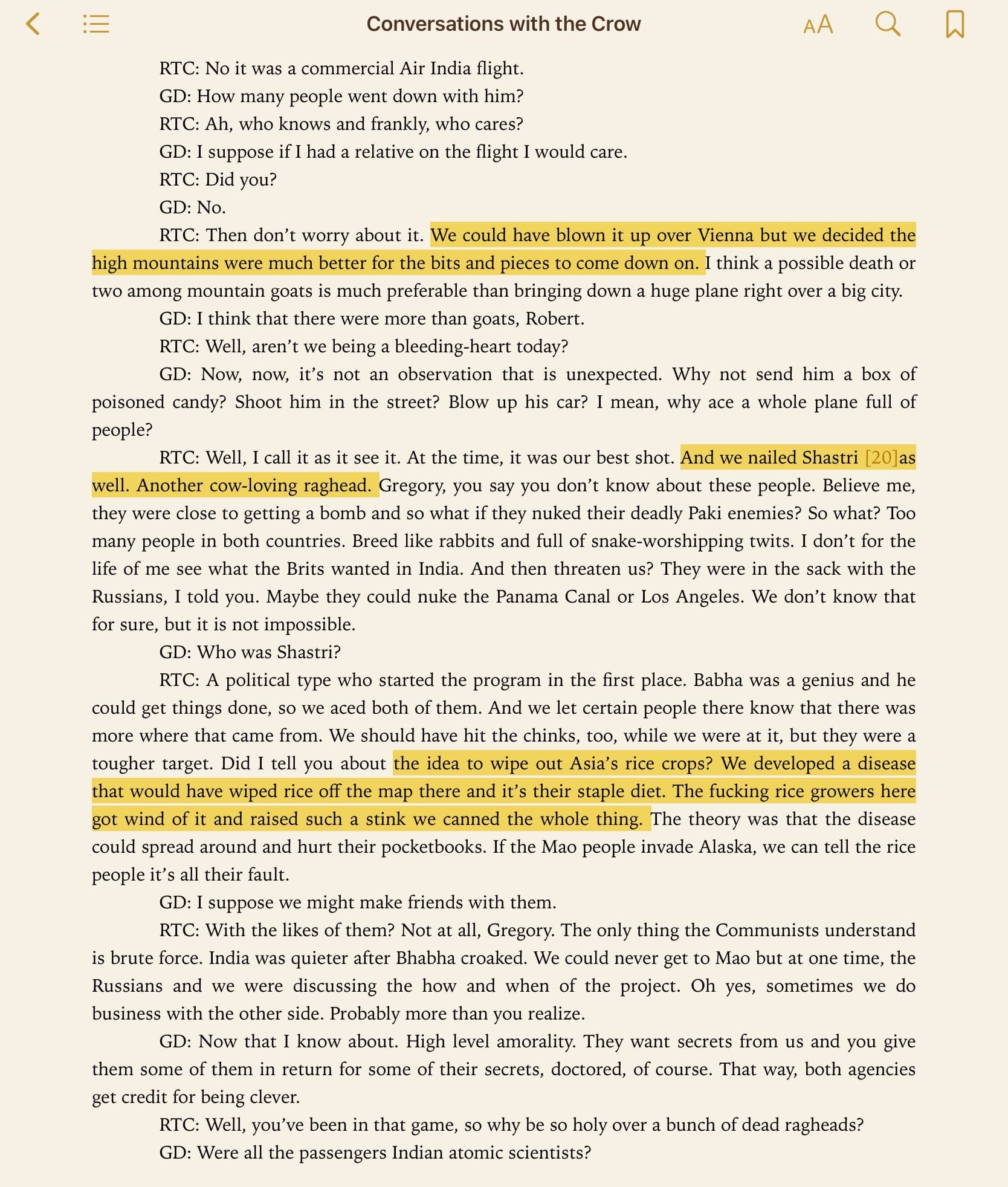

These were confessions of Robert Crowley, the second in command of the CIA's Directorate of Operations (in charge of covert operations), as recorded in a book by Gregory Douglas titled Conversations with the Crow. The book was based on based on Crowley’s interviews with Gregory Douglas.

“The ragged-looking, cow-loving Indian leader had come close to building a bomb with Bhabha’s help. It became crucial for us to get him out of the way… We nailed Shastri and knocked up Bhabha.”

This claim aligned with Western fears that Shastri’s nuclear ambitions and non-alignment policy were veering India out of U.S. influence.

Here is how the events unfolded based on the discussion above.

Assassinations of global leaders is right out of CIA's playbook. You can read this for more information.

Now let us turn to current times. A scenario that could have played very similarly to what happened on the night of October 10th, 1966.

Was SCO Summit Modi's "Tashkent" moment?

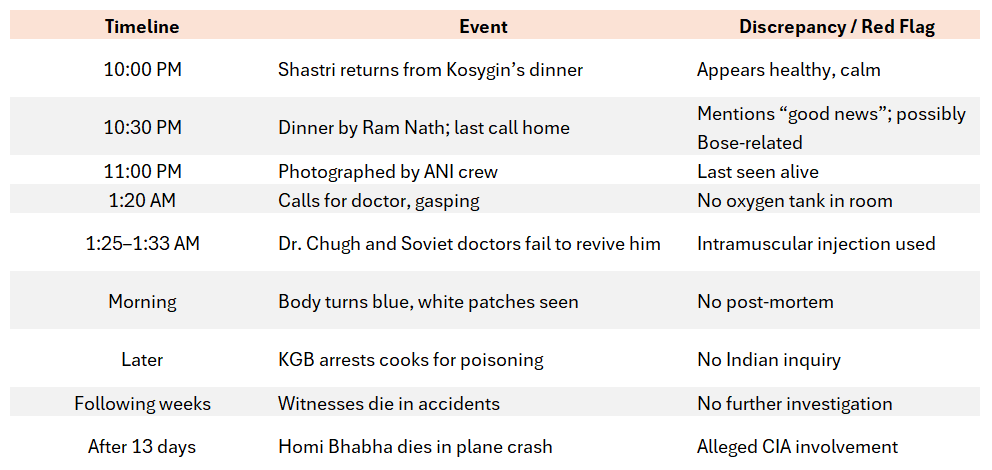

We all remember this interesting quip by PM Modi after his return from the SCO Summit held from Aug 31, 2025 – Sep 1, 2025 in Tianjin.

He said that he returned from the visit to Japan and China the night before, and the audience started clapping. He remarked - "Was the applause for the fact that I went there or that I returned from there?"

When PM Modi made this remark which was seen as a joke, some wondered at the odd sense of humor of a man who is usually quite serious in these matters.

But was it a joke?

Now just look at that one strange set of actions by Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Multiple mainstream sources confirm that Putin personally waited for Modi and insisted on having a private, extended car conversation.

While the idea that Vladimir Putin altered diplomatic protocol to shield Narendra Modi from a potential CIA-backed assassination attempt may sound like the stuff of spy thrillers, history urges caution before dismissing such possibilities outright. In the murky world of intelligence operations, especially involving leaders who disrupt the global balance of power, strategic paranoia is often indistinguishable from prudent statecraft.

Rumors about Western intelligence agencies targeting foreign heads of state are not new. Declassified CIA files from the Cold War reveal detailed blueprints for regime change and assassination attempts against leaders like Fidel Castro, Patrice Lumumba, and even Charles de Gaulle.

The logic was consistent: when a national leader’s ideology or policies threatened the entrenched power matrix dominated by Western alliances, the gloves came off.

Putin, a former KGB officer, understands this world intimately. His mastery of counterintelligence and situational control is legendary. If reports or assessments suggested even a minor anomaly in security arrangements during Modi’s visit, it would not be surprising for him to recalibrate protocol — perhaps altering schedules, travel routes, or even seating arrangements — to mitigate risks.

The Kremlin’s security apparatus is acutely aware of hybrid warfare tactics, which today include not just drones and sabotage, but covert attempts to decapitate leadership or engineer “accidents” under plausible deniability.

The skeptic may rightly argue that such claims lack direct evidence — and indeed, most credible intelligence operations are structured to ensure just that.

However, dismissing the claim entirely ignores decades of documented precedent.

The fact that Putin’s actions deviated from standard protocol lends at least contextual weight to the argument that something was amiss. Whether or not an attempt was truly in motion, the Russian president’s caution underscores a sober truth: in an age of proxy wars, color revolutions, and weaponized diplomacy, leaders like Modi are not merely political figures — they are existential threats to an order long accustomed to control. And in such a theater, even paranoia can be an act of preservation.

The historical pattern, strategic calculus, and documented openness to assassination by Western agencies make the plot against Modi entirely plausible. The protocol breach by Putin is best interpreted as a real-time adaptation to credible intelligence, an act reflective of lessons painfully learned from the avoidable deaths of Shastri and Bhabha.

Putin personally assuming Modi’s protection, and the duration of their stay together, may reflect a real-time response to such specific, credible intelligence. Echoing a “never again” attitude informed by the scars of Tashkent 1966.

Staying Alive to exercise power

I reckon that compelling framework for analyzing political leadership rests on three fundamental imperatives: the ability to win power, the skill to consolidate and continue winning it, and the resilience to survive in order to exercise that power.

This lens offers a sharp perspective on the challenges facing leaders of large, influential nations in the modern era.

- Winning Power: This initial phase requires building a compelling narrative, mobilizing a base, and securing an electoral mandate. In a country as vast and diverse as India, this is a monumental task involving complex social, economic, and political calculations.

- Continuing to Win Power: This is arguably more difficult than the first step. It involves not just governance and policy implementation but also constantly managing public perception, navigating internal party dynamics, and securing re-election. For a leader, this means balancing long-term strategic goals with short-term political necessities.

- Staying Alive to Exercise Power: This can be interpreted both literally and politically.

- Literally: Leaders of major nations face significant security threats, a reality that requires constant vigilance.

- Politically: This involves surviving opposition challenges, media scrutiny, and the immense pressures of the international stage.

When applied to a figure like Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India, the scale of these challenges becomes evident. The initial act of winning power in a democracy as vast and diverse as India is a monumental achievement.

However, the subsequent task of continuing to win, securing repeated electoral mandates while navigating complex internal politics, demonstrates an ability to maintain and grow a base of support through governance and strategic communication.

The third imperative, survival, is perhaps the most demanding. It encompasses not only ensuring physical security but also withstanding immense political pressure, both domestically and internationally. For a leader steering a nation like India, forging an independent foreign policy often means resisting the gravitational pull of established superpowers.

Successfully navigating this path requires a leader to balance national interests against tremendous external pressures. The ability to manage these three domains (winning power, maintaining it, and surviving the geopolitical landscape to wield it effectively) is what ultimately defines a formidable and enduring presence on the world stage.

Independence from Western Hegemony has a price

Independence from American and Western hegemony has often carried a fatal price — a truth etched in the fates of leaders who dared to step outside the orbit of Western control. From Tehran to Kinshasa, Jakarta to Santiago, each story follows a chillingly familiar script: national assertion followed by foreign orchestration, sovereignty answered with subversion.

Mohammad Mossadegh: Iran, 1953: Mossadegh, Iran’s Prime Minister, nationalized the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, seeking economic independence and control over Iran’s oil. This alarmed Britain and the United States.

The CIA and MI6 orchestrated Operation Ajax, a coup that overthrew Mossadegh in August 1953. He was placed under house arrest for life, and the Shah, backed by U.S. support, became increasingly autocratic.

Mohammad Mossadegh became Prime Minister of Iran in 1951 and was hugely popular for taking a stand against the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, a British-owned oil company that had made huge profits while paying Iran only 16% of its profits and often far less. His nationalization efforts led the British government to begin planning to remove him from power. In October 1952, Mosaddegh declared Britain an enemy and cut all diplomatic relations. Britain was unable to resolve the issue unilaterally and looked towards the United States for help. However, the U.S. had opposed British policies; Secretary of State Dean Acheson said the British had “a rule-or-ruin policy in Iran.” That changed after Dwight D. Eisenhower was elected President in 1952. Now, pleas from British intelligence officials and Winston Churchill to oust Mossadegh had a more receptive audience. Beginning in January 1953, the U.S. and the Britain agreed to work together toward Mosaddegh’s removal. (Source: Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training)

Also read this CIA Document.

Patrice Lumumba: Congo, 1961: Patrice Lumumba, Congo’s first democratically elected Prime Minister, demanded true independence from Belgium and criticized Western interference. When Congo descended into crisis, the CIA and Belgian operatives orchestrated a campaign to remove Lumumba, fearing Soviet alignment.

Lumumba was dismissed, captured, tortured, and executed in January 1961, with Western knowledge and involvement.

"...Stuart A. Reid’s “The Lumumba Plot: The Secret History of the CIA and a Cold War Assassination” (Knopf) is that it shows how Congolese independence was never given a chance. Reid is interested not only in how external forces arrayed themselves to bring about a calamity but also in how the personalities of Lumumba, Mobutu, and the separatist leader Moïse Tshombe made finding a solution more difficult." (Source: The New Yorker)

Sukarno: Indonesia, 1965: Sukarno promoted an independent, non-aligned Indonesia, balancing the Communist Party (PKI) and the military. The U.S. grew wary of his leftist leanings. In 1965, following a failed coup blamed on the PKI, the Indonesian military launched a purge with support from U.S. intelligence, resulting in mass killings. Sukarno was forced to hand power to General Suharto and spent his final years under house arrest.

Salvador Allende: Chile, 1973: Allende was elected in 1970 as the world’s first Marxist president through open elections. He nationalized industries and implemented social reforms, drawing hostility from American business interests and the U.S. government. The CIA funded opposition and destabilization efforts. On September 11, 1973, a military coup led by General Pinochet, and aided by U.S. intelligence, overthrew Allende, who died by suicide during the bombardment of the presidential palace.

The pattern is unmistakable: independence from Western diktats is tolerated only until it threatens profit or control. Once defiance emerges, “freedom” becomes treason, and sovereignty becomes a sin punishable by regime change or death. These leaders stood for dignity, not domination—and were destroyed for it. Their stories remain warnings from history: those who walk away from empire must first make peace with peril.

Bagram Airbase Obsession

On September 20th, 2025, US President Donald Trump posted on Truth Social regarding the Bagram Airbase.

The reply from Taliban was not very nice for Trump's ears.

Taliban: We will not give Americans even a grain of our soil. If needed, we will fight them for 20 years again.

They also pointed to the US's own Doha agreement and emphasized their anti-foreign military stance.

That required a spine and some grit.

However, one saw how Pakistan attacked Kabul with airstrikes.

Pakistan’s assault on Afghanistan — striking even in Kabul — after the Taliban openly defied Trump’s warning over the Bagram airbase, lays bare Islamabad’s enduring servitude to Western power centers.

It remains a state for hire, a weaponized proxy willing to shed innocent blood for fleeting rewards — a Western visa, a few dollars, or diplomatic pats on the head.

Quite simply, it’s moral bankruptcy.

Simply put, Pakistan's Army establishment behaves like a prostituting set of mercenaries for the highest price.

They can butcher 25,000 Palestinians in just a couple of nights (Black September 1970 in Jordan, when Zia Ul Haq massacred Palestinians on Jordan's king's orders). They can butcher Balochis.

In 1958, Pakistan military officer Tikka Khan brutally suppressed the first nationalist movement by Baloch people in 1958 and the military commander was dubbed as “Butcher of Balochistan.” (Source: Dhaka Tribune)

They can set events in motion to massacre Afghans in several thousands. That is what Taliban was created to do.

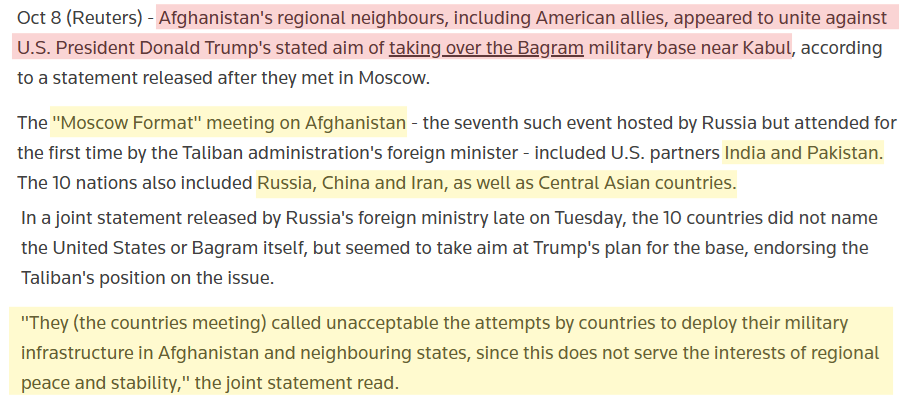

Meanwhile, on October 8th, Russia and 10 nations got together to push back on the Bagram threat by US president Trump.

It was a couple of days after this that Pakistan's jets carried out the airstrikes in Kabul.

Afghanistan's Taliban and Pakistan's Army have been in battles for past few years. But things have escalated recently. Here is a chronology of the battles between the two.

- Apr 16–21, 2022 – Khost & Kunar, Afghanistan

Pakistan carried out airstrikes inside Afghanistan, after Pakistani troops were killed in earlier attacks. Afghan officials reported dozens of civilian deaths; Islamabad did not publicly confirm responsibility. (Source: Al Jazeera) - Dec 11, 2022 – Chaman/Spin Boldak crossing (Kandahar–Balochistan)

Heavy Taliban border-force shelling/gunfire hit Pakistan’s Chaman area after a dispute at the crossing; 7 Pakistani civilians killed, 17 injured (ISPR figures). (Source: The Friday Times) - Dec 15, 2022 – Chaman/Spin Boldak

Fresh cross-border fire the same week left at least 1 dead and 12 injured on the Pakistani side; the crossing shut amid ongoing clashes. (Source: Reuters) - Sept 6–15, 2023 – Torkham (Khyber Pass)

Pakistani and Afghan border guards exchanged fire; the main crossing closed 9 days, stranding thousands of trucks, before reopening after talks. (Source: Reuters) - Aug 13, 2024 – Border area (reported from Kabul)

Clash between Pakistan and Afghan security forces; Kabul said 3 Afghan civilians were killed. (Source: Reuters) - Oct 4–5, 2024 – North Waziristan/Swat (near Afghan border, inside Pakistan)

Militant ambushes & firefights with Pakistani forces; army acknowledged 6 soldiers killed, including a high-ranking officer (see below). These were internal engagements but directly tied to Afghan-based TTP movement across the frontier. (Source: Al Jazeera) - Dec 25, 2024 – Paktika, Afghanistan

Pakistani military airstrikes in eastern Afghanistan reportedly killed at least 46 people (Afghan accounts said mostly civilians). (Source: Reuters) - Feb 21 – Mar 4, 2025 – Torkham

After a dispute over an Afghan outpost, Pakistani and Afghan forces traded fire; at least 1 killed, several injured; crossing closed ~10 days during Ramadan before tensions eased. (Source: Reuters) - Oct 7–8, 2025 – Orakzai, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (near Afghan border)

Large firefight during a Pakistani raid on a TTP hideout: 11 Pakistani soldiers killed (including a Lt Col and a Major), 19 militants killed. Islamabad links such cells to Afghan sanctuaries. (Source: AP) - Oct 10, 2025 – Kabul & border tension

Taliban authorities accused Pakistan of fresh airstrikes inside Afghanistan and warned of consequences; Islamabad said it would act against militants. (Ongoing claims/counterclaims). (Source: The Times of India)

The Afghanistan–Pakistan relationship has descended into a pattern of mistrust, militarized border clashes, and collective punishment of civilians — a cycle that now risks open confrontation.

The chronology of the past three years shows a sharp escalation from localized skirmishes to direct airstrikes and sustained hostilities. Pakistan’s incursions into Khost, Kunar, and later Paktika — often justified as anti-TTP operations — have killed scores of Afghan civilians and hardened Taliban resolve. Meanwhile, Afghan border forces have repeatedly targeted Pakistani positions at crossings like Chaman, Torkham, and Spin Boldak, paralyzing trade and deepening economic pain on both sides.

What began as border friction is morphing into a proxy conflict between two militarized, distrustful neighbors — one seeking legitimacy through defiance, the other through dominance.

Strategically, the Taliban no longer view Pakistan as their benefactor but as a rival seeking to undermine Afghan sovereignty. Islamabad’s reliance on force, coupled with its internal instability, makes sustained engagement untenable. The trajectory now points toward an entrenched cold war along the Durand Line — marked by sporadic clashes, airstrikes, and retaliatory sabotage — rather than reconciliation. Both sides are arming for a long struggle in which the real victims will be border communities, and the outcome could redefine South Asia’s security architecture for decades to come.

Why is Bagram important?

Bagram Air Base, situated in Afghanistan’s Parwan province about 40–60 kilometers north of Kabul, occupies one of the most strategically significant locations in the region. Its geography allows access to the country’s central and northern corridors, making it a vital node for both military and logistical operations. The base boasts a massive 11,800-foot (approximately 3,600-meter) runway, capable of accommodating heavy cargo planes and advanced combat aircraft, providing unmatched operational flexibility.

During the two decades of U.S. presence, Bagram served as the principal hub for air operations, intelligence gathering, logistics, and counterterrorism missions across Afghanistan and into Central Asia. It became the heart of America’s military infrastructure in the region, facilitating rapid deployment, aerial surveillance, and coordination of special operations.

Strategically, Bagram’s location near the Chinese border region of Xinjiang adds to its enduring geopolitical importance. For U.S. defense planners, the base represents not only a launch point for operations in Afghanistan but also a potential forward platform for monitoring developments in western China, Central Asia, and even parts of Iran. Advocates for reclaiming the base see it as a crucial vantage point in the emerging great-power rivalry, enabling the United States to maintain surveillance capabilities and project influence deep into Eurasia.

Bagram provides a strategic fulcrum that can redefine regional power dynamics, offering whoever controls it a commanding position at the crossroads of South Asia, Central Asia, and China’s western frontier.

If U.S.-Pakistan cooperation is central to the Bagram arrangement, India may see that as an encirclement: U.S. presence plus Pakistani ground access could edge India out of some influence in Afghanistan and jeopardize it's investment in Chabahar in Iran.

India will then be forced to strengthen its own ties with Iran (Chabahar), Central Asian states, or investing more heavily in alternative corridors (north-south networks, Central Asia – e.g. via Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, etc.).

The Lantern of Freedom

Remember one thing clearly -

The tale of Lal Bahadur Shastri’s quiet courage and mysterious death, followed by Homi Bhabha’s fatal fall, was not an isolated tragedy — it was a chapter in a larger play of power, where independence is often punished by those who preach it loudest.

India’s story since then has been that of a nation learning to hold its lantern against the storm.

Every leader who tried to assert India’s strategic autonomy — from Indira Gandhi after 1971 to Atal Bihari Vajpayee after Pokhran, and now Narendra Modi — has faced invisible headwinds from a world order intolerant of those who refuse to bow.

The West’s vocabulary for “freedom” has often meant obedience dressed as partnership; its rhetoric about “democracy” has masked the fear of a civilization thinking for itself.

Yet India’s strength has always been its quiet endurance — its ability to look within when others seek validation abroad.

Today, as Bagram, Chabahar, and the new Eurasian corridors redefine the global chessboard, India stands again at that eternal crossroad between cooperation and control.

Comments ()