What Do NGOs Really Deliver for India?

India has more NGOs per capita than policemen. They get lakhs of crores in funding. For all that, what do they really deliver for India? Contrast to spiritual organizations which use a radically different social work paradigm. They deliver at scale. How? Why? It is time to rethink.

When the Gates Open...

A traveler once came to a drought-struck city where people argued about water the way merchants argue about gold.

In the square, three crowds had gathered.

The first crowd carried banners. They shouted the names of rivers and laws. They held meetings under a tin roof and issued statements that sounded like rain but did not wet the earth. “We have raised awareness,” they said, and the people clapped because the words were polished.

The second crowd carried ledgers. They spoke softly, like bankers. “We have funds,” they said. “We will commission studies. We will file petitions. We will build capacity.” They hired scribes to write thick reports. The reports smelled of fresh ink, and the people clapped because the paper looked like progress.

The third crowd carried tools. They did not shout. They did not distribute pamphlets. They walked past the square toward the broken canal.

The traveler followed them.

He found an old channel, cracked like a dry tongue. Grass had grown where water was meant to run. There were places where the embankment had collapsed, places where careless seasons had carved small defeats into big failures. Men sat on stones and spoke of promises made by governments long ago. “This canal was meant to feed a city,” they said. “Now it feeds dust.”

Among the tool-carriers was a quiet man in a simple robe. He did not introduce himself as a savior. He did not ask for applause. He only looked at the canal the way a physician looks at a pulse—without drama, but with full attention.

The engineer beside him unfolded maps. The worker beside him sharpened a spade. The quiet man said one sentence:

“Water does not need speeches. It needs a path.”

That night, the work began.

No one put up a stage. No one invited cameras. No one demanded a certificate of virtue. The canal was measured, the weak sections marked, the erosion corrected, the embankments strengthened, and escape structures built so floods would not destroy what discipline repaired. The traveler saw men working as if time itself were on a deadline. Four thousand hands, sixteen months, day and night—like a mantra repeated until it becomes real.

In the square, the first crowd still shouted. The second crowd still counted. But the third crowd kept digging.

When the gates finally opened, something strange happened.

The water did not travel with fanfare. It moved the way truth moves—fast, quiet, unstoppable once the route is clear. It reached the reservoir in days, not weeks. The city that had learned to live with dry taps felt a primitive relief: the relief of seeing an empty vessel fill.

The traveler returned to the square. The banner-holders claimed a victory of “public pressure.” The ledger-holders said, “This is proof that our model works.” Each crowd tried to place the water inside its own narrative, like men trying to trap a river in a jar.

But the traveler noticed something else.

He saw the tool-carriers leaving the city before anyone could garland them. They were already walking toward other thirsty lands—places where fluoride turned water into slow poison, places where villages carried buckets like burdens, places where terrain itself resisted pipelines. And yet, the same thing happened again and again: pipes laid across long distances, tanks built, purification systems installed, villages drinking clean water like a forgotten blessing returning.

One evening, the traveler found the quiet man sitting alone near a newly built tank, watching a child drink.

The traveler asked, “Why do you not announce what you have done? Why do you not tell the world?”

The quiet man picked up a small clay cup. It had a crack.

He poured water into it. The water leaked out.

Then he placed a finger on the crack and poured again. The cup filled.

He said, “If your cup is cracked, would you organize a conference on hydration? Or would you seal the crack?”

The traveler, embarrassed, tried to defend the other crowds. “But awareness matters. Policy matters. Advocacy matters.”

The quiet man nodded. “Yes. But tell me: when a man is thirsty, do you give him a slogan… or a sip?”

The traveler was silent.

The quiet man continued, “There are two kinds of service. One wants to be seen doing good. The other wants good to be done. The first builds stages. The second builds channels.”

The traveler thought of the reports he had seen—beautiful, thick, fluent. He thought of the money he had heard about—vast sums moving through sophisticated structures. He thought of how easily virtue can become an industry, how easily ‘help’ can become a lever, how easily a sector can sit in the sweet spot—private, tax-advantaged, politically active—without the discipline that binds corporations or the accountability that binds states.

He asked the question that had brought him to this city: “Then how does a nation know who truly serves it?”

The quiet man pointed to the tank.

“Do not ask the servant. Ask the water.”

The traveler looked.

He saw women no longer walking miles for a pot. He saw children drinking without fear. He saw farmers looking at their soil differently because trees had returned to the land and shade had begun to soften the sun’s cruelty. He saw a river basin changing slowly, not in speeches but in roots.

He returned to the square one last time. The crowds were still there. Their banners were brighter, their brochures glossier, their language more refined.

But now he noticed the simplest test.

He walked to the edge of the city where the canal ran.

He listened.

He did not hear slogans.

He heard water.

And he understood the Zen of it:

A society is not healed by those who describe suffering best.

It is healed by those who quietly remove its causes.

A river does not ask who funded its flow.

A child does not care whose ideology purified the cup.

Only this matters:

When the gates open - does water arrive?

SUPPORT DRISHTIKONE

In an increasingly complex and shifting world, thoughtful analysis is rare and essential. At Drishtikone, we dedicate hundreds of dollars and hours each month to producing deep, independent insights on geopolitics, culture, and global trends. Our work is rigorous, fearless, and free from advertising and external influence, sustained solely by the support of readers like you. For over two decades, Drishtikone has remained a one-person labor of commitment: no staff, no corporate funding — just a deep belief in the importance of perspective, truth, and analysis. If our work helps you better understand the forces shaping our world, we invite you to support it with your contribution by subscribing to the paid version or a one-time gift. Your support directly fuels independent thinking. To contribute, choose the USD equivalent amount you are comfortable with in your own currency. You can head to the Contribute page and use Stripe or PayPal to make a contribution.

Sri Sathya Sai Baba's Water

In the early 2000s, Sathya Sai Baba accomplished something that had eluded successive governments for decades: he helped resolve a water crisis that had haunted Chennai for over a century.

Chennai, often called India’s “Detroit of Asia,” once struggled to survive on barely 250 million liters of water per day against a requirement of nearly 750 million. Entire neighborhoods went without supply for days during peak summer. The ambitious Telugu Ganga Project—designed to bring 15 TMC of water from the Krishna River to the city—had deteriorated over time. Seepage, erosion, and neglect reduced actual inflow to a fraction of the promised amount. The canal lay damaged. The reservoirs ran low. The city’s thirst deepened.

On 19 January 2002, Sathya Sai Baba announced that the Sri Sathya Sai Central Trust would intervene. There were no protests, no political campaigns, no international appeals. Only a commitment to execute.

Within sixteen months, working round the clock with nearly 4,000 laborers, the Trust rehabilitated 65 kilometers of the Kandaleru-Poondi canal, strengthened embankments, constructed flood escape structures, and enhanced reservoir capacity. Modern engineering replaced decay. When the gates opened on 23 November 2004, water covered 150 kilometers in just four days—nearly half the previous transit time. The Poondi reservoir is filled.

Chennai found relief. In recognition, the Andhra Pradesh government rechristened the canal “Sathya Sai Ganga.”

There was no foreign funding. No global publicity campaign. Just delivery.

And this was not an isolated intervention.

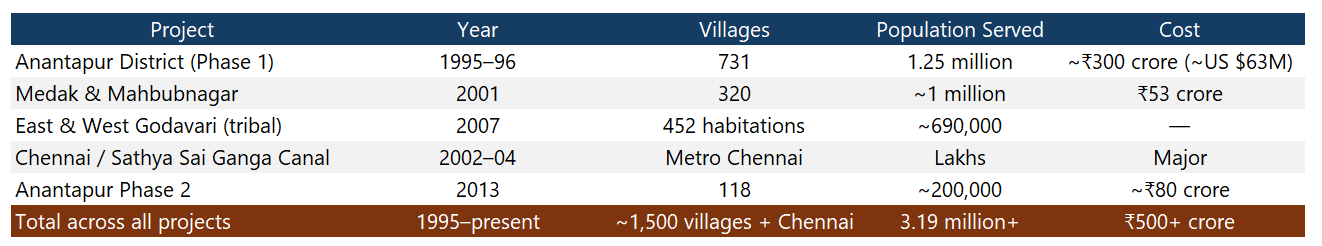

Years earlier, in drought-stricken Anantapur—where fluoride-laced groundwater caused deformities and disease—the Trust funded a massive drinking water project. Over 2,000 kilometers of pipeline were laid. Hundreds of reservoirs, tanks, and cisterns were constructed. In roughly 18 months, 731 villages received safe water. The Government of India formally acknowledged it as an unparalleled private initiative executed without state budgetary support.

Similar infrastructure projects followed in Medak and Mahabubnagar. In East and West Godavari districts, river-based supply systems benefited nearly 700,000 people. In Paderu’s tribal belt, pipelines were laid across rugged terrain to serve 350 villages. In Kerala, filtration units now provide clean water daily to over 165,000 citizens.

By 2020, the Sri Sathya Sai National Drinking Water Mission had installed purification systems across multiple states, addressing fluoride, arsenic, and heavy metal contamination affecting millions.

So what was delivered?

The Trust executed what the Government of India's own Ninth Five-Year Plan document called "an unparalleled example of private initiative" — the largest drinking water project ever completed by a non-government organization anywhere in the world:

The Chennai project rebuilt the Telugu Ganga Canal to ensure Krishna river water supply to the city, benefiting lakhs of urban residents. This is registered with the United Nations SDG Partnership Platform as a model project.

This is not boutique charity. It is infrastructure. It is public health intervention. It is civil engineering on a regional scale.

The work continues to flow, quietly—much like the water itself.

Rivers and Soil from Isha

Isha Foundation's ecological work operates at a genuinely continental scale:

Rally for Rivers (2017): Mobilized 160 million people in a national awareness campaign. Produced a detailed policy recommendation document for river revitalization. Six states — Karnataka, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Punjab, Assam, and Chhattisgarh — signed MoUs with Isha for river revitalization programs. The Central Government issued an advisory to all state governments based on Rally for Rivers principles, and NITI Aayog set up a committee under its CEO to examine the policy proposal.

Cauvery Calling: As of mid-2025, 12.2 crore (122 million) living trees have been planted across 34,000 acres in the Cauvery basin, with 2.38 lakh farmers shifted to tree-based agroforestry. The program is accredited by UNEP, UNCCD, and is a member of IUCN. The long-term goal is 242 crore trees to increase water retention by 12 trillion liters in the Cauvery basin and revive river flow to historical levels. Farmer incomes under the agroforestry model have increased 300–800% over 5–7 years.

The Cauvery Calling movement, launched by spiritual leader and environmentalist Sadhguru, has planted 1.36 crore saplings across 34,000 acres in the Cauvery River basin during the 2024-25 season. With this, the total number of saplings planted under the campaign has reached a remarkable 12.2 crore. The initiative has helped 2.38 lakh farmers shift to tree-based agriculture, which improves soil health, increases water retention, and boosts farm income. (Source: "Sadhguru's Cauvery Calling plants 1.36 cr trees in 2024-25, celebrates World Environment Day with 12.2 cr milestone" / Asianet)

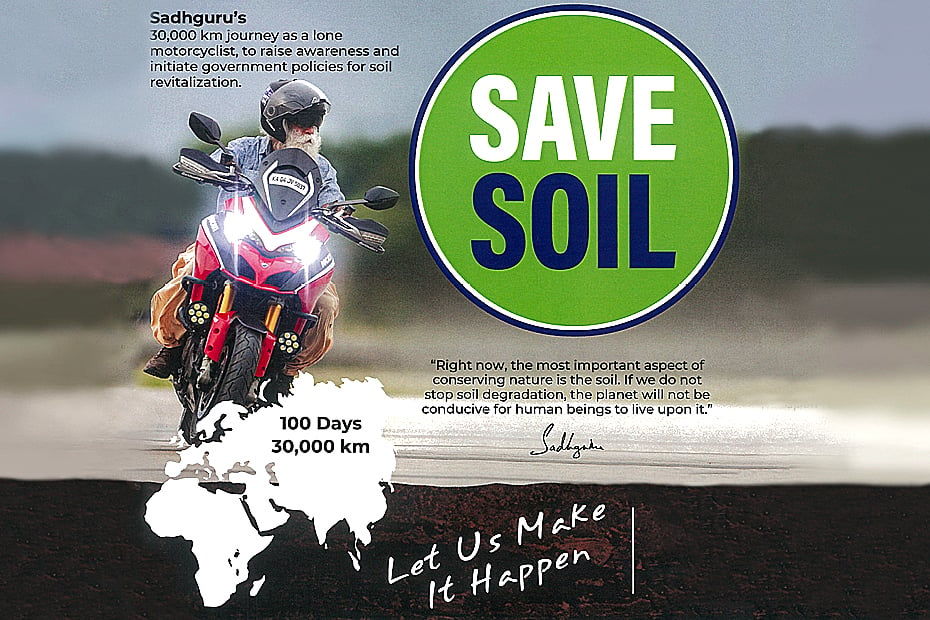

And then there is the humongous Save Soil campaign by Sadhguru and Isha Foundation.

Save Soil Campaign

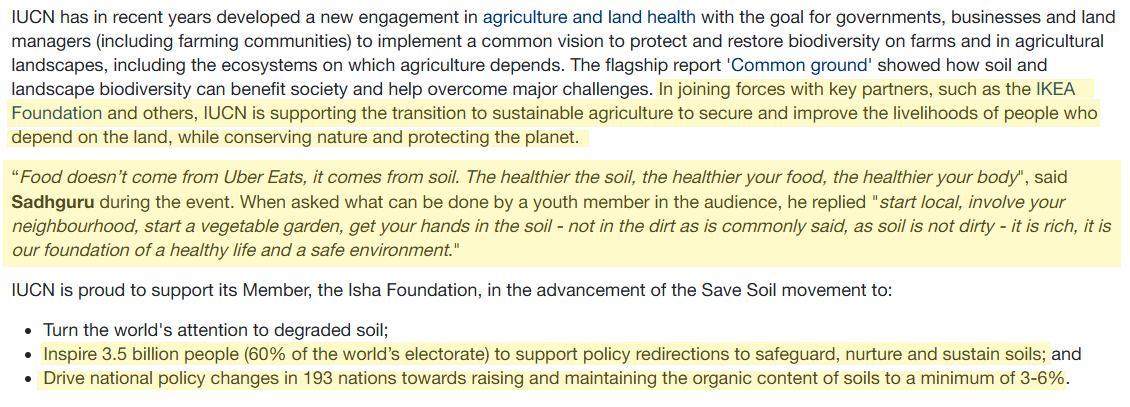

The Conscious Planet – Save Soil movement, envisioned by Sadhguru, is a global campaign to address accelerating soil degradation by pushing governments to adopt policies that ensure at least 3–6% organic content in agricultural soils. Launched in 2022 with UN-linked events in Geneva, it is supported or partnered by bodies such as UNCCD, WFP, UNEP, IUCN and others, framing soil health as central to food security, climate stability and biodiversity.

The 30,000 km motorcycle journey: To turn a technical issue into a mass movement, Sadhguru undertook a 100‑day, 30,000 km solo motorcycle ride starting from Trafalgar Square, London, in March 2022, traveling across 27 countries in Europe, the Middle East, Central Asia, and India.

At over 600 public events and media interactions, he called on citizens to demand soil‑friendly policies and met political leaders, scientists, and influencers to translate public enthusiasm into governance commitments.

One often wonders - did he have time to even sleep? One man at 68 years was doing all this. For what?! To wake people up? Can you do that even if you were given a trillion dollars?

From awareness to policy and government uptake: Save Soil’s central demand is that nations legislate to maintain 3–6% organic matter in their cultivable soils, using incentives, long‑term soil management plans and farmer‑centric schemes. By mid‑2023, various reports note that 70‑plus countries had issued written or verbal support, with around 74–81 nations and several Indian states signing MoUs or policy intent documents related to soil health. Examples include MoUs with the International Center for Biosaline Agriculture in the UAE, seven Caribbean nations, Azerbaijan and Romania, as well as alignment with France’s “4 per 1000” soil‑carbon initiative. The Commonwealth, the European Union and pan‑European organizations publicly expressed support, while the EU’s emerging Soil Health Law is often discussed in the same policy space as global soil‑awareness drives like Save Soil, indicating how such campaigns help create political momentum even when laws are not formally branded under the movement.

Legacy and resources: International organizations such as IUCN describe Save Soil as a movement aiming to mobilize 3.5 billion people—about 60% of the world’s electorate—to demand soil‑centric policies. Analyses note that its biggest achievement so far is moving soil from a niche technical concern into mainstream political and media discourse, even as critics argue that stronger binding targets and accountability are needed to convert promises into on‑ground transformation.

Now let us go to the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh.

Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS): Seva and Brickbats

Seva Bharati and Sewa networks: RSS‑inspired Seva Bharati/Rashtriya Sewa Bharati reportedly supports over 35,000 projects focused on the urban poor, slum communities and tribal areas, running libraries, tuition centers, clinics, blood banks and hostels. Their own data claims roughly 12,000 programmes each in education and health, plus more than 11,000 social‑work projects and 6,700+ skill‑development initiatives aimed at employability and self‑reliance.

Social harmony and tribal outreach: RSS positions seva as part of “samarasata” (social harmony), with Samskar Kendras, rural‑development work, cultural programs and conflict‑resolution efforts in sensitive areas like Assam, Manipur and tribal belts to integrate marginalized communities into the broader social fabric.

Disaster relief and community mediation: RSS and its affiliates often mobilize volunteers and logistics during riots, floods and earthquakes, and local units have acted as mediators in communal or ethnic tensions, emphasizing on-the-ground contact rather than only legal‑political mechanisms.

Mata Amritanandamayi’s organizations at scale

Institutional ecosystem: Mata Amritanandamayi Math (MAM) and the related Mata Amritanandamayi Mission Trust run the multi‑campus Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham university and about 90 Amrita Vidyalayam schools, along with hospitals and community centers serving largely low‑income populations.

Disaster relief and housing: After the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, the Math committed around 46 million USD in relief, including 6,200 houses in India and Sri Lanka and 700 fishing boats; it has also contributed major funds and aid for disasters like Haiti 2010, Hurricane Katrina and the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake.

Pensions, villages and self‑help groups: Programs like Amrita Nidhi provide lifetime monthly pensions to about 50,000 widows and disabled people, with a stated target of 100,000 beneficiaries. Amrita SeRVe has “adopted” 101 villages for integrated development across health, education, water/sanitation, agriculture, eco‑infrastructure, income generation and self‑empowerment, while Amrita SREE fosters women’s self‑help groups and vocational training to curb farmer distress and suicides.

Global “Embracing the World” network: Under the banner “Embracing the World,” MAM coordinates international projects in food, shelter, healthcare, education and livelihood, including environmental work, river‑cleanup funding (e.g., major contributions to Namami Gange and Kerala sanitation) and prison‑outreach programs.

Taking Stock

Today, we need to take stock — calmly, honestly, without rhetoric — of what individual and non-government efforts actually deliver for the nation.

Over the past decades, NGOs in India have received enormous funding, built global networks, partnered with international institutions, and positioned themselves as moral custodians of development. They influence narratives, shape policy discussions, and often speak in the name of the vulnerable. But a simple question demands clarity: What do they concretely deliver for India and Indians?

Is their work transformative at scale? Or is it boutique — limited pilots, carefully curated case studies, and impact reports written in fluent development language but thin in measurable national change?

These questions are not cynical. They are necessary.

When public money, foreign grants, and philanthropic capital flow into a sector, citizens have a right to ask: What has changed structurally? Where are the large-scale, durable solutions? How many millions were reached — not in brochures, but in verifiable numbers?

In contrast, certain spiritual organizations in India have demonstrated an ability to execute infrastructure-scale interventions — water projects, rural transformation, healthcare networks — often without global advocacy ecosystems or aggressive self-promotion. Their work tends to be tangible: reservoirs filled, villages supplied, hospitals built, green cover increased, and rivers improved.

This is not about praise or blame. It is about accountability.

If India is to mature as a civilizational state, it must evaluate outcomes, not optics; scale, not storytelling.

The question remains open — and it deserves serious, data-driven answers.

The Scale and the Mechanisms

As per the Federal Reserve’s Financial Accounts (Z.1) data available through FRED, total assets held by U.S. nonprofit organizations stood at roughly $13.40 trillion in Q2 2025.

To put that into perspective: that is larger than the combined 2025 GDP of Japan, Germany, and India.

That scale matters.

And remember this is just in the United States!!

Of course, this is not an argument against charity. Many charitable organizations in India and elsewhere do meaningful, direct, ground-level work — feeding people, running schools, offering disaster relief, providing healthcare. That kind of intervention has clear social value.

The issue is structural.

A legal architecture originally designed to enable modest, community-oriented charities now encompasses massive universities, hospital systems, philanthropic foundations, endowments, and advocacy institutions that manage portfolios rivaling those of sovereign wealth funds.

If a corporation commanded that level of capital, it would operate under stringent disclosure rules, market scrutiny, taxation regimes, and regulatory oversight.

If a state wielded comparable economic weight, it would face elections, constitutional constraints, and public accountability.

But the modern nonprofit sector occupies an unusual position. It is private. It is largely tax-exempt. And it is often politically engaged.

That asymmetry deserves examination.

In today’s ecosystem, NGOs are not merely service providers; many function as sophisticated political actors. Funds move across linked legal structures — in the United States, for example, between 501(c)(3) and 501(c)(4) entities — enabling litigation strategies, policy advocacy, lobbying, and coordinated public-pressure campaigns.

The largest flows of money in the sector increasingly fund narrative shaping, regulatory intervention, and ideological influence — not direct relief.

This raises serious questions:

- Who defines the mandate?

- Who sets the agenda?

- Who benefits from the policy shifts they pursue?

- And what mechanisms of democratic accountability apply when vast, tax-advantaged capital is deployed to influence public life across borders?

A sector sitting on $13+ trillion in assets cannot be treated as marginal. It is an economic power center — operating in a regulatory and political grey zone.

That reality does not condemn all nonprofits. But it does demand clearer scrutiny, sharper transparency standards, and a more honest public conversation about scale, influence, and accountability.

But is it there?

On the other hand, the unscrupulous have made it into a framework. A framework of intervention, subversion and attack.

Take a listen.

This makes one think. Doesn't it?

Delivering 'Social Work' - How and Why?

Doing good for those who cannot lift themselves up is often rooted in a powerful assumption: that those with wealth, education, and influence can correct what destiny has denied others. It is a noble impulse.

Across the world, this impulse has institutionalized itself into charity and non-governmental organizations.

To understand the contrast, consider a revealing episode involving Swami Vivekananda and John D. Rockefeller.

In 1894, Rockefeller — already one of the richest men in America — sought out Vivekananda, the Indian monk who had electrified Western audiences. When they met, Vivekananda reportedly asked him a piercing question: if you possess vastly more wealth than others, does that mean you are proportionately wiser? Perhaps, he suggested, wealth makes one an instrument — not an owner. Perhaps some of it must flow back to society.

Rockefeller was not pleased. He left without gratitude. Yet within a week, he returned, placing before Vivekananda a document describing a charitable donation.

“You must thank me,” he reportedly said. Vivekananda calmly replied, “It is you who must thank me.” Rockefeller soon left.

That donation would eventually grow into the Rockefeller Foundation.

Rockefeller went on to take over the world of medicine and food in a way that the entire humanity has been caged in the web of chemicals.

History, however, shows that philanthropy can coexist with power consolidation. Foundations have sometimes shaped medicine, agriculture, and policy in ways aligned with broader strategic interests. Charity can become a mandate — an instrument of influence, structured from the top down.

In contrast, the Ramakrishna Mission, founded by Vivekananda in 1897, emerged from devotion rather than corporate architecture. Its schools, hospitals, disaster relief, and rural development efforts were not extensions of a geopolitical design. They were expressions of spiritual duty. Service was not branding; it was worship.

So let us distill the lessons from above.

We see two paradigms of organized social work.

Work as Mandate: structured, professionalized, often well-funded. It may produce scale, policy reach, and global networks. But it can also embed agendas — shaping beneficiaries according to ideological frameworks or donor priorities.

Work as Devotion: rooted in humility before the Divine or Guru. It sees the recipient not as a project but as sacred. Its legitimacy flows from sacrifice, not authority.

Both paradigms attract talented people. Both can produce meaningful outcomes, though the former are increasingly doing lesser than their weight, power and money.

The question we believe is not of competence. It is of orientation.

Mandate asks: What shall we do for them?

Devotion asks: How shall we serve?

The difference influences quality, trust, and long-term impact. When service is offered as devotion, it often scales quietly, sustained by faith rather than funding cycles. When service is driven by mandate, it scales visibly, sustained by capital and compliance structures.

In the end, societies must ask: which framework produces empowerment without dependency, dignity without design, and service without hidden strings?

The answer determines not just results — but the soul of social work itself.

NGOs in India - Scale sans Accountability

The proliferation of NGOs in India is not anecdotal. It is structural. It is statistical. And it demands serious scrutiny.

By 2010–11, India was receiving over $2 billion annually in foreign contributions to NGOs. Roughly 33% of that money came from the United States alone. That year, about 22,000 NGOs received more than $2 billion from abroad, with approximately $650 million sourced from the US.

Pause and absorb that number.

India was witnessing what newspapers described as an “NGO boom.” Estimates suggested there was one NGO for every 600 Indians. Other assessments placed it closer to 1 NGO per 400 citizens.

Government data indicates there are approximately 3.3 million registered NGOs in the country in 2009.

The term “civil society” is not commonly used in India, though its usage has gained traction in the media in recent years. More commonly, Indian civil society is referred to as the voluntary sector or as non-governmental organizations (NGOs). According to the Central Statistical Institute, there were 3.3 million NGOs registered in India as of 2009—roughly one for every 400 citizens. As of 2020, GuideStar India listed more than 10,000 verified NGOs and 1,600 certified NGOs, while 143,946 NGOs were registered on the NGO Darpan’ Portal of Nitti Aayog. (Source: Civic Freedom Monitor-India / International Center for Not-for-Profit Law)

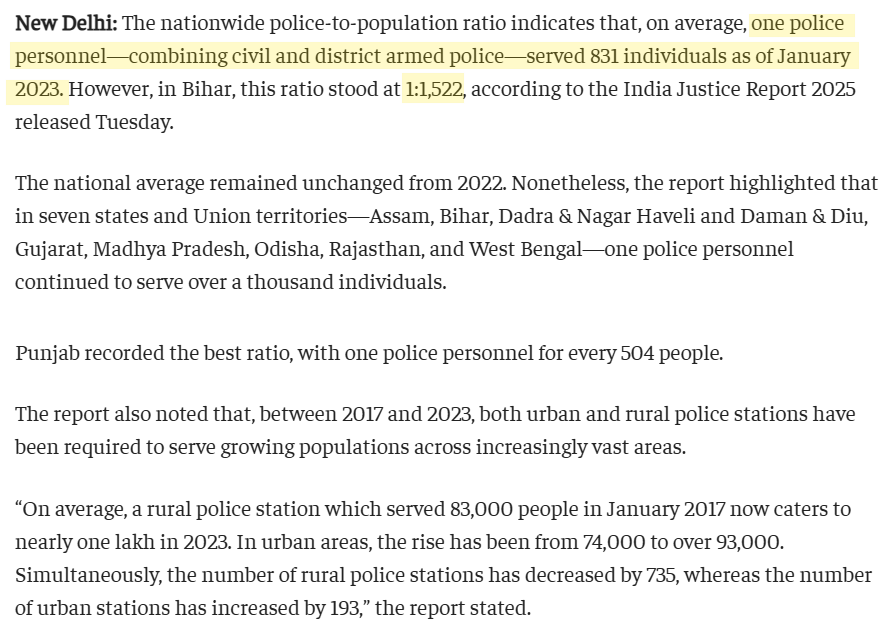

By contrast, India has one policeman per 831 people.

Let that comparison sink in.

There were more NGOs per capita than law enforcement personnel.

The Central Bureau of Investigation submitted an affidavit in 2015 stating there were over 31 lakh NGOs across 26 states, excluding additional figures from certain states and Union Territories. Add those, and the number climbs even higher. For perspective: India had around 15 lakh schools in 2011 and just under 12,000 government hospitals nationwide. The NGO count surpassed both schools and hospitals — and exceeded the actual strength of policemen, which stood at approximately 17.3 lakh in 2014 against a sanctioned strength of 21 lakh.

The Central Bureau of Investigation, in an affidavit filed in the Supreme Court in August 2015, said that there were 31 lakh NGOs in 26 States of India. Karnataka, Odisha and Telangana are still to adduce information about the number of NGOs, so the country-total will be more than 31 lakhs. Besides, more than 82,000 NGOs are registered in the seven Union Territories. The total number of schools in the country is around 15 lakh, as per data compiled by the Planning Commission in 2011. The Commission had calculated the number of schools, classifying them as primary, upper primary, secondary, lower secondary and higher secondary. In March 2011, the total number of Government hospitals in the country was 11,993, with 7.84 lakh beds. Of these, 7,347 hospitals were in rural areas with 1.60 lakh beds and 4,146 hospitals in urban areas with 6.18 lakh beds. The number of NGOs also exceeds the strength of policemen in the country. According to the National Crime Records Bureau, there were 17.3 lakh policemen nationwide in 2014, as against a sanctioned strength of 21 lakh. (Source)

This scale is extraordinary.

Now consider funding flows. In one parliamentary response, the Union Ministry of Home Affairs noted that Rs 13,051 crore in foreign contributions were donated to over 17,000 NGOs in a recent period. In 2012–13 alone, more than Rs 11,500 crore flowed to over 20,000 NGOs.

Indeed, running an NGO has become big business and many people live off it, while the cause for which they raise money through the NGO is ignored. The Union Minister of State for Home Affairs, while replying to a question in Parliament, noted that foreign contributions totaling Rs13,051 crore were donated to 17,616 NGOs recently. In 2012-2013, Rs11,527 crore donations were made to 20,497 NGOs. (Source)

When money of this magnitude moves through lightly scrutinized channels, risk follows.

This is not a blanket indictment of all NGOs. Many do sincere work. But proliferation without accountability creates vulnerability — to fraud, to money laundering, to ideological manipulation, and in some cases, to outright criminality.

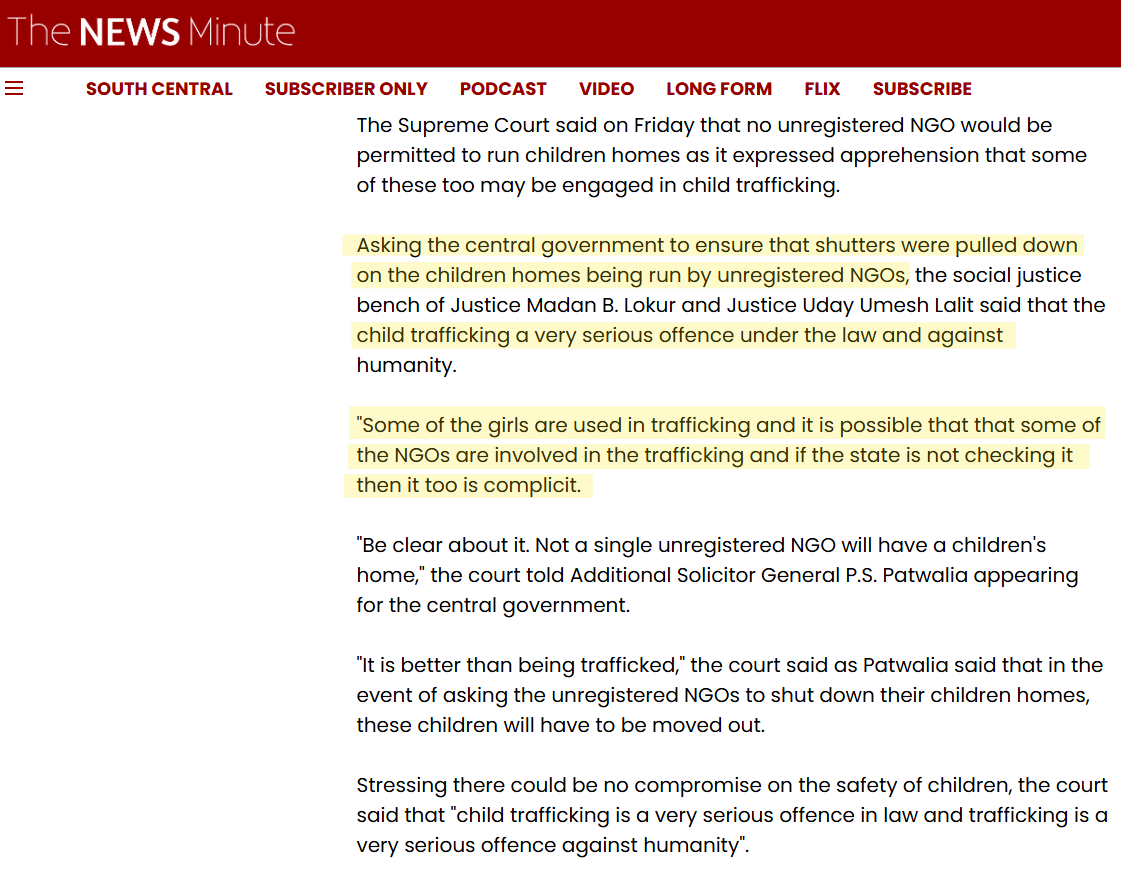

The courts have not been blind to this reality.

In 2013, the Delhi High Court made scathing observations while hearing a case related to children’s institutions. A bench led by Justice Pradeep Nandrajog remarked that “99% of NGOs are fraud and merely money-making devices,” and called for tougher licensing norms. The remarks came in the context of child homes operating without proper compliance — a sector particularly vulnerable to abuse.

The Delhi high court has called for toughening of licensing norms for NGOs observing that 99% of them are "fraud" and "merely money-making devices" "Most private run so called philanthropic organizations do not understand their social responsibilities. 99% of the existing NGOs are fraud and simply moneymaking devices. Only one out of every hundred NGOs serve the purpose they are set up for", a bench headed by Justice Pradeep Nandrajog said. "There is a need for toughening of licensing norms and legislature has to keep this in mind", the bench said. The stinging remarks came while the court was hearing a petition filed by children homes Chatravas and Arya orphanage challenging government's refusal to grant them license under the Women and Children's Institutions (Licensing) Act, 1956 and insisting on registration under the Juvenile Justice Act. (Source)

In 2015, the Supreme Court ordered that no unregistered NGO should be allowed to take custody of children. The deadline was clear: shut down unregistered homes. Investigations revealed that some so-called children’s homes had become trafficking hubs. One may think this was mere bureaucratic non-compliance. But it is far more! It is criminal betrayal.

In 2020, a government audit team — comprising students from premier institutions such as IITs and TISS — inspected NGOs operating under a ministry managing old-age homes, SC hostels, and de-addiction centers. Out of 1,233 NGOs inspected, 266 were found woefully inadequate or outright fraudulent. In some categories, 20–23% of NGOs were non-functional. Grants were canceled. Blacklists issued.

Sources said the 266 NGOs have been given show-cause notice to clarify on the audit findings and their grants are being cancelled. The institutions found to be indulging in grave irregularities are even being blacklisted, which means they will not be eligible in future for government contracts. Of the total 1,233 NGOs inspected, 164 are associated with "schools/hostels for SCs" of which 44 were found to be non-functional. Out of the 523 NGOs working in the running of senior citizen homes, 120 were detected as non-functional, which is roughly 23%. Around 18% or 102 NGOs of the 589 associated with de-addiction centres were found to be non-functional. (Source)

If a private company had one-fifth of its branches non-functional while continuing to draw funding, it would collapse under regulatory action.

Yet the NGO sector often escapes sustained structural reform.

Why?

Because NGOs operate in a moral halo. They are presumed virtuous. Questioning them risks being labeled anti-civil society or anti-humanitarian. But mature democracies must separate intent from impact.

The danger is not merely financial leakage. It is strategic exposure.

When millions of dollars flow from foreign sources into a country with minimal real-time transparency, questions of influence arise. Who shapes the agenda? Who sets the narratives? Who decides which social fractures deserve amplification? NGOs can be vehicles for service — but they can also become conduits for ideological export, policy pressure, and institutional subversion.

The problem is not that NGOs exist.

The problem is scale without scrutiny.

Three million organizations cannot all be effectively monitored. Certification often rests on district-level verification. Annual filings are frequently delayed or incomplete. Audits are episodic, not systemic. Meanwhile, public perception continues to assume that registered status equals integrity.

That assumption is dangerous.

India must distinguish between:

- Genuine service organizations delivering measurable outcomes

- Advocacy bodies pursuing ideological agendas

- Shell entities designed for grant extraction

- Criminal fronts exploiting vulnerable populations

Transparency is not hostility. It is hygiene.

If there are more NGOs than schools, more NGOs than hospitals, and more NGOs per capita than policemen, then accountability mechanisms must scale accordingly. Every rupee raised in the name of the poor must be traceable. Every foreign contribution must be transparent. Every child in institutional care must be protected by enforceable compliance standards.

Civil society is essential to democracy. But civil society without accountability becomes a shadow state.

And shadow states are not philanthropic. They are political.

India’s NGO explosion is real. Its funding scale is massive. Its oversight remains uneven.

The question is no longer whether reform is needed.

The question is whether the nation has the will to demand it.

The Humongous Funding

We have already discussed how India has one of the largest non-profit sectors on earth with roughly one NGO for every 400 Indians — far outnumbering the country's schools, hospitals, and police stations combined.

Where does the funding come from?

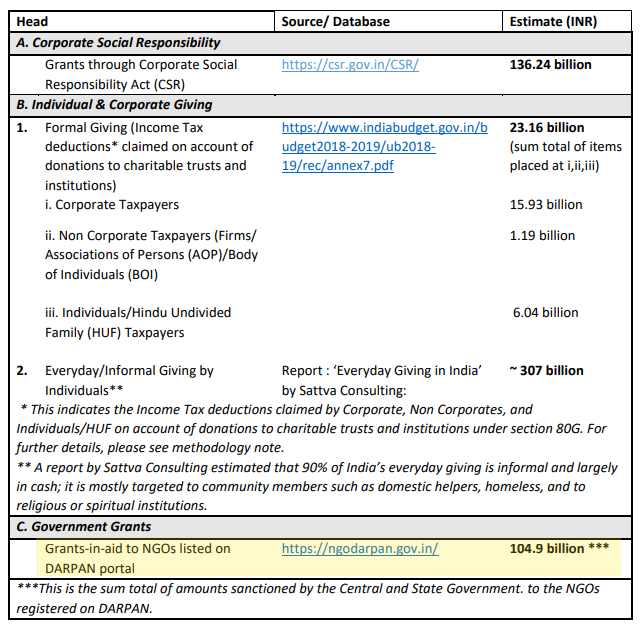

Government Grants to NGOs

The Indian government — through central ministries, state departments, CAPART, DRDA, ICDS, and dozens of scheme-specific channels — is the single largest funder of NGOs. In FY 2017–18, 58,624 NGOs registered on the DARPAN portal alone reported ₹10,490 crore in government grants.

Remember, this captures only a fraction of the true flow since many state-level grants and scheme-specific disbursements are not reported on DARPAN. Government funding to the voluntary sector has been growing since the Seventh Five Year Plan, when it was about ₹150 crore, to an estimated ₹1,000 crore+ by the late 1990s. A conservative annual estimate for the 2020s is ₹10,000–15,000 crore per year reaching NGOs directly.

Foreign Contributions (FCRA-regulated)

Under the Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act, foreign inflows into Indian NGOs have been tracked since 1976. In recent years:

- FY 2009–10: 21,508 associations received ₹10,338 crore (Source FCRA Annual Report)

- FY 2011–12: 22,702 associations received ₹11,546 crore (Source: FCRA Annual Report 2011-12)

- FY 2017–18: 23,592 NGOs received ₹16,821 crore

A working estimate for the recent decade is ₹10,000–17,000 crore per year, with ~₹15,000 crore as a reasonable central figure.

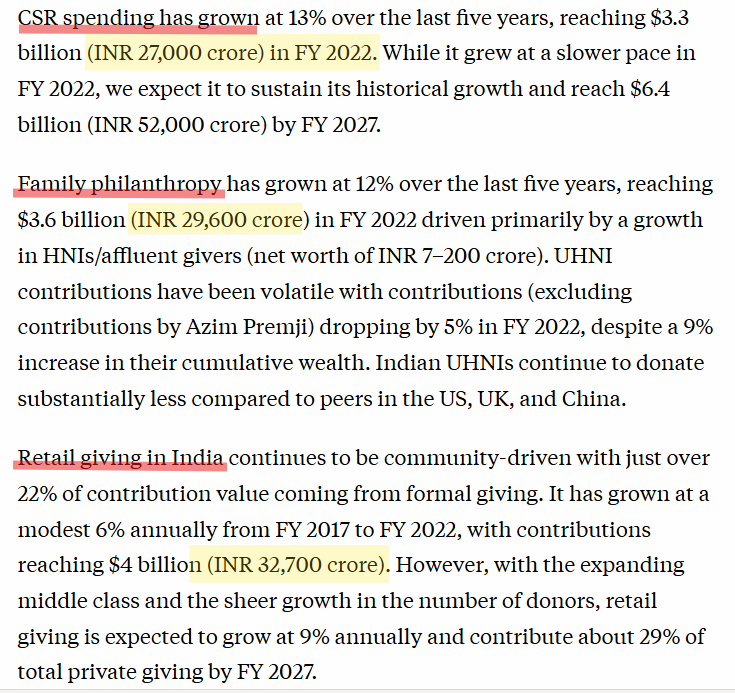

Domestic Private Philanthropy and CSR

This is now the fastest-growing stream, especially after the Companies Act 2013 mandated a 2% CSR spend for qualifying companies:

- FY 2022: Total private philanthropy ≈ ₹1,05,000 crore (CSR ≈ ₹27,000 crore; retail ≈ ₹33,000 crore; HNI/UHNI ≈ ₹29,000 crore)

- FY 2023: ≈ ₹1,20,000 crore

- FY 2024: ≈ ₹1,31,000 crore

Not all of this reaches NGOs — some goes to government funds, in-house corporate foundations, and direct spending — but a significant fraction is NGO-channeled.

India's total social sector spending (public + private) now stands at approximately ₹23 lakh crore (8.3% of GDP), though it still falls short of NITI Aayog's estimated 13% target for meeting SDGs by 2030.

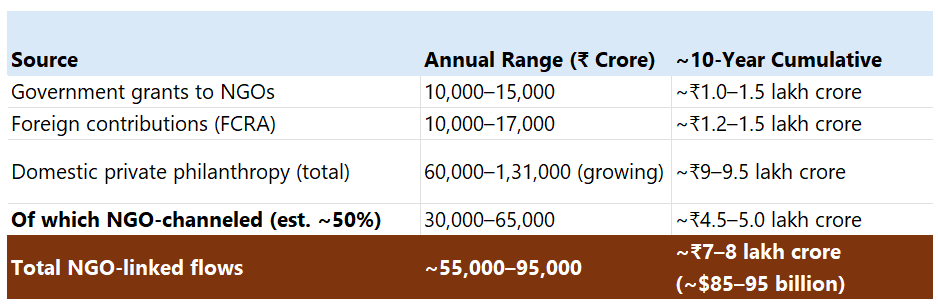

So, here's a conservative 10-Year Cumulative Estimate for the time period from FY 2015–2025.

We should remember that this is a lower-bound estimate. The true figure is likely higher.

What Have NGOs Actually Changed at National Scale?

During my college time, an economics professor in Delhi University said something very profund in a lecture:

I would venture out to say something similar.

If the amount of money given to the Indian NGOs for education had really been used for education (and not propaganda and 'busy work'), then the entire Indian population would have gotten a PhD by now!

What is in it for me? - isn't that what every Indian citizen should be asking?

This is the central question, and the honest answer is uncomfortable: despite lakh crore of funding, there is no rigorous, auditable evidence that India's mainstream NGO sector has shifted any major national index — GDP, literacy, pollution, green cover, river health — by a measurable, attributable amount.

In fact, the evidence may point to something else.

The IB Report's Damning Assessment

In 2014, the Intelligence Bureau submitted a classified report to the PMO alleging that foreign-funded NGOs were costing India 2–3% of GDP growth per annum by organizing agitations against nuclear power plants, coal-fired power plants, uranium mines, genetically modified crops, mega industrial projects, and hydroelectric projects.

As a first step to fast-tracking development high on Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s agenda, the Intelligence Bureau (IB) has submitted a classified document identifying several foreign-funded non-governmental organisations (NGOs) that are “negatively impacting economic development”. “A significant number of Indian NGOs (funded by some donors based in the US, the UK, Germany, The Netherlands and Scandinavian countries) have been noticed to be using people centric issues to create an environment which lends itself to stalling development projects,” says the IB report marked to the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO). “The negative impact on GDP growth is assessed to be 2-3 per cent per annum,” says the June 3 report, identifying seven sectors/ projects that got stalled because of NGO-created agitations against nuclear power plants, uranium mines, coal-fired power plants, farm biotechnology, mega industrial projects, hydroelectric plants and extractive industries. (Source: "Foreign-aided NGOs are actively stalling development, IB tells PMO in a report" / Indian Express)

The report named organizations including Greenpeace, Amnesty International, ActionAid, and Cordaid, and alleged they were "serving as tools for the strategic foreign policy interests of Western Governments".

Foreign Foundations as Political Instruments

The record on specific foreign foundations raises legitimate questions:

Ford Foundation funded Teesta Setalvad's Sabrang Trust (USD 290,000 between 2004–06), which was actively involved in creating fake stories on Gujarat riots in 2002.

Leaked Wikileaks emails showed Ford Foundation's president personally strategizing to prevent the Modi government from sending the foundation "packing" from India, deploying diplomatic contacts and Clinton-campaign connections.

Also, there is documented evidence of Ford Foundation and many other "philanthropic" organizations being an extension of the CIA. Here is an excerpt about the book by Frances Stonor Saunders titled Who Paid the Piper: The CIA and the Cultural Cold War

This book provides a detailed account of the ways in which the CIA penetrated and influenced a vast array of cultural organizations, through its front groups and via friendly philanthropic organizations like the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations. (Source: The CIA and the Cultural Cold War Revisited / Monthly Review)

Open Society Foundations (Soros-funded) were found to be routing money through intermediaries like CHRI-UK to circumvent FCRA restrictions after the Indian government placed them on a "prior permission" list. Between 2015 and 2022, the National Foundation for India received ₹58.1 crore in foreign donations, including from OSF, Ford Foundation, and Omidyar Network, and used the funds to train journalists and run media collectives aligned with donor ideology.

We have discussed Soros and the role his organizations play in subversive activities in detail.

Greenpeace India had its FCRA registration cancelled for being assessed as "working against the country's economic progress," particularly for campaigns against coal and nuclear projects. The government also froze its domestic accounts, going beyond FCRA powers.

These are not isolated incidents. They represent a pattern where foreign-funded NGOs operate as advocacy and agenda-setting vehicles for Western foreign policy interests, using Indian civil society as a front.

The Core Indictment

The contrast is stark and damning.

On one side: ₹7–8 lakh crore (~$85–95 billion) flowing to India's NGO sector over the past decade from government, foreign, and private sources — with no measurable national-scale outcome in education, health, environment, or poverty reduction that can be cleanly attributed to the NGO sector. On the other side: a handful of Hindu spiritual organizations, operating primarily on domestic donations and volunteer labor, that have:

- Brought drinking water to 3.19 million people in drought-ravaged districts

- Planted 122 million trees and shifted 238,000 farmers to sustainable agroforestry

- Fed 2.35 million children every single school day

- Built 45,000+ houses for the homeless

- Delivered ₹816 crore in free medical care

- Shaped national river policy adopted by 6 states and referenced by NITI Aayog

The difference is not just in scale — it is in accountability, tangibility, and alignment with national interest.

Dharmic organizations build infrastructure handed over to the government, plant trees that stay in the ground, feed children who show up at school, and construct houses where people live.

The foreign-funded NGO sector, by contrast, has been documented to stall development projects worth 2–3% of GDP, act as conduits for Western foreign policy agendas, and engage in political advocacy dressed up as philanthropy.

The question for India's policymakers, media, and citizens is not whether NGOs have a role — it is whether the current funding architecture, which pours lakh crore into a sector with no national-scale accountability, serves India's interests or someone else's.

Comments ()