The Dhurandhar Meltdown and the Reality

Dhurandhar doesn’t invent truth. It reveals it. The outrage proves the point: when clarity breaks silence, denial cries prejudice. Culture has finally spoken, shifting the Overton window and forcing a reckoning long obscured.

When cruelty becomes nourishment and hypocrisy becomes guidance, safeguarding truth becomes an act of survival - for the future itself.

The Drum at the Edge of the Village

At the edge of a quiet village stood an old drum.

No one remembered who placed it there.

For years, it gathered dust.

The villagers were proud of their silence.

“We are peaceful,” they said.

“We do not beat drums.”

But beyond the hills lived raiders who understood sound.

They struck only at night.

They did not announce themselves with armies,

only with screams, fire, and whispers that lingered after dawn.

The villagers buried their dead quietly.

They told their children, “Do not speak of this. Noise invites trouble.”

And so the drum remained untouched.

One winter, a young man named Dharmaketu walked to the drum and struck it once.

The sound rolled across the valley.

The elders rushed out in anger.

“You are dangerous,” they said.

“You are prejudiced. You are provoking fear.”

Some accused him of loving the drum more than the village.

Others said he was exaggerating the danger.

A few insisted the drum itself caused the violence.

Dharmaketu bowed and said nothing.

That night, the raiders came again.

But this time, the village heard them early.

Torches were lit. Doors were barred.

Children were moved to safety.

The raiders fled, confused—not by force, but by readiness.

The next morning, critics gathered around the drum.

One said, “The drum is too loud.”

Another said, “The drum divides us.”

A third said, “We should study the drum for ten more years before touching it again.”

An old monk, who had watched silently, spoke at last:

“The drum did not create the raiders.

The drum did not invent fear.

The drum only revealed what was already walking toward you.”

The monk continued:

“When truth is whispered, it is called wisdom.

When truth is spoken aloud, it is called prejudice.

When truth is struck like a drum, it is called dangerous—

until the night proves it necessary.”

The villagers looked again at the drum.

They noticed something they had missed before.

It was cracked. Old. Imperfect.

But it still worked.

The monk smiled.

“Culture,” he said, “speaks last.

Long after scholars debate and politicians deny,

culture beats the drum and records the verdict.

Not to inflame—but to remember.”

From that day on, the village did not beat the drum in anger.

Nor did they pretend it was not there.

They beat it only when needed. And the night, slowly, lost its power over them.

The drum remained at the edge of the village. Not as a weapon. Not as an idol.

But as a reminder: Silence does not make danger disappear. Clarity does.

SUPPORT DRISHTIKONE

In an increasingly complex and shifting world, thoughtful analysis is rare and essential. At Drishtikone, we dedicate hundreds of dollars and hours each month to producing deep, independent insights on geopolitics, culture, and global trends. Our work is rigorous, fearless, and free from advertising and external influence, sustained solely by the support of readers like you. For over two decades, Drishtikone has remained a one-person labor of commitment: no staff, no corporate funding — just a deep belief in the importance of perspective, truth, and analysis. If our work helps you better understand the forces shaping our world, we invite you to support it with your contribution by subscribing to the paid version or a one-time gift. Your support directly fuels independent thinking. To contribute, choose the USD equivalent amount you are comfortable with in your own currency. You can head to the Contribute page and use Stripe or PayPal to make a contribution.

Dhurandhar Strikes

“Dhurandhar” stitches together strands from several real operations and episodes – IC 814 (Kandahar hijack), Pakistan‑printed fake Indian currency, Karachi’s Lyari underworld, and networks behind 26/11 – but does so in a compressed, dramatized universe that exaggerates linkage and timing for narrative effect.

What are the main themes of the movie?

Pakistani deep state and proxy war: The film foregrounds the ISI’s use of jihadi groups, Karachi gangs and counterfeit currency as tools in a long war “below the threshold” against India, echoing documented use of Nepal, Karachi and Gulf routes for terrorists, explosives and Fake Indian Currency Notes (FICN).

Fake currency as strategic weapon: A core thread is a state‑protected FICN racket, with senior politicians and security officials compromised, reflecting public allegations that Pakistan‑printed high‑quality notes were used both to fund terrorism and to destabilise the Indian economy

Karachi underworld and urban warfare: The Lyari sector of Karachi, ganglord fiefdoms, and a “dirty war” between police, gangs and intelligence services mirror real operations against Lyari gangs and the role of crime‑terror nexuses in Karachi.

Covert Indian penetration of Pakistani networks: Ranveer Singh’s protagonist operates as an Indian asset embedded in Pakistani criminal‑terror structures, clearly referencing Indian deep‑cover infiltration of Pakistan‑backed groups even though the exact composite operation in the film is fictionalised.

Series of terror events (IC 814 to 26/11): The narrative ties fake currency, Kandahar, Parliament attack and 26/11 into one continuous, centrally choreographed conspiracy, which aligns with some political‑strategic readings but condenses many complex strands into a single plotline.

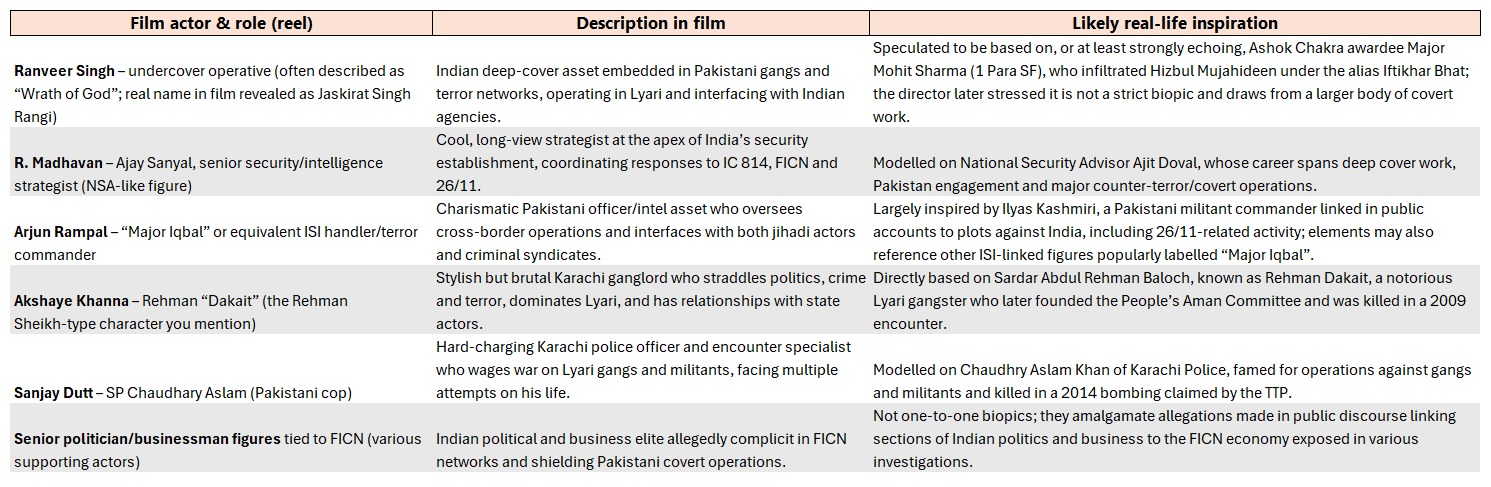

The characters and the real life inspiration of those roles can be broken down as follows:

We will go through all the themes in our discussion below.

But first the critics

The Meltdown from Indian Islamists and Left-Liberal Gangs

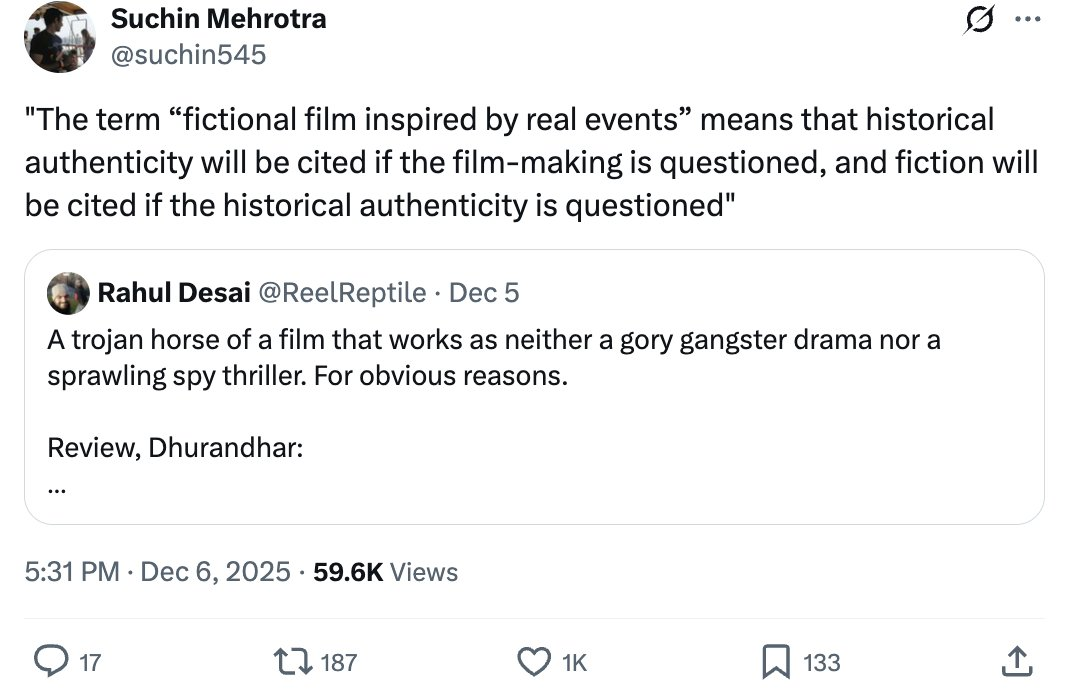

The reaction to Dhurandhar reveals something deeper than a routine ideological disagreement—it exposes panic. For decades, control over Indian cinema’s “acceptable” narratives rested with a narrow left-liberal ecosystem that dictated who could tell stories, how nationalism could be portrayed, and which conflicts were morally legible. That ecosystem is now losing its monopoly.

The anxiety is not about craft or ethics. The film’s technical competence, genre discipline, and narrative confidence make it harder to dismiss as crude propaganda. What truly unsettles the old gatekeepers is that cinema they do not ideologically own is now fluent in cinematic language itself. The familiar trick -branding dissenting narratives as unsophisticated or dangerous - no longer works when the storytelling is tight, immersive, and popular. The so-called film critics have been at it showcasing their anti-Hindu and Islamist apologist mindset.

Also check out Anupama Chopra.

These movie critics were not satisfied with the peddling of their fake and bigoted narratives.

So they used a body that they have created (Anupama Chopra is the Chairperson of FCG) to denounced everyone who was criticizing these critics. The statement was positioned as a defense of “editorial autonomy” and “independent criticism”. (Source: Private body ‘Film Critics Guild’, headed by critics Anupama Chopra and Sucharita Tyagi, condemns criticism of their reviews of Dhurandhar / Opindia)

Irony, anyone?

That is the level of hatred for competing voices in the field of movies and journalism in India!

For years, Pakistan-centric and “strategic ambiguity” narratives dominated Hindi cinema, soft-pedaled through moral equivalence, selective empathy, and coded aesthetics. That dominance shaped public perception quietly but powerfully. Dhurandhar breaks that spell—not by shouting slogans, but by normalizing an alternative lens and trusting audiences to engage without elite mediation.

This is why the response feels hysterical rather than critical. When narrative control slips, outrage replaces analysis. The panic stems from a realization: cinema is no longer a credentialed space. It is becoming a contested one—and the audience has moved on.

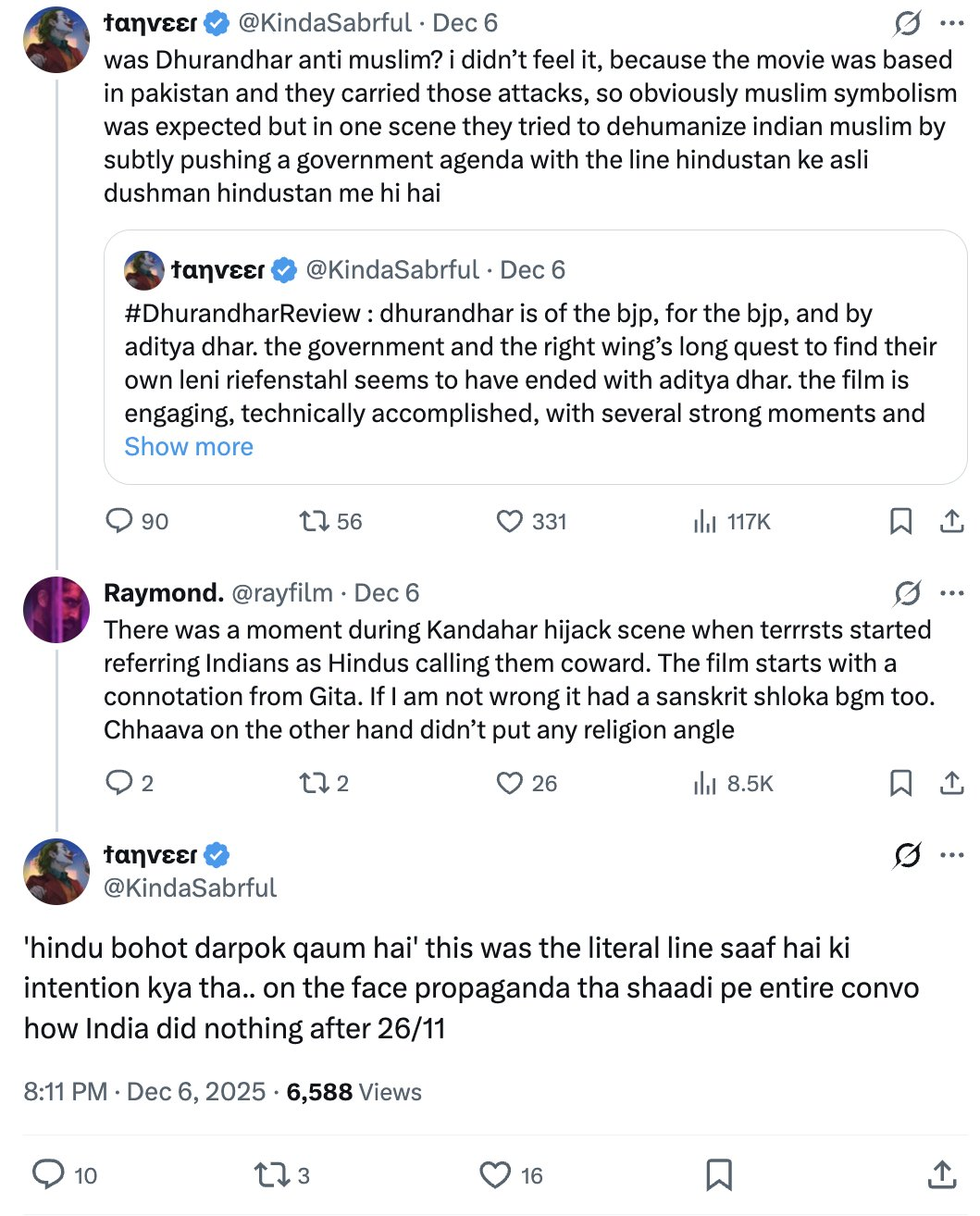

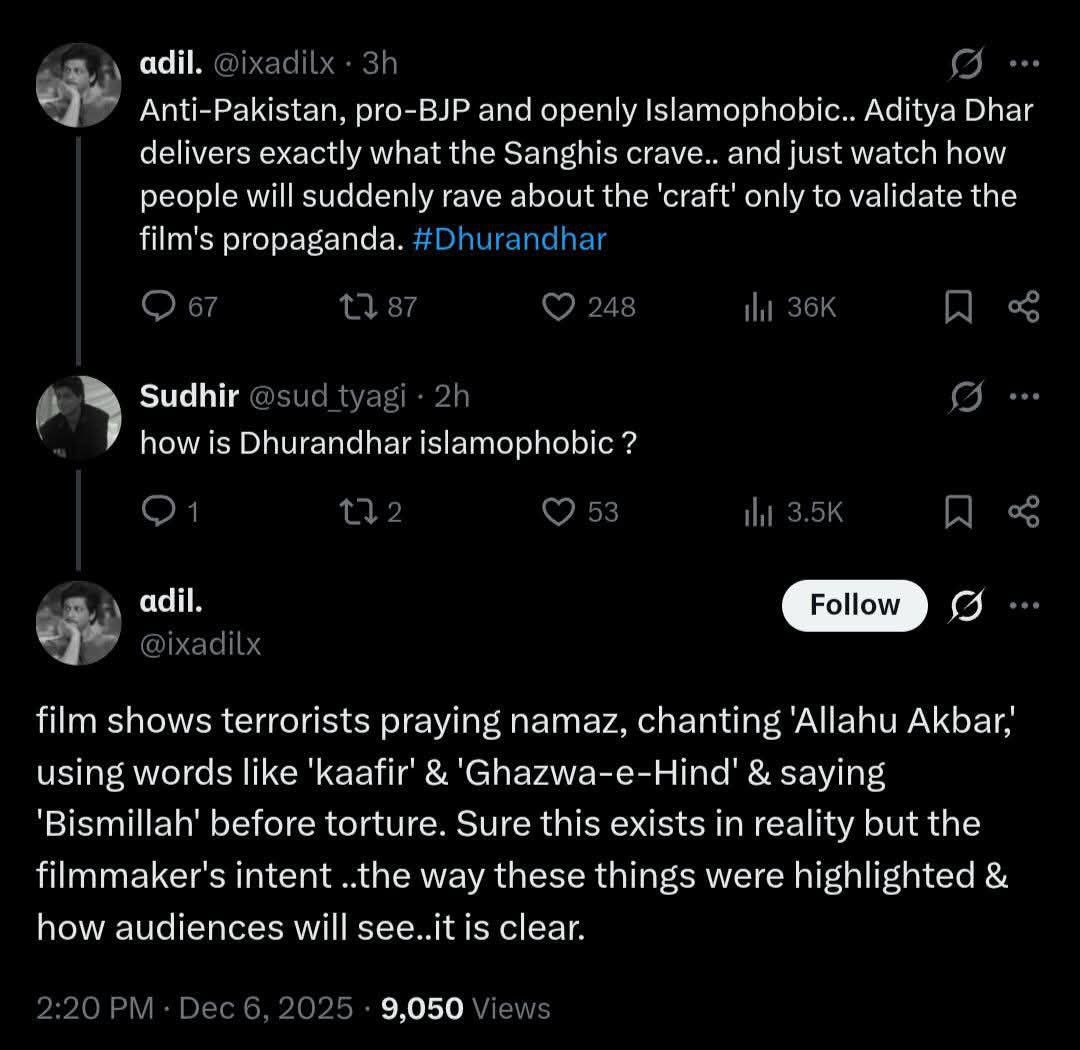

Arfa Khanum’s rant against Dhurandhar inadvertently exposes the core dishonesty of the outrage. Her claim—that the film maligns Muslims by depicting their symbols, speech, treatment of women, and behavioral codes—collapses under even minimal scrutiny. Symbols, dress, language, and conduct are not imposed by cinema; they are choices made by actors within a social and ideological ecosystem. A film that depicts those choices realistically is not “targeting” a community. It is documenting a pattern.

But for the Jihadi apologists and sympathizers like Arfa and the person below, reality is the issue.

The real discomfort is not about misrepresentation, but about representation itself.

Notably, the outrage is not directed at the gore, torture, or terror inflicted in reality.

There is no visible horror at the beheadings, bombings, trafficking of women, or the ideological machinery that sanctifies violence from mosques and intelligence handlers alike. The horror arises only when these realities are shown on screen—unfiltered and unashamed.

Movies were the backbone on which Congress leaders like Nehru and Indira Gandhi had constructed their political legitimacy.

For much of post-Independence India, Hindi cinema operated as an informal ideological extension of the Congress state. Films such as Naya Daur (1957) and Jagriti (1954) did not merely reflect social realities; they actively promoted Nehruvian socialism—state paternalism, suspicion of private enterprise, and moralized collectivism.

Large sections of Raj Kapoor’s filmography reinforced this worldview, blending sentimentality with socialist romanticism at a time when dissenting ideological spaces were institutionally suppressed.

This narrative capture persisted well into the modern era. Films like Haider, Mission Kashmir, and Fanaa presented Kashmir through a selective moral lens -foregrounding state excesses while marginalizing or relativizing Islamist violence, the ethnic cleansing of Kashmiri Pandits (1989–90), and the role of Pakistan-backed terror groups.

Victimhood was aestheticized; perpetrators were humanized.

Even more striking was the sustained romanticization of Pakistan’s ISI in mainstream spy franchises—Ek Tha Tiger, Pathaan, Tiger Zinda Hai, Tiger 3, The Hero: Love Story of a Spy.

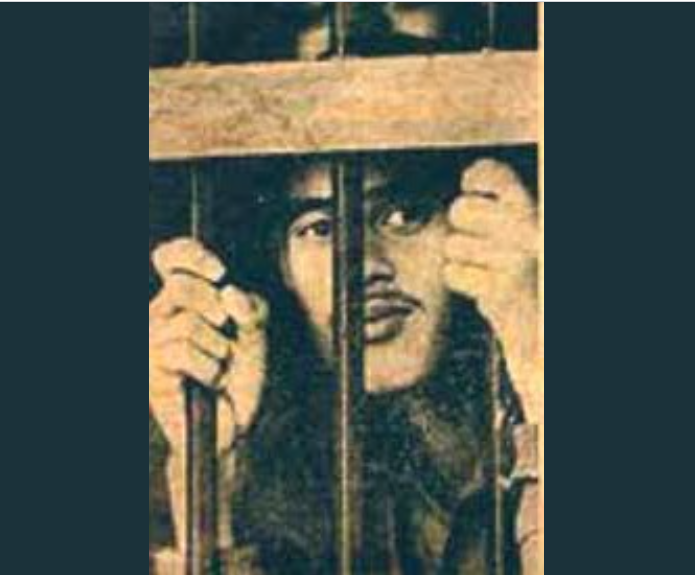

These portrayals stood in grotesque contrast to documented realities: the mistreatment of Indian POWs after the 1971 war and the brutal torture and murder of Saurabh Kalia during Kargil in 1999—events acknowledged in Indian parliamentary records and military inquiries.

Bhutto had shared the fate of the roughly 54 Indian Prisoners of war from 1971, which was in stark contrast to the treatment that 93,000 Pakistan PoWs received in India.

When her father Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, an ousted prime minister himself, was on the death row, prison officials had tried to make his stay as miserable as possible. To disturb his sleep, they would torture the PoWs held in the cell next to his, and make the soldiers scream in the dead of night. The events of those days, including the one in which the Indian PoWs figured, was later to be made famous by a former BBC correspondent Victoria Schofield in her book, Bhutto: Trial and Execution. In the relevant passage of the book, she wrote: "In addition to these conditions at Kot Lakhpat (jail), for three months Bhutto (Zulfikar Ali Bhutto) was subjected to a peculiar kind of harassment, which he thought was especially for his benefit. "His cell, separated from a barrack area by a 10-foot-high wall, did not prevent him from hearing horrific shrieks and screams at night from the other side of the wall. One of Mr Bhutto's lawyers made enquiries among the jail staff and ascertained that they were in fact Indian prisoners-of-war who had been rendered delinquent and mental during the course of the 1971 war. "Bhutto, discovering the precise temperament of the inmates, wrote to the jail superintendent with a copy of the letter addressed to his lawyer (which was released to the press), requesting that they be moved - finally they were. Obviously the authorities would not accept that Mr Bhutto's sleep was being disturbed on purpose, but Bhutto did not forget the sleepless nights he spent and referred often to the lunatics in other letters of complaint. 'Fifty odd lunatics were lodged in the ward next to mine. Their screams and shrieks in the dead of night are something I will not forget,' he wrote." (Source: Benazir confirms 41 prisoners of 1971 war/ Times of India)

Look at this picture and the eyes that were still waiting. He was Major AK Ghosh of the 15 Rajput regiment.

It is instructive to note that this Congress/Secular/Leftist ecosystem was enforced through coercion.

During Congress rule, films critical of the regime were routinely stalled or banned under the Cinematograph Act.

Artists paid a personal price: Majrooh Sultanpuri was imprisoned (1949–51) for criticizing Nehru, and Balraj Sahni faced incarceration and blacklisting for political dissent. Listen to this little piece that I had rendered a few years back.

Here are some more details:

So, do you see the real picture?

Let us go into the themes of the movie.

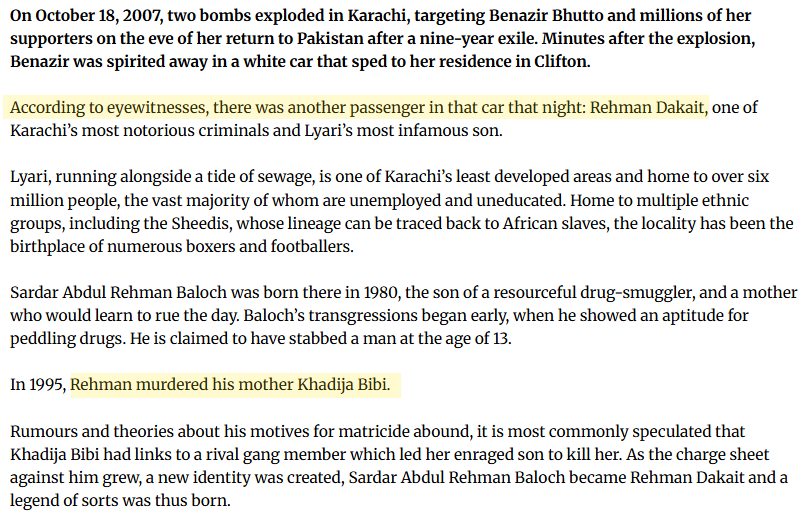

Lyari Gangs: Who was Rehman Dakait?

Rehman Dakait, born Sardar Abdul Rehman Baloch in Lyari, rose from street crime to become Karachi’s most feared gang leader. His ascent was enabled by chronic state absence, unemployment, and long-standing political patronage in Lyari, a city that was historically a stronghold of the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP).

Lyari is one of Karachi’s oldest inhabited areas and is often described as the “Mother of Karachi”, a title rooted in history rather than sentiment.

Long before Karachi emerged as a major port city under British rule, Lyari was settled by Sindhi fishing communities and Baloch nomadic tribes, whose livelihoods were tied to the Lyari River and the Arabian Sea. These early settlements predate modern Karachi’s urban expansion and formed the city’s original human and economic base.

During the Talpur and later British periods, Lyari functioned as a working-class hub, supplying labor, dock workers, craftsmen, and soldiers to the growing port city. Its dense lanes, communal housing, and strong kinship networks reflected a self-contained social order shaped by poverty, resilience, and deep ethnic solidarity—particularly among Baloch clans who trace their presence back centuries.

Lyari also developed a distinct cultural and political identity. It became a cradle of trade unionism, leftist politics, and resistance movements, while simultaneously nurturing a powerful sporting culture—especially football and boxing—that earned national recognition. Only in the late 20th century did Lyari become synonymous with gang warfare, narcotics, and criminal patronage, largely due to state neglect, political manipulation, and the collapse of lawful economic opportunities.

It is said that when an attempt was made on Benazir Bhutto's life in October 2007, she had Rehman Dakait also in her car. To fully understand the monstrosity of Rehman, one needs to realize that he did not shy away from matricide when it suited him.

After taking over Haji Laloo’s gang, Dakait built a criminal empire spanning extortion, kidnappings, narcotics, and arms trafficking, paralyzing Lyari through prolonged gang wars. Despite repeated arrests, he escaped custody, reinforcing claims of police protection.

His proximity to power was evident in photographs with senior politicians and reports placing him near Benazir Bhutto during her 2007 Karachi return. In 2008–09, Dakait attempted political legitimation through the People’s Aman Committee (PAC), projecting a “Robin Hood” image—funding schools and madrassas while brokering gang truces—often amid PPP symbolism.

Beyond local crime, multiple journalistic and security accounts have alleged Dakait’s connections to militant ecosystems. These include arms supply routes to Baloch insurgents and transactional links with Karachi-based jihadist facilitators who historically overlapped with criminal networks patronized by Pakistan’s security apparatus. Analysts have noted how Lyari gangs functioned as logistics, protection, and fundraising nodes that intersected with outfits tolerated or leveraged by Inter-Services Intelligence for deniable operations—though official denials persist and many claims remain unprosecuted.

Dakait was killed in a 2009 police “encounter,” widely suspected to be extrajudicial. His death exposed the toxic nexus of crime, politics, and militancy—leaving Lyari calmer, but structurally unchanged.

Karachi Underworld, ISI and Dawood Ibrahim

Transnational syndicates don’t thrive on “muscle” alone; they thrive on infrastructure—the kind created by transit corridors, ports, and embedded smuggling ecosystems.

Once a route becomes normalized for high-volume contraband (consumer goods, gold, narcotics, weapons), it also becomes efficient for the other necessities of a clandestine enterprise: hawala/hundi value transfer, forged documentation, safehouses, container manipulation, and corrupt facilitation at chokepoints. Analyses of the Afghan–Pakistan transit and trucking/smuggling milieu highlight how logistics networks can mature into durable criminal supply chains, especially when enforcement is selective or politically constrained.

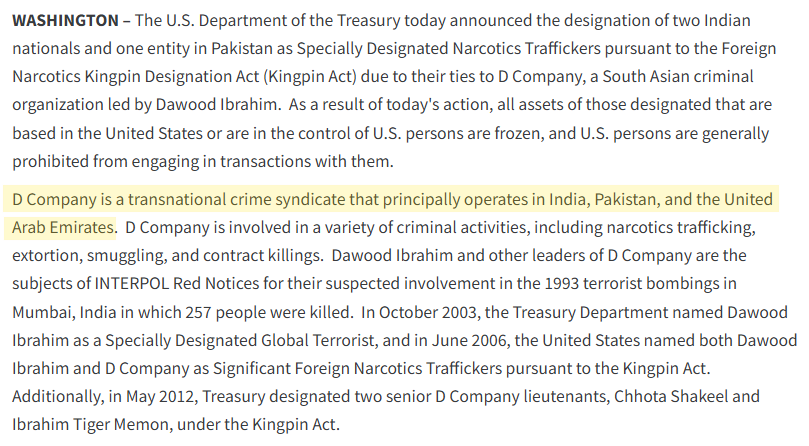

This is why the India–Pakistan–UAE triangle is so strategic for syndicates like D-Company. The U.S. Treasury describes D-Company as a transnational crime syndicate that “principally operates in India, Pakistan, and the United Arab Emirates,” engaged in narcotics trafficking, extortion, smuggling, and contract killings.

That characterization maps to a classic functional geography:

- Mumbai (markets & targets): revenue generation and coercion (extortion, enforcement, contracts) in a dense commercial ecosystem.

- Karachi (sanctuary & routing): proximity to major port/airport nodes and smuggling corridors, plus the strategic value of protection from pursuit—an essential factor for leadership continuity.

- Dubai/UAE nodes (finance & movement): historically significant as a regional hub for trade flows and informal value transfer, enabling rapid movement of money and personnel in ways formal banking scrutiny can struggle to match.

International designations reinforce the “hybrid” nature of such networks: Dawood Ibrahim is listed by the UN 1267 sanctions regime (narrative summary available on the UN site), and the U.S. has separately sanctioned him under terrorism and narcotics authorities—signaling the perceived crime–terror overlap in his ecosystem.

Bottom line:

- ports and transit routes create the plumbing;

- syndicates exploit that plumbing to fuse trade-based smuggling + informal finance + violence, spanning jurisdictions where each node offers a different comparative advantage.

Now let us understand the Crime-Terror Nexus that was set up by Pakistan to control and direct crime in India and use it as the launching pad for its nefarious terror activities.

The Karachi crime-terror nexus involves powerful criminal organizations (like Lyari gangs) and militant/terrorist groups (like AQIS, TTP, Baloch militants) collaborating and clashing for economic and political control, utilizing Karachi's port and vast underworld for drug trafficking, arms smuggling, extortion, and financing, creating a complex, violent environment where ideologies merge with criminal profit motives, impacting Pakistan's stability.

Key elements include drug trade financing terrorism (e.g., Taliban/AQIS), criminal groups providing logistical support (e.g., D-Company for ISI/militants), and terrorist tactics adopted by criminals, all feeding instability. Key Actors & Dynamics

- Criminal Syndicates: Groups like Dawood Ibrahim's D-Company operate globally but are rooted in Karachi and Mumbai, often partnering with state/non-state actors for arms and finance. Lyari gangs are major players in local crime and violence.

- Terrorist/Militant Groups: Al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS), Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), and Baloch militants use Karachi's illicit networks for funding, logistics, and recruitment.

- State/Intelligence Agencies: Pakistan's intelligence (ISI) has historically used criminal networks, like D-Company, for operations, notably in Kashmir, blurring lines between state-sponsored action and organized crime.

Source: D-company: a study of the crime-terror nexus in South Asia by Ryan Clarke / January 2010, International Journal of Business and Globalisation

So did the Indian intelligence infiltrate the Lyari gangs in Karachi as shared in the movie Dhurandhar via the character played by Ranveer Singh? The answer is yes!

Here is Omar Shahid Hamid DIG Sindh Police and protégé of Chaudhary Aslam openly admitting that Indian intelligence infiltrated Karachi’s gangs and key institutions across the board.

A top-ranking Pakistani police officer saying this on record isn’t just a “statement.”

We have to remember that communal violence and riots in India have been orchestrated by the Pakistani intelligence and their criminal non-state actors like Dawood.

The Culture of Inhuman Torture

The trailer of the movie shows a brutal scene from the beginning. Apparently, it is the character of Ilyas Kashmiri that Arjun Rampal plays as Major Iqbal.

Here is the trailer:

We will go through the evidence of inhuman torture that is the bedrock of Pakistani culture and investigate what has caused it.

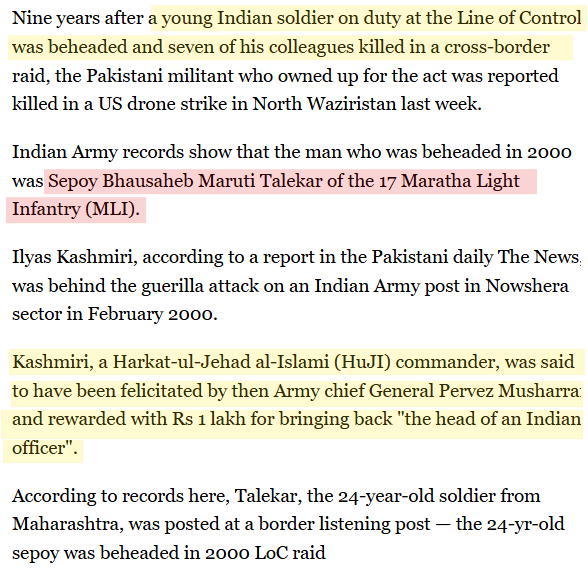

Ilyas Kashmiri was responsible for the beheading of the Indian jawan Sepoy Maruti Talekar.

But Sepoy Talekar was not alone who faced this fate.

Captain Saurabh Kalia and his patrol were subjected to prolonged, systematic torture while in Pakistani custody during Kargil, and there is a separate, well‑documented beheading case in which militants led by Ilyas Kashmiri decapitated an Indian soldier and a captured militant later stated that his severed head was used as a football.

Torture of Captain Saurabh Kalia

Captain Saurabh Kalia of 4 Jat and five jawans (Naik Arjun Ram, Sepoys Bhanwar Lal Bagaria, Bhika Ram, Moola Ram and Naresh Singh) were captured on 15 May 1999 after a firefight in the Kargil sector and held for about 22 days by Pakistani forces before their bodies were returned on 9 June 1999. Post‑mortem examinations in India recorded extensive pre‑mortem mutilation: multiple cigarette burns, ear‑drums pierced with hot rods, numerous broken teeth and bones, skull fractures, eyes gouged out, lips and nose cut, limbs and genitals amputated, and finally gunshot wounds to the head.

In gross violation of the Geneva Convention the Pakistani Army subjected Captain Kalia and his soldiers to horrendous torture during which the bravehearts’ ear drums were pierced with hot iron rods, eyes punctured and genitals cut off. The autopsy of the bodies also revealed that they were burned with cigarettes butts. Their limbs were also chopped off, teeth broken and skull fractured during the torture. Even their nose and lips were cut off. (Source: "Pakistan Army punctured eyes, cut off genitals of Captain Saurabh Kalia and his soldiers but Centre refuses to act" / News18)

Indian authorities and Kalia’s family have consistently described this as a flagrant violation of the Geneva Conventions, and have pushed—without success so far—for international recognition of the torture and for Pakistan to be held accountable. Years later, a video surfaced of a Pakistani soldier narrating the encounter in which Kalia’s patrol was captured, reinforcing that they were taken alive and contradicting earlier Pakistani denials that such an incident occurred.

How does this culture of extreme demonic proportions become ingrained in the so-called Pakistani Army (it is a disgrace to equate such a demonic force with any uniformed soldier)?

The answer lies in the indoctrination they receive.

Under General Zia-ul-Haq, Pakistan initiated a deliberate Islamisation of the Army, moving away from the British–Indian secular traditions that had shaped its character since independence.

For the first time, Islam was formally integrated into the institution’s structure and values. Islamic teachings were incorporated into the curricula of the Pakistan Military Academy and the Command and Staff College, emphasizing religious guidance alongside military training.

A Directorate of Religious Instruction was created to educate and advise officers on Islamic principles, aligning their conduct with religious ideals.

Moreover, Islamic studies became a mandatory component in promotion examinations, embedding faith-based understanding into professional advancement and redefining the ideological orientation of Pakistan’s military leadership.

Pakistan’s military leadership under Zia-ul-Haq made religious ideology central to officer training and evaluation.

This integration of piety with professionalism transformed the promotion system, making religious devotion a key criterion.

As a result, many capable but secular officers were sidelined for failing to embody the model of a “good Muslim.”

The policy ultimately elevated ideologically conservative officers to senior command and infused radical Islamist thinking throughout military training institutions.

Read this extract from the book "Frontline Pakistan" by Zahid Hussain (a leading Pakistani journalist).

Brigadier S. K. Malik’s The Quranic Concept of War is not merely a theological text; it is a doctrinal blueprint that profoundly shaped Pakistan’s strategic culture.

Malik argues that war for a Muslim state transcends material or territorial objectives and constitutes a spiritual, ideological, and psychological struggle. In his framework, jihad functions as “total strategy”—policy-in-execution across all domains: political, social, economic, psychological, and military.

What are central doctrinal pillars of this book.

Victory Redefined: Drawing heavily on Malik’s interpretation of the Battle of Uhud (625 CE), he rejects materialist definitions of defeat. Despite battlefield losses and casualties, Uhud is framed as a victory of faith because it reinforced commitment to jihad.

In this formulation, Victory = persistence of will, not battlefield success.

Perpetual Conflict: Malik treats war not as an exception but as a permanent condition. Peace is merely tactical; struggle is eternal. This primes a military for continuous confrontation, even after repeated setbacks.

Kinetics Are Secondary: Material inferiority—economic weakness, loss of territory, military imbalance—is irrelevant if ideological resolve survives. Defeat occurs only when the will to fight collapses.

Terror as the Objective of War: Most controversially, Malik elevates terror from a tactic to the central object of war. Citing Quranic injunctions to instill fear in the enemy, he argues:

Victory is achieved not when armies are destroyed, but when the enemy’s soul is paralyzed.

Terror, in Malik’s view, is the decision imposed upon the enemy, not collateral damage.

It is of strategic importance to remember that: you don’t get to “opt out” of an adversary’s intent.

Even if a society prefers to debate development, trade, or politics, a violence-based project can still target it - and can do so in ways designed not only to kill, but to break nerve, impose humiliation, and reshape public psychology.

That said, it’s crucial to name the actor precisely: this is not about “Pakistanis” as a people. It’s about a state–militant ecosystem - elements of Pakistan’s military-intelligence apparatus, allied jihadist outfits, and criminal facilitators - using calibrated violence as strategy.

The doctrinal backdrop: fear as an objective, not a byproduct

The passage we shared earlier (about Zia-era Islamization of the army and required reading of The Quranic Concept of War) matters because it signals how a military can be trained to treat religion-infused psychological warfare as doctrine, not rhetoric. A widely cited Zia line—used in military studies of Pakistan’s strategic culture—frames “professionalism” in explicitly religious terms (“the color of Allah”), tying soldiering to an ideological mission.

Within that ideological frame, Malik’s argument (as summarized and analyzed in U.S. military professional literature) treats war as more than terrain and casualties: it is spiritual, moral, and psychological struggle, with the enemy’s mind as a key center of gravity.

The notes by SK Malik in his book say that “victory” becomes persistence of jihad, not battlefield outcomes, and fear becomes the lever.

This produces a specific motivation-set:

- Humiliation and terror are not accidental excesses; they can be interpreted as tools to force political behavior.

- Setbacks don’t equal defeat if the adversary’s society remains anxious, polarized, and distrustful.

- Perpetual conflict is sustainable if the goal is psychological pressure rather than conventional conquest.

The historical pattern: violence that performs a message

When you look back at major episodes—1947–48, 1971, and later proxy-war decades—the recurring logic is not only killing, but message-making through cruelty.

1947–48: irregular invasion logic: Open-source scholarship on Kashmir’s accession and the 1947 crisis describes how irregular fighters/tribal raiders led by Pakistan's military officers advanced amid widespread terror against civilians - violence that created panic, flight, and political shock. Rape camps where nuns from the local seminary were gang-raped repeatedly in Muzaffarabad is a well known example.

Whatever side one takes on the broader Kashmir dispute (and it is contested), the operational idea is recognizable: irregular brutality can “soften” territory psychologically before regular politics and diplomacy settle the map.

1971: mass violence as intimidation and punishment: On 1971, there is extensive academic literature on atrocities and mass sexual violence during the Bangladesh war.

Even Pakistan’s own Hamoodur Rahman Commission material (as published/leaked in parts) discusses severe excesses, killings, and sexual violence, and frames moral/professional breakdowns as central to the catastrophe.

The strategic takeaway isn’t “history as grievance”. It’s method: mass terror and sexual violence function as collective humiliation, aimed at breaking social cohesion and will.

Scholarly discussions of 1971 emphasize that such violence is often used to terrorize communities into submission by attacking “honor” through women’s bodies.

Post-1980s to 2000s: proxy jihad and spectacle attacks: The later evolution is the move from mass campaigns to high-salience spectacle attacks - operations engineered for maximum psychological effect, media dominance, and national trauma. The 2008 Mumbai attacks were clearly carried out by Pakistan-based Lashkar-e-Taiba, and Western analysis has repeatedly stressed the group’s ability to plan and operate from Pakistan despite international pressure.

That is the “terror as messaging” model: select iconic targets, maximize helplessness, stretch the event across time, and ensure the victim society experiences fear + humiliation + helplessness in real time.

Fake Currency Notes Scandal

There was a systemic compromise of India’s currency system during the UPA era that ultimately contributed to a situation that led to the 2016 demonetization.

There was a long-running and deeply consequential breach in India’s banknote printing and security ecosystem, one that combined bureaucratic impropriety, compromised procurement processes, and national-security vulnerabilities.

Investigations revealed that for years, highly sophisticated counterfeit Indian currency notes (virtually indistinguishable from genuine ones) circulated not only in border regions but were also discovered within formal banking channels, including reserve holdings. This raised alarming questions about how such notes entered the system undetected.

At the center of the controversy was the extension of currency-printing and paper-supply contracts to foreign firms despite red flags, blacklisting decisions, and security objections.

One such firm - De La Rue - had simultaneous access to the currency systems of both India and Pakistan, creating a structural vulnerability in note design, paper specification, and production secrecy.

The continuation of these contracts, even after internal warnings and adverse intelligence inputs, suggested institutional capture and gross negligence at senior levels of the finance bureaucracy.

Parallel intelligence assessments linked the counterfeit currency pipeline to Pakistan-based networks, with fake notes used not merely for economic disruption but as a tool of financial warfare - funding terror, destabilizing markets, and eroding public trust in the currency itself.

The scale and quality of the counterfeiting operation indicated state-level facilitation rather than isolated criminal activity.

These accumulated failures formed a backdrop to the 2016 demonetization decision, which abruptly withdrew high-denomination notes from circulation.

While demonetization was publicly framed as a move against black money and corruption, it also functioned as an emergency reset of the currency system—invalidating compromised notes, breaking counterfeit stockpiles, and forcing a redesign of banknote security architecture.

Subsequent investigations, including high-profile raids and inquiries, exposed how procedural violations, opaque decision-making, and disregard for national security considerations had allowed the breach to persist for years.

Please read a detailed discussion on the Currency scandal on India in this article.

IC-814 Hijacking: What Happened and Why It Still Matters

On December 24, 1999, Indian Airlines Flight IC-814, an Airbus A300 flying from Kathmandu to Delhi, was hijacked shortly after entering Indian airspace. On board were 176 passengers and crew, including families, children, and Indian officials. The hijackers - five Pakistani terrorists - were later confirmed to be members of Harkat-ul-Mujahideen, operating with external logistical support.

The aircraft was first forced to land in Amritsar, where Indian authorities lost a crucial window to immobilize the plane. Due to indecision and lack of preparedness, IC-814 was allowed to take off again. It then flew to Lahore, where Pakistani authorities denied it formal landing clearance but permitted refueling under cover of darkness. From there, the aircraft was flown to Dubai, where one passenger, Rupin Katyal, was brutally murdered by the hijackers to intensify pressure.

Relatives of IC 814 passengers started a very shrill protest and "gheraoed" (surrounded/besieged) officials, especially in the initial days and later with demands for so-called "justice/accountability", demanding answers from the government. They wanted to let the terrorists go for the lives of their relatives. There was no care for India's integrity and security. That siege did not allow the time for negotiation when Ajit Doval wanted it. Yes, the government messed up but the emotions of the relatives was also weaponized against India's security.

The final destination was Kandahar, then under the control of the Taliban. For seven days, the passengers were held hostage in Taliban territory, while negotiations took place under intense international and domestic pressure. The hijackers demanded the release of jailed terrorists in India, safe passage, and political concessions.

Zahid Hussain shares the collaboration between Taliban, ISI and the Jihadis and how the released jihadi terrorists found their way to Pakistan to further start new terror organizations targeted against India.

Ultimately, the Indian government agreed to release three high-value terrorists in exchange for the hostages:

- Masood Azhar, who would later found Jaish-e-Mohammed and orchestrate major attacks against India.

- Ahmed Omar Saeed Sheikh, later convicted for the kidnapping and murder of journalist Daniel Pearl.

- Mushtaq Ahmed Zargar, a senior militant commander.

The terrorists were flown to Kandahar and released under Taliban supervision. Shortly afterward, all hostages were freed.

The consequences were profound. The hijacking exposed severe weaknesses in India’s crisis response, aviation security, and decision-making chain. More critically, the release of Masood Azhar directly enabled the creation of Jaish-e-Mohammed, responsible for attacks such as the 2001 Indian Parliament assault, Pathankot (2016), and Pulwama (2019).

IC-814 remains a defining moment in India’s counter-terrorism history—a case study in how terrorist coercion, state sponsorship, and diplomatic paralysis combined to extract strategic concessions through the calculated use of civilian hostages.

Dhurandhar and the Movement of the Overton Window

What makes Dhurandhar a genuine game-changer is not simply its narrative or craft, but its timing.

It arrives at the moment when the gap between lived experience and officially permitted discourse has become too wide to sustain. In that sense, Dhurandhar does not invent a new reality; it acknowledges one that already exists - and by doing so, it shifts the Overton window.

Dhurandhar performs precisely that function. It takes themes that were long relegated to whispers such as betrayal, psychological warfare, moral asymmetry, humiliation as strategy, and places them unapologetically in the public, cultural space.

Once culture does this, the debate is no longer about whether these realities exist, but how society should respond to them.

This is where culture differs from politics or academia. Policy reacts. Scholarship analyzes.

Culture records verdicts.

It captures the emotional truth of an era after the intellectual battles have already been fought and exhausted. That is why cultural shifts often appear late - at the fag end of denial, when pretending no longer works.

By the time a society allows such stories to be told on screen, it has already internalized their core premises, even if it hasn’t formally admitted them.

Dhurandhar signals that a threshold has been crossed.

The old reflexes—moral equivalence, studied silence, fear of discomfort—no longer hold absolute sway.

The audience is ready to confront harsh asymmetries, uncomfortable motivations, and adversarial intent without filtering them through sanitizing language. That readiness itself is the shift.

Importantly, this does not mean the film radicalizes society. It does the opposite.

It normalizes clarity.

It makes it possible to discuss hard truths without hysteria and without euphemism. Once that happens, the cultural immune system recalibrates. Future debates, policies, and narratives are forced to start from a new baseline.

Comments ()